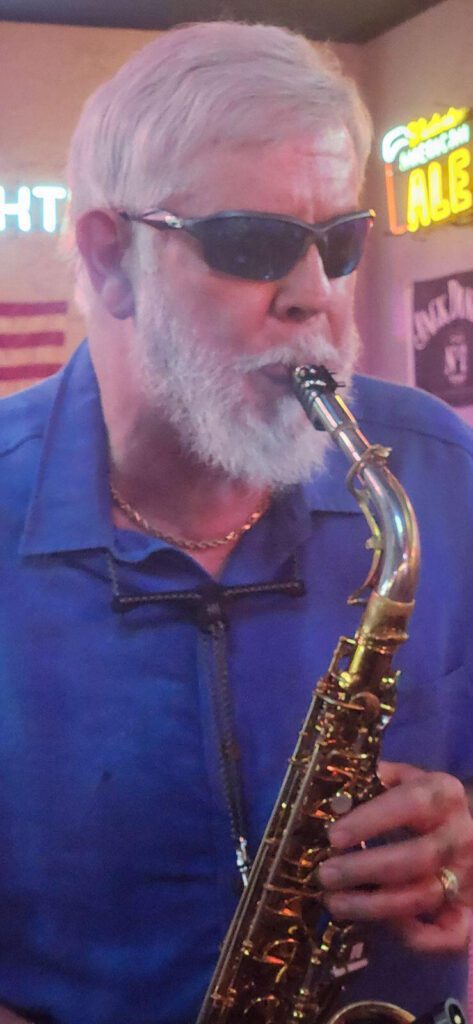

When it comes to star-studded musical resumes, Steve Wilkerson’s is a tough one to top. A professional saxophonist since the age of 11, when he joined his dad’s Bartlesville-based dance band, and a graduate of the University of Tulsa’s school of music, Wilkerson went on to work in the West Coast music scene for more than a quarter of a century. Even a glance at his credits during that time gives an idea of the depth of his involvement: Michael Bolton, Barbra Streisand and Barry Manilow jump out at you, but so do the likes of Mel Torme, Tony Bennett and The Temptations. They are among the dozens of major names with whom Wilkerson toured, recorded and/or performed.

Yet for all of the starpower that illuminates Wilkerson’s career, the entity who’s had perhaps the biggest influence on his life is someone he doesn’t even know by name. Their meeting didn’t happen on any of the thousands of stages Wilkerson’s played on, or in one of the many recording studios where he’s laid down tracks for his own discs and others, but in a third-floor room next to the nurses’ station at Tulsa’s Hillcrest Medical Center. And the encounter wasn’t only life-changing, but life-saving as well.

It happened a couple of years ago. By that time, Wilkerson and his wife – the noted vocalist, guitarist and arranger Andrea Baker – had been back in Tulsa for some time, more or less retired from the business. Then, one morning while Wilkerson was making coffee and checking emails, he suddenly realized that he suddenly couldn’t read the words on his screen.

“They looked like hieroglyphics,” he remembers. “My wife was on the phone with a friend of hers from Michigan, and Andrea told her, ‘Steve can’t read his email.’”

“Her friend had lost her husband to a stroke, and she said, ‘He’s having a stroke. Get him to the hospital now.’”

Enlisting the help of their son, who lived nearby, Baker got Wilkerson to a Claremore hospital, and from there to the Stroke Center at Hillcrest in Tulsa.

“Hillcrest was great,” he says. “They had a neurologist waiting, and they got me in bed, and they said, ‘Well, we’ve got you on blood thinners. We’re just going to have to see what happens.’ But they were giving me a look that made me think, ‘Oh, man, maybe this is it.’

“That night, I realized the severity of the situation. They were waiting for another one to hit and just take me out. So I started praying, and I thanked God for everything in my life, for Andrea, for the people I’d played with, for the career I’d had. I said I really appreciated everything, and I guessed I was ready to come home now.”

Then, as he remembers it, he was trying to rest when “a weird gold light” started flashing on the wall by his bed, “like a kaleidoscope.” He figured it was the reflection of headlights in the parking lot, but when he looked out the window, everything was dark and quiet.

