Unlike a lot of his fellow Oklahomans, drummer, composer and music teacher Jared Johnson didn’t encounter John Steinbeck’s masterwork, The Grapes of Wrath, during his high school or college years because he wasn’t assigned to read it.

He discovered it all on his own. Maybe that’s part of why it had such an effect on him.

“I was probably in my 20s when I first read it,” Johnson says. “I’d been doing a little bit of genealogy, trying to find out more about my roots. My people are all from Oklahoma and Arkansas, and my grandparents and great-grandparents were farmers and sharecroppers. I knew a little bit about the [novel’s] story. I knew it was an Oklahoma story. That’s what drew me to it.”

He chuckles.

“I had no idea what I was getting into,” the Muskogee resident says. “It ended up meaning so much to me on an emotional and spiritual level. There was something in that story, about the collective soul of man, that caused a spiritual epiphany in me, that really resonated with me. I was sort of navigating my way through spiritual things in my own life, and what Steinbeck was saying to me was profound. It was almost like, on that journey, I was building an altar [to Steinbeck’s words].”

Like Johnson, I first came to Steinbeck in my 20s after returning from overseas duty and enrolling, thanks to the G.I. Bill, in graduate school at what was then Central State University. Determined to make a living as a writer, I’d checked out the state’s colleges and found out that the Edmond school’s creative-writing program had a talented commercial author named Marilyn Harris offering classes. That sounded like what I needed.

I also realized I needed to get more familiar with some of the great American writers, which is why I bought a dog-eared copy of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row for a dime at a used bookstore in Edmond, along with similar volumes by F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner. It wasn’t long before Steinbeck had emerged as my hands-down favorite writer and I was busy reading any of his other books I could get my hands on, including The Grapes of Wrath.

I’m not sure how Johnson and I found out we shared a love of the same author, but I know our first conversation about Steinbeck happened in the early part of this decade, backstage (at the Cain’s Ballroom, I believe) before a show by the Tulsa Playboys. I was doing the announcing that night, he was drumming with the band, and we somehow learned that we both were crazy about Steinbeck’s novels.

What followed was an animated fanboy chat that continued even as the band took the stage. It would be the first of several for us.

I know that Steinbeck has had a major influence on my own writing, and that I’m hardly alone in that regard. But his impact on the arts goes well beyond authors and books – and even movies, including the classic version of Grapes by director John Ford. Woody Guthrie, for instance, was heavily influenced by The Grapes of Wrath, as is Bruce Springsteen. And, with his concert piece called The Grapes of Wrath Project, Johnson joined their ranks by creating his own musical testimonial to the enduring spirit of Steinbeck.

Although The Grapes of Wrath Project was first performed a few years ago, its seeds go back to Johnson’s college days at Northeastern State University, where he studied with renowned jazz instructor Joe Davis.

“Ed Thigpen, the great jazz drummer who played with Oscar Peterson, came and did a concert at NSU, and I was charged with giving him a ride to the airport,” Johnson says. “On the way up, we talked a lot about composition. He was a composer, and he was really encouraging me – ‘Man, you gotta write!’ – and that lit a fire under me.

“So, since college, I’ve always practiced composition and sketched out ideas. But I never felt that I wrote a completed thought – just ideas. So I had a few things in the drawer. Then, one night when I was getting ready to go to bed, I was thinking about Steinbeck, and it just kind of hit me like a flash: What if I wrote a piece based on one of the characters from The Grapes of Wrath?

“From there, it became this sequence of things that all had a cohesion. Once I had the idea, I was able to write with a purpose and have all these character references, if you will, as I was coming up with melodies and moods in the songs. The music had an ambition; all I’d needed was a muse.”

The result is what he terms “a suite of songs” – jazz instrumentals deeply influenced by the novel and featuring titles like “Land Turtle,” “All Men Got One Big Soul” and “Her Lips Came Together and Smiled Mysteriously.”

“It’s not a complete narrative,” Johnson says, “but it’s glimpses into the story. Thematic things from the general chapters, characters or quotes from the book became the titles to my songs. I don’t know that I’m doing the book justice in any way, but this is my take on it, through music, and I’m pretty happy with it.”

He’s also likes that top area musicians came aboard to help him get his vision across. They include trombonist Steve Ham, saxophonist Mike Cameron, pianist Scott McQuade and bassist Jim Loftin, along with mandolinist Isaac Eicher, who recently left Oklahoma for Nashville. Recruited for the The Grapes of Wrath band, dubbed Next of Kin, they’ve all worked with Johnson in various aggregations, jazz and otherwise, over the years.

“I play with Mike pretty regularly, and usually when I do Scott’s in on it, too,” he says. “I want to say that Mike and Scott and I have been playing together for maybe 10 years. And then I play with Ham and Isaac, when he’s available, in the Tulsa Playboys, which is a steady working group. Jim Loftin and I have played on and off together for over 20 years. He’s a dear friend, and we’ve worked together in every conceivable situation – rhythm and blues bands, church bands, and everything in between. He was the natural go-to for this just because we have so much history together and I really like the way he plays.

“It’s an all-star group, and I’m very humbled that everyone is so invested in the project.”

I have to add here that I’m also humbled to have been included in live presentations of this project by setting up the songs with snippets of narration from the book. Those were chosen by Johnson, and he knew what he was doing: When I first rehearsed my part, it took me three or four times to get through the words without choking up. As he has done with his compositions, Johnson has distilled the feeling and themes of this timeless, powerful novel in the Steinbeck lines he’s chosen to introduce his songs.

Taken together, the words and music reflect the blinding light The Grapes of Wrath has shed on social injustice. It’s a light that still shines in current times – and needs to.

“The book is so politically present, even today,” Johnson says. “And in a lot of ways, even though it’s wordless, this music is protest music.”

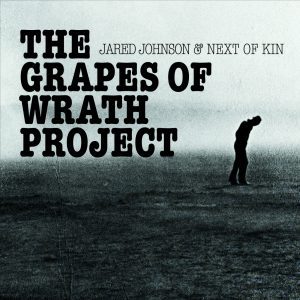

(The group recorded a CD of The Grapes of Wrath Project, minus the narration, in 2017. Johnson calls it an “abbreviated version, compressed for a recorded package.” It’s available from CD Baby, amazon.com, and other online outlets.)