Tribal Updates

Modoc Nation

Oklahoma’s larger tribes are reaching some major milestones in areas like economic development, education, healthcare and cultural preservation. But it’s important to note that smaller tribes are also prospering, says Modoc Nation Chief Robert Burkybile.

“We have a bit of an advantage as a small tribe,” says Burkybile, who leads the Nation of 355 citizens. “We have people who want to work and see this thing succeed. We want to open doors for tribal members in the future.”

One flourishing program is a 400-head bison ranch. Thanks to a federal grant, the tribe processes about four bison a month and distributes the meat to tribal members and non-natives in Miami and Ottawa County, where the tribe is based. Cuts of meat are delivered to schools, food banks, nonprofits and to neighboring tribes.

“It provides nutrition for the community,” Burkybile says.

The tribe is constructing a new building, Healing House, for outpatient behavioral health services for youth and adults. Modoc Nation Health Services also includes a treatment center for adults with substance abuse and mental health disorders; therapy for children with developmental disabilities; an equine therapy program; and a fully-equipped exercise center.

Choctaw Nation

Oklahoma Lt. Gov. Matt Pinnell praised the Choctaw Nation and all Oklahoma-based tribes during the May 23 grand opening of the Choctaw Landing Luxury Resort and Casino in Hochatown.

“You are leading the way in economic development,” Pinnell said. “Our tourism industry is the third-largest industry in the state because of our sovereign nations.”

Choctaw Chief Gary Batton mentions that the 100-room resort hotel created 400 jobs.

“There are more than 400 pieces of Native artwork on display throughout the resort,“ Batton says. “It’s a true cultural joy just to walk into the facility.”

James Grimsley is the executive director of advanced technology and initiatives for Emerging Aviation Technologies, a research facility located on more than 44,000 acres of land owned by the Choctaw Nation.

After more than 30 years of working in aviation research, “they made me an offer I couldn’t refuse,” says Grimsley, who also serves on the Oklahoma Transportation Commission. “I never thought I would have an opportunity on the reservation,” he says. “I grew up on the reservation, I know the culture.”

In October, the tribe broke ground near Redden on an Emerging Aviation Technology Center, which will be a hub for cutting-edge research on aerial system technologies. It’s one of ten sites chosen by the federal government for its Drone Integration Pilot Program. Much of the research focuses on the benefits of using drones in rural areas.

“If you live in Dallas and have a heart attack, an ambulance is four to seven minutes away, and usually they can save your life,” Grimsley says. “In southeast Oklahoma, it might be an hour or more away. Your zip code determines if you live or die.”

Lifesaving uses for drones may include sending an automated external defibrillator or an EpiPen to a rural residence, or transporting donor organs, Grimsley says.

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation broke ground in June for the $10 million Wilma P. Mankiller Cherokee Capitol Park.

“This project will not only transform unused land into a vibrant community space, but it also pays tribute to a remarkable leader who helped shape our tribe’s history as the first woman elected principal chief,” says Cherokee’s Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. The park is set to be completed in the fall of 2025.

In May, Oklahoma State University’s College of Osteopathic Medicine at the Cherokee Nation graduated its first-ever class of physicians. OSU-COM at Cherokee Nation, the nation’s only tribally affiliated medical school, is located in the Nation’s capital, Tahlequah. The 85,000-square-foot facility offers anatomy labs, a simulation center with computer programmable manikins, lecture halls, classrooms and a wellness center.

“I believe that this partnership will advance quality health care for all by allowing us to teach a new generation of medical professionals to serve our communities for years to come,” says Hoskin Jr. “I wish each and every student the best as they begin this journey. They have our full support.”

Chickasaw Nation

Chickasaw Nation Gov. Bill Anoatubby led groundbreaking ceremonies June 26 to kick off construction of the Chickasaw Heritage Center within the tribe’s historic homeland in Mississippi.

