Whether it’s moving into a new building, maintaining the school grounds or just nurturing strong student-teacher-parent relationships, the story is the same for two highly ranked Oklahoma charter schools: Success comes from mutual involvement by the entire school community.

Charter schools have been part of Oklahoma public education since 1999. Amendments to the Oklahoma Charter Schools Act in 2015 brought additional oversight by giving authorizing institutions, such as a school district, the tools to hold charter schools accountable, according to the Oklahoma Department of Education.

Oklahoma’s 30-plus charter schools are no-tuition public schools that operate under state educational guidelines but with more autonomy than conventional public schools. They are not allowed to issue bonds, and receive 75 percent of the state aid that public schools receive.

In return, says Steven Stefanick, principal of Harding Charter Preparatory High School in Oklahoma City, charter schools have more freedom than their traditional counterparts to find innovative ways to teach.

Stefanick says his school, which received an A rating from the Oklahoma Department of Education, compensates for the funding deficit “with creativity, more autonomy and parental involvement.” He cites Harding’s move this school year from its original home north of downtown OKC into a high school that was abandoned as part of an Oklahoma City Public Schools reorganization.

“We had one month to move in,” Stefanick says. “We had 100 parents, teachers and students [helping]. It cost us virtually no money to move.”

Harding now sits on a 50-acre campus, and Stefanick says parents have kept the grounds mowed during growing seasons.

About 460 students attend Harding, but “our capacity is 600, so we can grow,” he says.

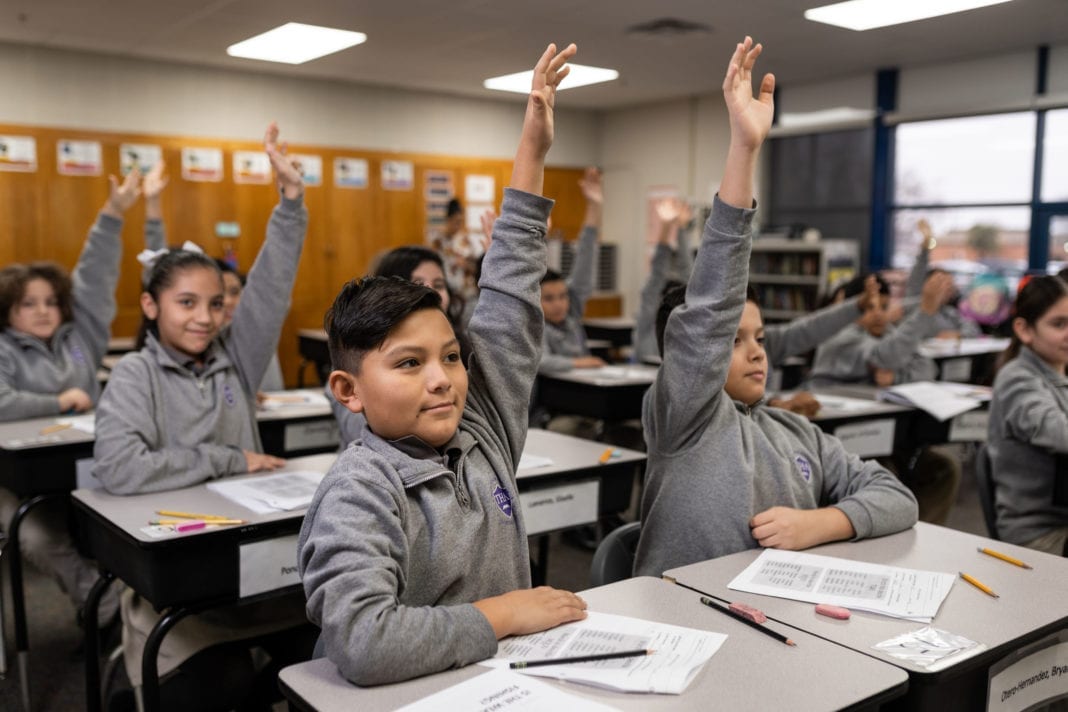

Elsie Urueta Pollock, founder and executive director of Tulsa Honor Academy, says the east Tulsa middle school has benefited from the commitments of parents and faculty. In August, the school began a ninth grade class and will add an additional grade each of the next three years to form a complete high school, she says.

“When we decided to add the high school, we got over 5,000 signatures of support in just 10 days,” says Pollack, whose school also received an A from the state education department.

Pollock says research shows only 6.5% of adults in the school’s target area for students have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

“It was not because they weren’t smart enough,” she says. “They were not being properly prepared for college. The school’s goal is to get all students into college.”

Tulsa Honor Academy’s enrollment is bilingual, with about 70 percent of its 520 students speaking Spanish at home, says Pollock, adding that the school has families volunteering to serve as translators at the school.

“This is a very special community,” she says.

Before this school year began, more than 200 volunteers contributed more than 1,000 hours of labor to get the academy moved into an unused Tulsa Public Schools elementary school.

“It shows the passion they have for this school,” Pollack says, adding that Tulsa Honor Academy is at capacity this school year with 520 students but is poised to grow with the addition of the high school grades.

“We have a long wait list,” she says.