[dropcap]I’ve[/dropcap] known Billy Parker for maybe 30 years now. I’ve been around him in all sorts of situations, and I’ve watched what he usually does when someone starts telling him what a big deal he is.

“When I was a kid,” he’ll say, “my dad told me to stick my hand in a bucket of water. Then he told me to take it out.

“‘See that?’ he said. ‘You didn’t leave no impression at all.’”

I suspect that piece of folk wisdom had a profound effect on young Billy. It may go a long way toward explaining his humility, which is so sincere that those who only know him from his public persona figure it has to be an act.

Many years ago, I was one of those people. My new wife and I had just left the Oklahoma City area, where I’d been teaching English and American Literature at what is now Rose State College. We’d moved to Rogers County, where I grew up, with a plan for me to live in the country and write for a living. It ‘soon became evident, however, that I was going to have to do something to supplement my writing income – which, as the great novelist Raymond Chandler put it in one of his Philip Marlowe detective novels, was busy trying to crawl under a duck.

So, I became a disc jockey on KWPR, a 1,000-watt station out of Claremore that had recently been taken over by a family from New Mexico named Warren. Their assumption of ownership coincided with the rise of the rock ‘n’ roll- and pop-influenced dancehall country made popular by the 1980 film Urban Cowboy, a circumstance reflected in our playlists. The records we spun were country, country-pop, and country-rock. And, as “The Voice of the Will Rogers Metroplex” (our tagline), we were carving out a pretty nice little niche for ourselves.

We were not, however, the 50,000-watt country-music flamethrower KVOO, which lay about 30 miles down the highway from us and less than a tweak down the AM dial – from KVOO’s 1170 to KWPR’s 1270.

KVOO was exactly what its call letters stood for: the Voice of Oklahoma. Because of the way radio patterns worked in those days, it was actually the voice of much of the country beyond Oklahoma as well, covering a big swath of America with its powerful signal. Legendary for being the station that popularized a new and vibrant musical amalgam known as western swing back in the 1930s, thanks to the daily broadcasts of Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, KVOO had also been home, early in their careers, to the likes of western-movie superstar Gene Autry and radio icon Paul Harvey.

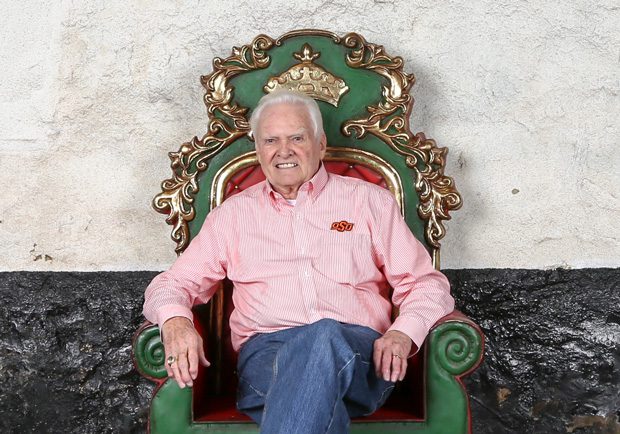

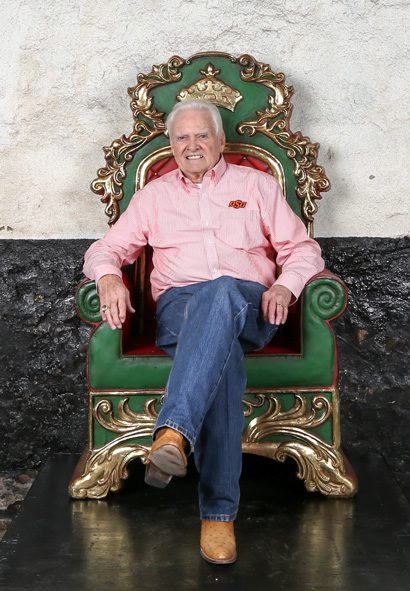

While I was at KWPR, KVOO had several terrific deejays on its payroll. But the undisputed star was Billy Parker. A former front man for Ernest Tubb’s Texas Troubadours, Billy continued to play and record successfully even as he held down a top-rated overnight show that would bring him multiple Disc Jockey of the Year awards from both the Academy of Country Music and the Country Music Association. If you lived around Tulsa in the 1980s, you at the least knew who Billy Parker was and what he stood for, not the least of which were the endearing country-star qualities of public humility and gratitude.

