Oklahoma wouldn’t be what it is today without the countless contributions of Black Americans. However, many of their stories are omitted from history textbooks. Celebrated every February, Black History Month aims to address this erasure, acting as a time to re-examine the past and celebrate the achievements of Black visionaries throughout history.

“As a historian, I have the fortune of studying these histories year-round,” shares Matthew Pearce, Ph.D., who serves as the State Historian at the Oklahoma Historical Society. “But I think it’s important that we commemorate Black History Month as a way to come together and acknowledge Black history and its importance to both Oklahoma and U.S. history.”

African American Settlement in Indian Territory

Oklahoma has a unique history of African American settlement. The Trail of Tears, which is known for its connection to the Five Tribes, is also the reason the first African Americans arrived in present-day Oklahoma.

Enslaved by the Five Tribes, Black Americans were forced to make the harsh journey along the Trail of Tears to Indian Territory with their slaveholders.

“We know a good deal about Native American history, but even that can sometimes not always be fully appreciated, especially the intersection of Native and Black history here,” reflects Raymond Doswell, Ed.D, a public historian, educator and the executive director at Greenwood Rising in Tulsa. “I think it’s something that visitors – and I’ll say for myself too – find surprising.”

During the Civil War, many enslaved people fought for the Union, forming four All-Black calvaries and infantries. Dubbed “Buffalo Soldiers,” these regiments represented 10% of the army’s effective strength and were pivotal in defeating the Confederacy.

The Rise of Oklahoma’s All-Black Towns

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, many Freedmen migrated from the Deep South to Indian Territory, participating in the Oklahoma Land Runs.

“It became an area where Black town promoters like E.P. McCabe pointed to Oklahoma territory as a potential haven for Black settlers,” explains Pearce.

