Of all the filmmakers and actors I’ve known and/or interviewed over the years, few if any have been more fiercely dedicated to their art and craft than Oklahoma’s Clu Gulager, who died August 5 at the age of 93. For him, the art and the craft were the same thing; he based his work – and his life – on a two-word statement of purpose that he repeated to me several times over the course of our acquaintanceship: “Actors act.” It was his mantra, and it served him well.

Born William Martin Gulager in Holdenville, he was of Cherokee descent, getting his nickname “Clu” from the purple martins – called clu-clu birds in the Cherokee language – that lived around the family home. After growing up and graduating from high school in Muskogee, Gulager went off to the Marines and then to Northeastern State University in Tahlequah before transferring to Baylor, where he studied acting with his future wife, Miriam Byrd-Nethery. They married in 1952, and, three years later, they both made their television debuts in the then-popular CBS-TV anthology series Omnibus, doing an adaptation of a play they’d starred in at Baylor.

They remained husband and wife until Miriam’s 2003 death.

In a 1988 interview I did with Clu for the Texas-based magazine Movies Then and Now, he suggested that his national acting career came close to being over before it started.

“The director, Seymour Robbie, kept saying, ‘Clu, I like what you’re doing, but bring it down about 90%,’” he recalled. “‘Course, I knew he was dead wrong, because I had had so much success on the stage. People had laughed and patted me on the back after seeing my performance, so I knew that Seymour Robbie couldn’t possibly be right.”

He laughed.

“And naturally, I bombed … And I learned the hard way that when someone says bring it down, you’d better damn well consider it, at least when you’re working in front of a camera. There is a difference between working on the boards, trying to hit the 15th row, and working with a little tiny Sennheiser 416 microphone right here, six inches from your face.”

It was a lesson Gulager learned both quickly and well. Within a few years, he was a regular presence on episodic television, and, by 1960, he was the star of his own series, appearing as a sympathetic Billy the Kid in The Tall Man. After that came a recurring role in another ’60s TV western, the long-running Virginian, in which he played deputy sheriff Emmet Ryker.

