The new CD Poems to Songs: Hatchootucknee (Snapping Turtle) can be seen, at least in part, as a family affair – that is, if you don’t have any trouble with the “family” connection skipping past nine or ten generations. The disc’s origins run all the way back to the early 1800s, with an important Choctaw figure named Peter Pitchlynn, and then jumps to the present day, where one of his descendants, Tulsa’s Scott Hutchison, has co-produced and arranged the disc with another noted singer-songwriter, Tanya Maksood. (For a story about an earlier Maksood-Hutchison collaboration, see the August 2021 issue of Oklahoma Magazine.)

“Peter Pitchlynn had nine brothers and sisters, and I had heard we were related,” says Hutchison. “I researched it and found out it was true. I’m related to him through one of his brothers, William Pitchlynn.”

That, of course, makes Hutchison’s daughter Norah a relative of Pitchlynn’s as well. Poems to Songs, on which she and Maksood supply the vocals, marks Norah’s recording debut. So there’s another family link to the record, a connection that stretches back to 1830 and then skips almost a century to the Hutchisons.

It was in the early 1830s that Peter Pitchlynn moved West with some 100,000 other Native Americans to Indian Territory, taking the arduous journey that became known as the Trail of Tears. By that time, Pitchlynn had already shown the qualities that would lead to his ultimately becoming a Choctaw chief.

“He was half-Scottish and half-Choctaw, and he became an attorney,” Hutchison notes. “So, after all the treaties went down and they’d moved everyone here, he became the Principal Chief – to make sure the deal was kept.”

In addition to being a tribal leader for several decades, Pitchlynn was a poet. And all these years later, his poems are again seeing the light of day, with Hutchison and his collaborators setting three of them to music for the Poems to Songs collection.

It’s not the first time that the creations of his Choctaw ancestor have inspired Hutchison. Back in the mid- ’90s, Hutchison was on the West Coast with his fellow Tulsa musician Steve Pryor, who had a major-label deal at the time. Hutchison got the idea to use part of Pitchlynn’s poem “Jawbone” as the chorus of a song he and Pryor had begun to compose. “Jawbone,” in fact, became the title of that collaboration, and while they managed to get it recorded, it never got past the demo stage.

“It was pretty funky,” he recalls. “We did it with our publishers, but it just didn’t happen.”

According to Hutchison, Pitchlynn’s poem “Jawbone” was written in 1831 in “bitter-winter Arkansas,” while Pitchlynn was still on the Trail of Tears. And, indeed, in both the poem and its musical version, frustration, anger and anxiety bubble out. However, in the two other Pitchlynn contributions to Poems to Songs disc, his words are often gentle and pastoral, extolling the virtues of nature and the natural life.

“When you read some of that stuff in ‘Jawbone,’ like the term ‘hard times we do know,’ it’s using terminology that the blues or, later, Woody Guthrie used,” Hutchison says. “And then, in some of his other poems, he talks about nature, about the flowers and birds, and so he kind of had this rootsy, hippie vibe, too. He appreciated nature a lot.

“And then, in the poem ‘Take Me Home Again,’ he’s got a line that goes, ‘the world we live in is strange, strange.’ And I thought, ‘Whoa!’” Hutchison adds with a laugh.

Although the Pryor recording of “Jawbone” ended up not going anywhere, Hutchison never gave up on the idea of turning some of Pitchlynn’s poems into songs. He says he knew the time had finally come when he heard his daughter and Maksood singing together.

“My daughter was taking [voice] lessons from Tanya, and it came to my mind that their voices would blend into the kind of Joan Baez-meets-pioneer-days style that I’d want when I translated the poems into songs,” he explains. “Norah had grown up before my eyes, and Tanya was here, and one day I just went, ‘Whaaat?’ I felt like the time was right.”

Once he committed to doing the project, Hutchison began adding other players. The well-known Tulsa music figure Hank Charles came aboard to engineer and play bass, while flutes and drums were handled by Gareth Laffely, an award-winning young musician who goes by his first name only. Hutchison first encountered Gareth some eight years ago, when the latter was a teenaged recording artist; at the time, Hutchison was doing reviews of discs by Native Americans for a San Francisco-based newspaper.

“When I heard his record – he played bass, drums, guitar and everything – some of the tracks sounded like early Jethro Tull or Traffic,” he recalls. “It was really, really cool stuff. So when I wrote the review, I put that in.”

Hutchison’s writing about Gareth’s album drew the attention of the noted American Indian actor (and Tahlequah native) Wes Studi. Studi contacted Gareth, got his CDs and a year later, according to Hutchison, put the young musician on a spoken-word project he was recording – which in turn led to Gareth doing some work for producer-director George Lucas.