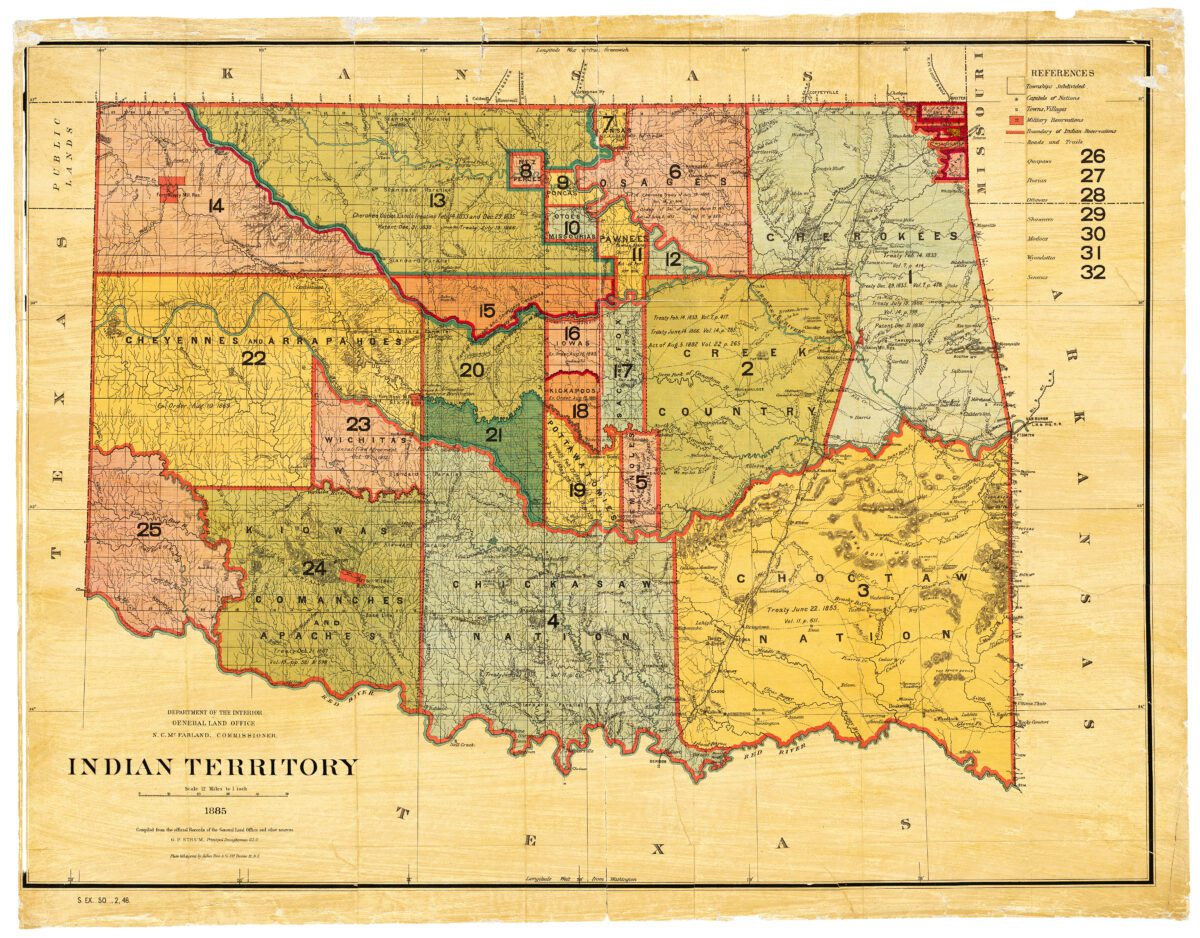

Visitors to the CHC, to be completed in 2026, can learn about the tribe’s history from prehistoric times to 1837, prior to the tribe’s forced removal to Indian Territory.

The 162-acre campus will contain an exhibit hall, theater, café, art gallery, administrative offices, gift shop and playground. Walking trails will connect the campus to the Natchez Trace Parkway’s National Scenic Trail under an agreement with the National Park Service.

A project of the Chickasaw Inkana Foundation, the center is a collaborative effort by the state of Mississippi; Tupelo Convention and Visitors Bureau; city of Tupelo; individual donors; and the Chickasaw Nation.

The Chickasaw Nation’s OKANA Resort & Indoor Waterpark is scheduled to open in 2025, adjacent to First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City. The $400 million resort will feature more than 400 rooms with riverfront and lagoon views, more than a dozen food and beverage outlets, a family entertainment center, a conference center and community programming including live music.

Muscogee Nation

Citizens of the Muscogee Nation can enjoy hunting and fishing in the treaty territories of other tribes participating in the Five Tribe Wildlife Management Reciprocity Agreement.

Tribal members and citizens of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee and Seminole nations will allow hunting and fishing licenses issued through each tribe to be recognized by the other tribes on their reservation land. Most tribes allow for tribal membership cards to serve as the license. The agreement reached in July will allow the Five Tribes to collaborate on wildlife management and enhance their ability to manage natural resources.