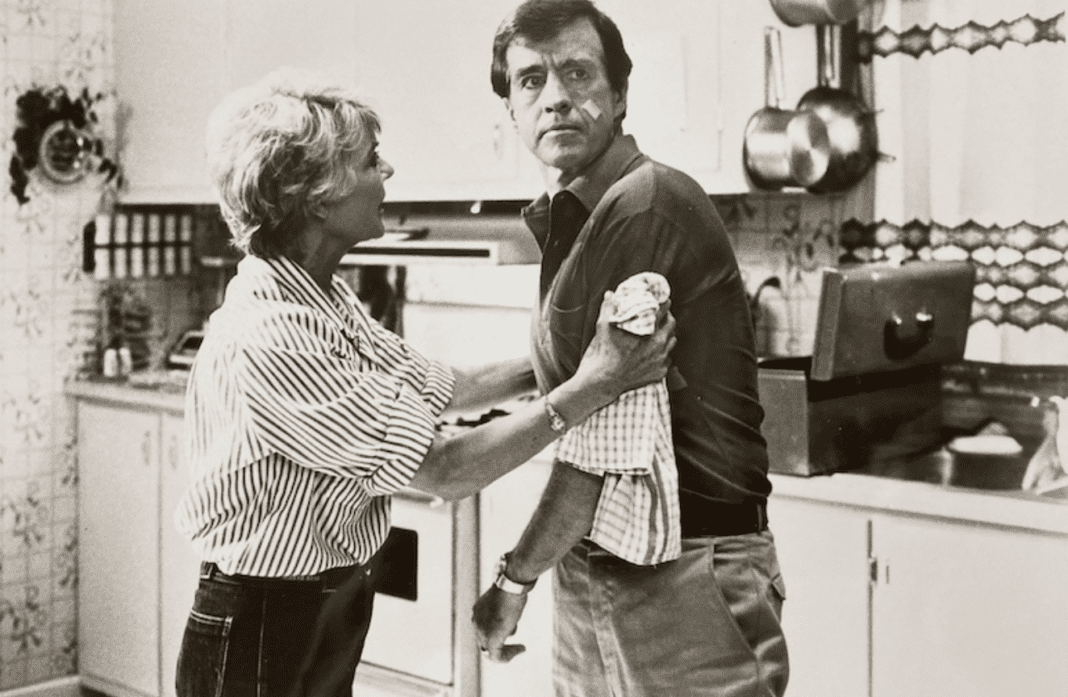

As far as feature films go, he’s probably best remembered for his hit-man portrayal (alongside Lee Marvin) in the 1964 version of The Killers and, seven years later, as the concupiscent character Abilene in The Last Picture Show. He does, however, have a sizable following from the horror movies he made in the latter part of his career, including such cult favorites as Return of the Living Dead and Nightmare on Elm Street 2 (both from 1985), The Hidden (1987), and the Feast trilogy, released between 2005 and 2009 and directed by his son John. A personal favorite of mine is his appearance in 1987’s The Offspring, when he and Miriam, playing a brother and sister, do a Southern Gothic turn that plays like something out of a Tennessee Williams fever-dream.

I remember talking to him several times about the horror genre, and hearing his observation that, as movie actors grow older, if they want to continue in the profession they’re going to have to do horror films. He would say this with not an ounce of bitterness or regret; rather, it was a simple statement of fact.

Perhaps there had been a time when Clu Gulager chased stardom; certainly, he had a long and serious flirtation with it, whether he coveted it or not. In a bonus interview for the 2006 DVD release of Vic, a harrowing short film in which he portrays a forgotten actor trying desperately to get back into the game, he touched on that aspect of his career in typical Gulager fashion, saying, “You set out to be as fine an actor as you can be, and you end up generally being a lesser commodity than you started out wanting to be. I was that. I didn’t set the world on fire, but I acted. And I was happy, and lucky and fortunate to be able to act professionally in American film and theatre during a very interesting time. I wasn’t an important part, but I wasn’t an insignificant part.

“And that’s what actors have to realize, probably. We mean something, but not everything.”

He brought so much intensity and pathos to that 30-minute movie, with his character spiraling downward into a sodden, hopeless heap by the end, that it’s exceedingly tough to watch. Knowing that it was the final film appearance of his wife – who’d passed away three years before Vic’s release – makes it even tougher.

Still, while he was stomach-churningly convincing in the role of a hopeless has-been, it’s good to remember that Clu Gulager’s real life was different. Although he’d been back on the West Coast for a couple of decades before he died, there was a time in the late ’80s when he and Miriam returned to Oklahoma, living in Tulsa for a few years, teaching acting classes even as Clu worked on his own feature film, which unfortunately remains incomplete. In our Movies Then and Now interview he laughingly told me that the reason he was teaching was “because I’ll always need money.

“American actors are not supposed to be teachers,” he added. “No professional actor who works a lot teaches, except me. I’m the only one in the nation who works all the time when I want to work and still teaches. So there are exceptions to everything.”

It was when they moved to Tulsa that I became acquainted with Clu and Miriam. I interviewed him several times for both the Tulsa World, where I was working at the time, and Fangoria, the horror-movie magazine. We did panels together, appeared at local conventions, and visited informally on several other occasions. I found him to be open and honest and completely devoted to acting and filmmaking, devoid of pretension, friendly and funny and eccentric in a very engaging way.

In 1990, he and Miriam both appeared in a made-for-TV movie I wrote called Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective, which director Chris Lewis shot mostly at Tulsa locations, including Bell’s Amusement Park. I was very proud to have them both in my little picture, but for all of that, my best memory of the Gulagers is a personal one.

Not long after they’d come to town, I was having a signing at the Tulsa Press Club for one of the horror novels Ron Wolfe and I had written. During the proceedings, I happened to look up and see Clu and Miriam coming through the door. To this day, I have no idea how they heard about the event, but there they were, and they went right over, bought a book, and brought it to me to sign.

At that point, I may have interviewed him once or twice, but I couldn’t say that I knew him. I was a bit stunned that this movie and TV heavyweight would go to the trouble of showing up and buy my little paperback. So I told him pretty much that, adding my thanks.

I’ll never forget his response.

“John,” he said, “we artists have to support one another.”

He obviously meant it. And from that day forward, I was one of the biggest Clu Gulager fans on the planet.