That was about 3:30 a.m., Wilkerson remembers. And he’ll never forget what happened next.

“Suddenly, in the room, here’s this guy, just standing there and looking at me. You know, when people look at you, their eyes move, but his didn’t. There was no vertical movement to them at all. He reached out like he was going to shake hands with me, but instead, he grabbed my wrist, and I went over like George Foreman had hit me. When I got up, no one was there.”

Then, Wilkerson went to sleep. And when he awakened, he says, “I felt incredible. All the anxiety, everything, was gone. They came in to check on me, and the guy said, ‘You seem to act like nothing has happened.’ He had obviously been looking at my MRI’s.

“I said, ‘I haven’t felt this good in 27 years. I’d like to get out and take a walk if that’s okay.’

Wilkerson laughs.

“He sent the head of the stroke center in, and they couldn’t figure out why I was coming back after something like this, with no slurred speech or anything. They checked my face and all that, and the doctor said, ‘I think we just got lucky with you. I don’t think it’s your time. Maybe God wants you to keep playing the saxophone.’

“Not too long after that, I was in Eureka Springs, talking to this lady about my stroke and what had happened, and she told me, ‘Well, you sent a prayer of gratitude up. And you were spared. You encountered an angel on the third floor.’”

Three days after Wilkerson was admitted to Hillcrest, Baker took him home. Once there, he knew he had to find out what the stroke had done to his musical ability.

“I called my son and said, ‘Well, I’m getting ready to play. Send up a prayer, because this is going to be it.’ I started playing, and I played so fast and with such clarity – I was able to play things I’d never been able to play before. I thought, ‘Where did that come from?’ It was just bizarre.

“So now,” he says, “I’m playing my horn because I realize I’m supposed to continue doing that.”

While Andrea – who has her own very impressive resume – has been able to gear down and enjoy retirement, Wilkerson has once again been seeking gigs. With his credentials, it hasn’t been hard for him to find work. In fact, it often finds him.

“I’ve gotten some calls for the Symphony, and for some jazz things, and then I started getting calls from some rock ‘n’ rollers,” he explains. “David Thayer, a wonderful guitarist here in Tulsa, called me up and said, ‘Hey, would you like to come out and play in my band?’

“I thought, ‘You know, this late in the game, I’d really like to do that.’ So I started playing the second Sunday and the last Sunday of every month at Four Aces on 41st and Garnett. It’s an afternoon gig, 2 p.m. until 5:30, and it’s been so much fun. I mean, nobody’s asleep on the bandstand. There’s a lot of intensity. I brought in what I had, and it really affected Steve Pounds, who’s a wonderful drummer. He said, ‘Man, when you start playing, I float. I can feel it.’

“We’ve got Bruce Dunlap on bass, a really cool guy, and boy, we just take it to another level. Bill Taylor, who plays violin, is another wonderful guy. He and I are like the string and orchestral section. When David sings ‘Wichita Lineman,’ we play together, and the way we’ve got it miked, it’s incredible. David says, ‘It’s like I’ve got my own orchestra behind me.’

“So I’m having fun, playing with some of Oklahoma’s finest musicians,” he concludes. “We’re having a big time. I’m able to get into the David Sanborn style of playing. And Edgar Winter. I just got an Edgar Winter mouthpiece for my saxophone.”

In addition to his regular appearances with Thayer’s group, he’s also preparing to go into the studio with songwriter-guitarist Raymond Berry, who recently put together an all-star lineup of Tulsa musicians to record his composition “Swing into Cain’s.”

“Raymond’s going to bring me in on some of the tunes he’s doing, to add saxophone tracks and maybe some flute as well,” Wilkerson says. “So I’m looking forward to that, too. You know, man, I’m getting really busy.”

Clearly, he sees that as a good thing.

“Over at Four Aces,” he says, “I’ve had people come up to me who are almost in tears, saying, ‘Thank you. What you just played – you have no idea what it’s doing for me.” And I think, ‘Wow. I guess I’m doing some good for somebody.’”