“Since time immemorial, our people have been the original environmentalists, looking to the land for sustenance and abundant life,” says Muscogee Nation Principal Chief David Hill. “I’m proud of this new agreement with the Five Tribes, as it not only shows a strengthening of our sovereign rights to hunt and fish on these lands, but gives us greater autonomy over the care and preservation of them for generations that follow.”

A mural project that is a partnership between the Muscogee Nation and Okemah Mainstreet was established to showcase the beauty and richness of Mvskoke art and culture to visitors to Okemah’s downtown, which is undergoing enhancements.

Muscogee artist Joe Hopkins, of Chandler, Ariz., was chosen to create the mural. Hopkins previously painted murals for the city of Eufaula and the Riverwalk in Jenks. Hopkins says his artwork is inspired by the living cultures of tribal nations, and he draws from the past to infuse his works with a fresh take on Indigenous life.

Activism & Getting Involved

Tribal citizens, as well as their leaders, should be involved in law-making decisions, and a good place to start is by voting in tribal elections, Choctaw Nation officials say. However, voter turnout for tribal elections is only at about 28%, says Candace Perkins, the tribe’s director of voter registration.

“We always like to preach: your vote is your voice,” Perkins says. “Your vote really matters.”

Efforts to increase participation include media advertising, reaching out to Choctaw citizens who live outside Oklahoma and upgrading to online voter registration, Perkins says.

Sarah Jane Smallwood-Cocke, the tribe’s senior government affairs strategist, is involved in relationship-building and partnerships between the tribe and local governments, including the 78 municipalities on the reservation. She also encourages tribal citizens to run for local, state and federal office, and to apply for appointments to boards and commissions. Smallwood-Cocke says she tries to set an example by serving on the city council in Wilburton.

“The goal of our department is to make sure the Choctaw have a seat at the table,” she says. “Our job is to help our tribal members engage at every level of government.”

Tye Baker, senior director of the tribe’s Environmental Protection Service, was appointed in June to the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. Kelbie Kennedy, an attorney, was hired in 2022 as the first-ever national tribal affairs advocate for the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Choctaw Chief Gary Batton represents the eastern Oklahoma region on Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s tribal advisory committee.

“We have to go to Washington, to make sure our voices are heard, to try to make policy changes,” says LaRenda Morgan, governmental affairs officer for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes. “We have to be activists on behalf of our own tribes.”

Buying back land historically owned by tribes is an important form of activism, says Cornel Pewewardy, an associate professor of political science at the University of Central Oklahoma. Pewewardy, who is Comanche, retired in 2017 from Portland State University, where he was director of the Indigenous Nations Studies Program. His research focuses on racial and socioeconomic inequities within Indigenous education. He helped write Senate Bill 429, which allows Native American students in Oklahoma to wear their tribal regalia during commencement ceremonies.

“We are always in pursuit of land,” says Pewewardy. “Land is a part of economic development, and with that you get to exercise your power in agreements with the state and the federal government.”

Tribal Scholars

Oklahoma Natives in the entertainment industry have been “having a moment,” what with the popularity of Sterlin Harjo’s Reservation Dogs television series and movies such as News of the World and Killers of the Flower Moon. Native American writers, artists and artisans are perennially celebrated for their work – and rightly so. But many who are not necessarily household names have distinguished themselves in other career fields, says James Parker Shield, director of the National Native American Hall of Fame (NNAHOF) based in Great Falls, Mont.

“We should always remember those who blazed a path for other Natives to follow, who made our lives better,” Shield says. “By making Indian Country better, they have made America better.”

Tresa Gouge, education coordinator for the NNAHOF, says one such trailblazer who comes to mind is Stephanie Burghart, executive director of Oklahoma Indian Legal Services.

“She is Kiowa,” Gouge says. “She provides assistance to low-income families and helps out with court services at all tribal courts in Oklahoma.”

Shield says many people have been mentored by the educators Henrietta Mann and the aforementioned Cornel Pewewardy.

“Henrietta Mann – we are inducting her into the hall of fame in October,” Shield says. “She’s been a highly regarded educator at the college level for many years. I’m sure she has a lot of proteges out there, people she has influenced and inspired to go into education.”

Mann, a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, is a professor of Native American Studies who has taught at the University of California at Berkeley, the University of Montana and Montana State University. She helped start Indian Studies programs at several universities and worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She received the National Humanities Medal in 2021.