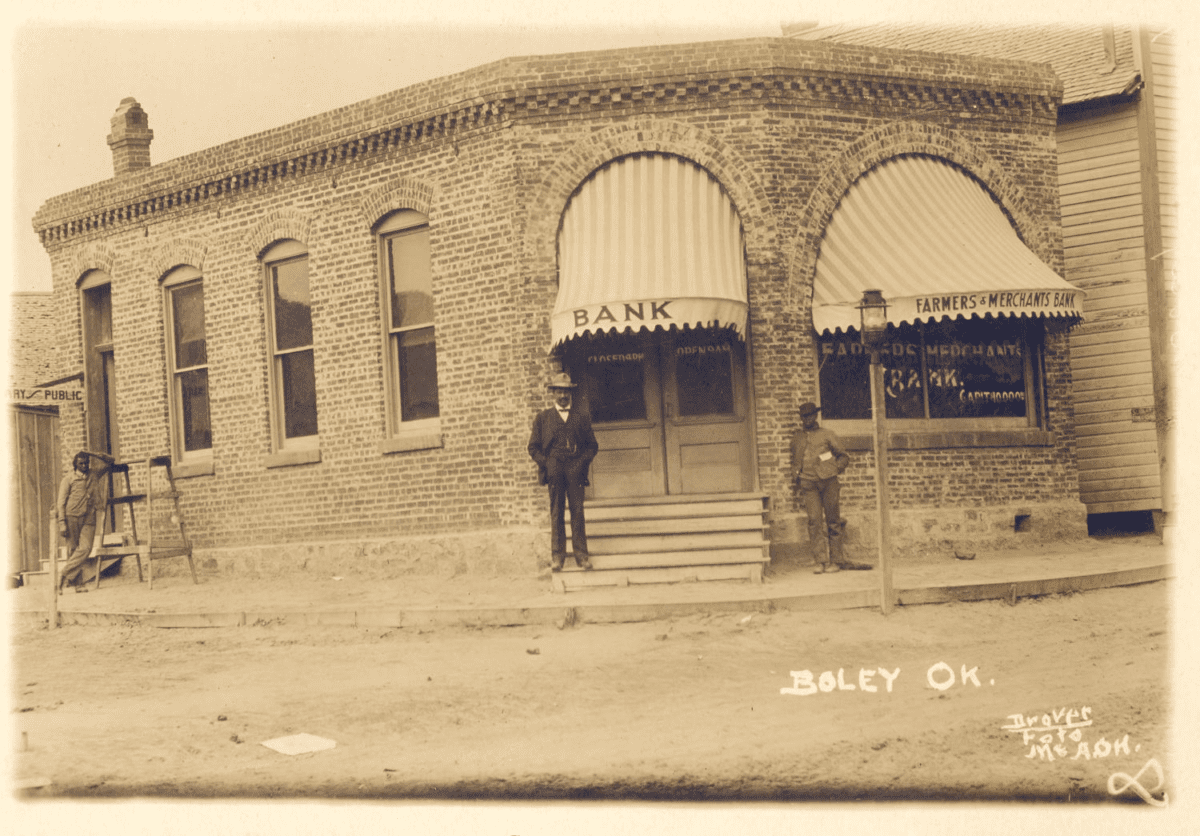

Between 1865 and 1920, more than 50 all-Black towns formed across the state. Among these towns, Boley was one of the largest, featuring a teeming business district with banks, cotton gins and a Grand Masonic Temple.

Boley also became the birthplace of the oldest all-Black rodeo in the United States. Founded in 1903, the Boley Rodeo continues every Memorial Day weekend, paying tribute to the town’s rich Black American roots.

Located in Oklahoma City, the Oklahoma History Center’s exhibit Realizing the Dream highlights the state’s African American history, including the rise and fall of Oklahoma’s All-Black towns, 11 of which still exist today.

Remembering the Rosenwald Schools

During the 20th century, nearly 200 educational institutions for Black schoolchildren were constructed across the state. These schools were made possible by the Rosenwald Fund, a philanthropic program that was established by Julius Rosenwald.

At least 11 of Oklahoma’s all-Black communities built schoolhouses through this program, including the Rosenwald Hall in Lima. Built in 1921, the Rosenwald Hall served as the community’s only elementary school for 45 years.

Now defunct, the school is one of the only Rosenwald institutions that still stands. In 1984, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and the community undertook efforts to raise $1.5 million to fully restore the school in 2023.

The Legacy of Dr. John Hope Franklin

The Rosenwald Fund also created fellowship grants for African American artists, scientists and scholars. Among its recipients was Oklahoman historian John Hope Franklin, Ph.D.

Born in 1915, Franklin was the son of E.B. Franklin, a survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Dedicated to education and public policy, Dr. John Hope Franklin worked as a member of the research team in the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v Board of Education.

In honor of his legacy, the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation was founded to promote reconciliation through community engagement and scholarly work. The center manages the John Hope Franklin Park in Tulsa, which serves as a memorial for remembering Oklahoma’s complex heritage.

In December, the nonprofit launched a capital campaign to raise funds for the construction of a new facility in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District. The facility will provide a permanent space for hosting exhibitions and community events that retell a fuller story of Oklahoma history. To learn more, check out jhfcenter.org/capitalcampaign.

Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District

Welcoming 40,000 visitors annually, Greenwood Rising is dedicated to educating the public about Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District. The award-winning museum accomplishes this by taking visitors on a narrative-driven, immersive experience that recounts the history of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street.”

“This is a history that many Oklahomans don’t know in spite of the fact that it happened in their home state… It’s quite eye-opening for them,” says Doswell.

To further drive awareness, the museum has partnered with the Tulsa Police Department and Tulsa Public Schools to educate both police cadets and all eighth-grade TPS students about the creation, destruction and lasting impact of Greenwood.

In celebration of its fifth anniversary, the museum will expand its community outreach and offer discounted admission to visitors on select days. To learn more, go to greenwoodrising.org.

“In a climate where we’re trying to homogenize history, it’s important to understand and realize the diversity of stories in our histories,” says Doswell. “It’s not a pretty history in some respects, but there are some triumphs in there as well, and we need to embrace it all.”

Featured photo credit: Members of the town council in Boley – an all-Black town in Oklahoma – pose for a photo in the early 1900s. All photos courtesy the Oklahoma Historical Society unless otherwise marked