One day, KWPR’s station manager, Mike Warren, came back from some sort of a radio meeting in Tulsa singing Billy’s praises. “What a great guy,” he told me. “We had a really good visit. And you know, John, he treated me like an equal.”

Since Billy’s latest single, a spot-on evocation of honky-tonk ambience called “(Who’s Gonna Sing) The Last Country Song,” was then rising on the national charts (his 13th song to do so), and his station had 50 times the power of ours, I figured Billy was just being nice.

Later, I found out I was mistaken.

After having moved to the country to write, I instead found full-time employment as a writer 50 miles away in downtown Tulsa. For the next 23 years, I’d make the 100-mile drive daily and sometimes on weekends, doing entertainment-related stories and interviews for the Tulsa World. Of course, that gig brought me in touch with Billy Parker, and we got to know one another. It didn’t take me long to realize that Billy was one of the most sincere and self-effacing guys I’d ever met. He was not a phony. He was not too good to be true. He was a good man, and that was the truth.

We shared a love for western-swing music, and one day when I was at the station interviewing him for a story, he asked me to come into the studio with him and spin some swing records. After about the third song, and without consulting me, Billy said, “Well, folks, if you’d like to hear John and me do some of this western-swing music once a week, why don’t you give us a call and let us know?”

As I remember it, in the next five or ten minutes we had something like 80 calls. And so the program Wooley Wednesday was born.

It sure was fun while it lasted. Once, the veteran saxophonist Glenn “Blub” Rhees called in from his hospital bed to let our listeners know he’d been sick but that he planned to be on hand for the upcoming Bob Wills birthday celebration at the Cain’s Ballroom. Then he proceeded to relate a common but messy lower-intestinal problem he’d had for the past nine days.

There were no tape delays, so his non-euphemistic description went out over the air. It was followed by a live spot for Roy & Candy’s Music with Roy Ferguson, himself a musician who’d worked extensively with Glenn.

Billy and I were already having problems keeping our composure; we lost it completely after the first sentence that came out of Roy’s mouth: “Kinda sounds like ol’ Blub needs some cheese, don’t it?”

Another time, one of our older listeners was having a big wedding anniversary and asked us to play Marty Robbins’ “My Woman, My Woman, My Wife” and dedicate it to his spouse from him. We got out a Robbins’ greatest-hits LP and cued up the disc – unfortunately, one cut away from where it should’ve been – and over the airwaves rang another Robbins hit, “Devil Woman.”

Billy and I complemented one another. He was the guy who’d actually done it, touring and sharing stages with the likes of Bob and Johnnie Lee Wills and many, many others. I was the four-eyed writer with the grad-student perspective. The show worked because of our love for the music and, by that time, our love for one another. We managed to keep Wooley Wednesday going through a couple of ownership changes, but finally, like all things, our on-air partnership had to end. I’m happy to say that we have remained great pals to this day.

Once again, I’ve buried the lead in this column; in fact, I’ve saved it until the end. I probably should’ve started by telling you that Billy Parker retired from broadcasting in December, a fact that was the original catalyst for this piece. On the other hand, there will never be a time when Billy Parker won’t deserve to have something written about him, so it really doesn’t make any difference why I’m doing it now. In a time when the radio business is overrun with Lilliputians, my friend Billy will always and forever remain a gentle, genial giant. I’m proud to be able to write these few words about him.