Bailey Walker, a Chickasaw citizen, is president of the American Indian Chamber of Commerce Oklahoma. He is president/CEO of Four Winds Strategy Group and director of tribal relations for Tribal Diagnostics.

“He’s very engaged in the business world,” Shield said. “Through his leadership he’s able to help other Native businesses.”

Sovereignty

The legal profession is important to tribes and tribal citizens for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the concept of sovereignty.

“To me, sovereignty means autonomy, that you know who you are, that you do things that your people have always done,” says Pewewardy. “The more people there are who think that way, the more of a sovereign nation you become. I’m happy to see a lot of lawyers, a lot of new lawyers, at the forefront.”

The Oklahoma State University Center for Sovereign Nations, founded in 2015, collaborates with tribal nations to maintain government-to-government relationships with the United States as well as states and municipalities.

“Long before the United States became a country, Indigenous Peoples were independent and self-governing sovereigns. Because they are sovereigns, tribes still govern their own members and remaining territory,” the OSU program explains on its website.

Morgan, from the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, continues: “Every tribe has treaties that are living documents, that are still active today, but not always recognized by the government that created them. That’s where a lot of political issues begin, is with tribes not being able to exercise their sovereignty.”

Oklahoma City University announced in June the formation of the OCU Tribal Sovereignty Institute to be housed at its law school.

Osage Nation Principal Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear says that as a practicing attorney, he sees every day the prominence of sovereignty issues.

“We need information that is accessible to attorneys and policymakers and members of the public,” he says. “I think this institute can play a critical role in this regard, and I’m pleased to see it launch.”

Bridging the Gap

Many Oklahoma tribes have programs designed to address disparities in such areas as healthcare, education, child welfare and environmental protections.

When it comes to health disparities, “our big one is diabetes wellness,” says Morgan with the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes. The tribes offer classes in nutrition, fitness and other aspects of wellness and collaborate with Indian Health Services (IHS) dieticians.

“We often do weight loss challenges,” she continues. “We do health promotion events. We provide bison meat for people with diabetes, as well as eyeglasses.”

IHS, Moran says, “is providing tribal citizens as good a care as they would get elsewhere. I choose to go to IHS, because I believe they are targeted toward our diseases that are rampant.”

Pewewardy believes getting the right education is integral in bridging those noticeable gaps.

“The key to success is to get a diploma,” Pewewardy says. “We still have a high dropout rate. And the key to success in education is self-esteem.”

Boarding schools, Pewewardy says, “did not teach our people about who they are. They were ashamed to be Indigenous. So they tried their best to assimilate, but because of racism were not able to be equal.”

Native children who struggle in school “are being pushed into special education classes, and this causes a dilemma with their social skills. A lot of kids become hopeless about life. There’s still a high suicide rate among Natives,” Pewewardy continues.

Pewewardy, who spent three years as vice-chairman of the Comanche Nation, praises the creation of the Comanche Academy Charter School in Lawton. The mission of the free, accredited public school states in part that it “will nurture strong, compassionate bilingual young people who are committed to their personal and community health, wellness, relationships and progress.”

Tourism Draws

European visitors to Oklahoma “want to see what an Indian is,” Cheyenne and Arapaho Gov. Reggie Wassana says, and the state’s 39 tribes are working hard to tell their stories.

“Tourists across the state, the country and the world are very interested in learning more about First American people in an accurate, respectful way,” says Adrienne Lalli Hills, director of learning and community engagement at the OKC-based First Americans Museum (FAM). “People are realizing that it’s important that Native peoples are telling their own stories about themselves. We are doing that here at First Americans Museum. The majority of our staff are tribal citizens. That changes the way we think about educational programs, exhibits and public events. We have personal ties to the tribes.”

The museum offers exhibits and storytelling that depict all the tribes based in the state, but “many of our tribes do maintain their own cultural centers, libraries or some sort of visitor center,” Hills says. “And so we are careful to refer people to those sites as well.”

Hills says that it’s “so exciting to see people from all over the world come to First Americans Museum. It’s particularly exciting because we are telling our own stories on our turf.”

Visitors to FAM especially love the portion of the Oklahoma exhibition that addresses ancestral North America, Hills says.

“A lot of people do not realize that prior to European arrival, there were big cities here in North America that rivaled the size of European cities,” Hills says. “We had trade routes, we had music, we had sports, we had art and we had really sophisticated forms of

government.”