“I think he’s on The Mandalorian, doing the flutes in the background, and I know he does a lot of work out of Nashville,” Hutchison says. “I got in touch with him, and I sent him the tracks [from Poems to Songs]. You know how the Indian songs start and end with a drumbeat? I wanted to fade in like that, so you’re listening to this music and there you are in 1831, hearing this song on the wagon train. I was really glad about the way he did that.”

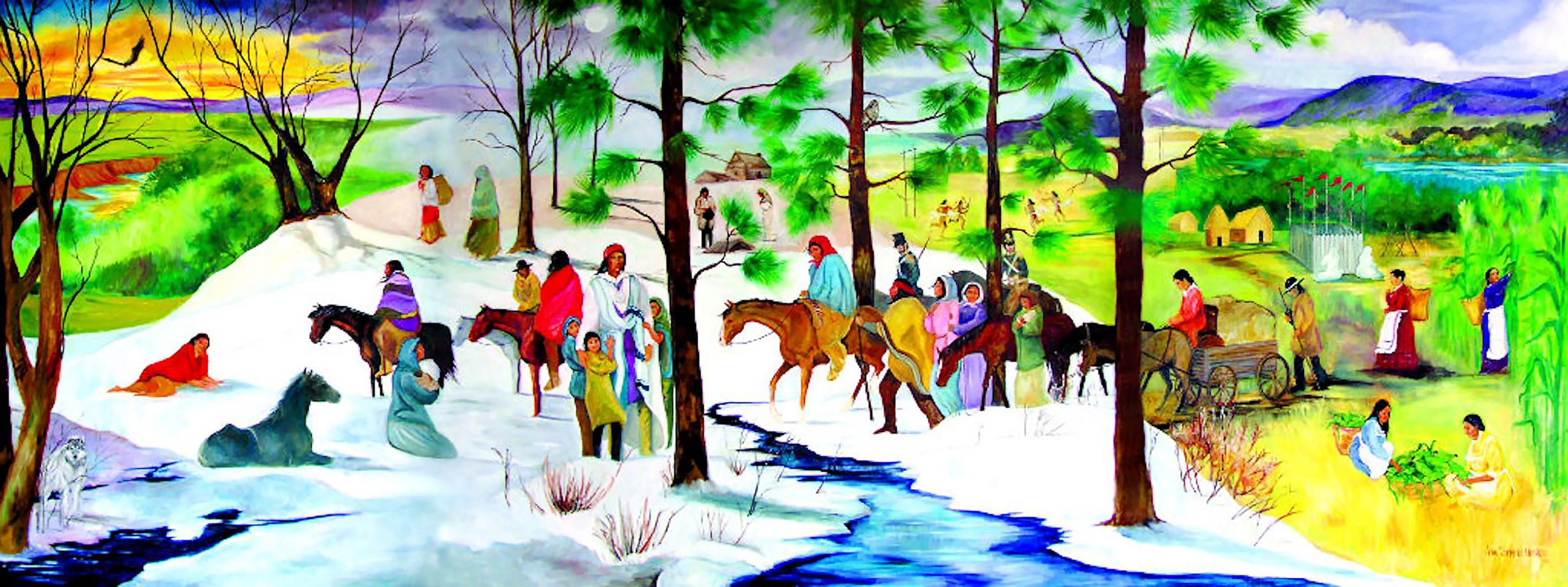

A final collaborator was artist J. Semple-Umstead, a descendant of two Choctaw chiefs (one of whom is Peter Pitchlynn, making her another part of the “family” angle). Hutchison had been impressed with a work of hers he’d seen reproduced on a Native American greeting card, and he contacted the Choctaw Nation headquarters, which put him in touch with her. The original Semple-Umstead piece seen on the cover of Poems to Songs is, notes Hutchison, “a mural at the Choctaw National Museum that’s 16 feet long and six feet high.”

Hutchison is quick to laud the Choctaw Nation for the help it’s given him with the project. He also points with pride to a letter he received from Charles Shadle – a noted classical composer and senior lecturer in music at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – who’s also Choctaw. After Hutchison sent him rough mixes of the three tracks on Poems to Songs, Shadle wrote, in part, “You and Tanya have done something truly remarkable with these songs. I think setting Pitchlynn’s poems in a style that evokes modern folk and country styles is right, especially as these styles harken back to the very sort of music that Pitchlynn and his people would have had in their ears … While your work is very different from my own, I recognize a gifted professional who is absolutely the master of his craft!”

For more information on Poems to Songs, visit the Peter Pitchlynn Poems to Songs, Hatchootucknee Facebook page. The disc is also available at the Pierson Gallery, 1313 E. 15th St. in Tulsa, and at the Choctaw Cultural Center in Durant.

Photo caption: Artist J. Semple-Umstead, a descendant of two Choctaw chiefs (one of whom is Peter Pitchlynn), created this mural at the Choctaw National Museum. The artwork also graces the cover of Poems to Songs. Photo courtesy John Wooley