When George Washington Miller (“G.W.”) first saw the tall bluestem grass and wild rye spread across northeastern Oklahoma in 1879, he didn’t just see prairie country. He saw raw possibility, an opportunity to build an empire inspired by the legends and myths he dragged from his Kentucky home. This, he realized, was the Wild West, and he and his sons would be its greatest evangelists, building nothing less than a church devoted to their sacred vision of the American frontier and its pioneers. They were imagineers before their time.

G.W. and his sons – Joseph, George Jr. and Zack – parceled together 110,000 acres of Indian Territory land leased from the Ponca, Quapaw and Cherokee tribes and started construction of the 101 Ranch in 1893. Only a few miles from present-day Ponca City, it would grow to become the largest diversified ranch in American history. It also would grow into a self-sufficient colony of sorts and the operational headquarters of the 101 Ranch Wild West Show, a vehicle for spreading the religion of the Wild West across America and later to Europe.

Many tales are told about the origins of the 101’s name, but ultimately, the origin of the name is unimportant. It derives its significance as a moniker for not just a working ranch, but as a focal point for the spread of Wild West mythology. “101” became synonymous with entrepreneurial success and the free-roaming, open air, rough-and-tumble lifestyle of American cowboys.

It Started With Bacon

“The history of the 101 Ranch is worth preserving for lots of reasons. At one time, it was the largest diversified ranch in America. It had the largest herd of buffalo in America. It was the birthplace of the 101 Ranch Wild West Show. The list goes on,” says Joe Glaser, secretary of the 101 Ranch Old Timers Association.

The fortune that enabled the building of his dream came from G.W.’s early investment in cattle. G.W. traded a load of bacon to a Texas rancher for cattle. What was left of the bacon was traded to Ponca Indians for leases on several thousand acres of land near modern day Ponca City. He brought cattle up from Texas and sold them in Kansas and Oklahoma markets.

The original lease served him well as a cattle run. In later years, the 101 added diversified farmlands to its offerings. Crops included wheat, cotton, corn, alfalfa and a variety of vegetables. The ranch diversified as well, providing cattle, bison, hogs, poultry and horses.

Living the cowboy life fueled G.W.’s passion for the Wild West lifestyle. He supervised the cattle drives himself. It was a rugged but completely free way to live, and he loved it. So did his ranchers. It was certainly no way to get rich, but many stayed on with the 101 – even when paychecks were sparse – because they, too, loved the lifestyle.

In 1903, G.W. died of pneumonia, passing away before seeing his dream fully realized. His sons, however, were just as passionate about the dream as their father was. By the time the 101 fell into their hands, it was an enterprise bringing in hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, an absurd amount of money at the time. And absurd amounts of money can bank big dreams.

Many products were hard to come by on the periphery of the frontier. Hard cash was no easier to find than the goods required to operate an endeavor as large as the 101, so the ranch printed its own script, exchangeable for goods and services available on the ranch.

For the most part, the Miller Brothers were clever entrepreneurs, and they independently provided the goods needed to keep the ranch running. At its peak, the 101 boasted a general store, school, cafe, hotel, smithy, leather and saddle shop, dairy, meat-packing plant, a power plant and, later, its own oil refinery. Hundreds of telephone wires kept the various operations of the 101 in touch with each other. But when entrepreneurial methods failed, the brothers weren’t afraid to gun up to make things go their way.

“They broke the laws when they felt like they had to. When somebody got in their way, they – shall I say – moved them out of the way, with whatever means it took. Sometimes it could be lethal,” says historian Michael Wallis, author of The Real Wild West: The 101 Ranch and the Creation of the American West.

Figures differ, but it’s fair to say that during its heyday the 101 employed 3,000 workers. Those workers were informed about the happenings on the ranch, as well as occasional news from the outside world, in the Ranch’s own newspaper, the Bliss Breeze. The 101 was a self-sufficient frontier colony.

Showtime

The year 1905 witnessed the origin of what later came to be known as the 101 Wild West Show. It sprang from the Millers’ newly adopted civic duty of advocating for Oklahoma statehood. The show opened that year to an audience of the National Editors Association plus 60,000 other spectators.

It was a bona fide crowd-pleaser, so the Millers took it on a national tour in 1907. However, the show wasn’t as successful as the Millers had hoped. By the time they ventured into show business, audiences already had their pick of fairs and at least a dozen similar shows, including the legendary Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

The show did serve to feed the global obsession with the Wild West mythology, though, and a number of its performers became celebrities.

“I believe the ranch represented the ‘spirit’ of America, both to the eastern United States and to the rest of the world. Here was a land endowed with an abundance of natural wealth and also the freedom and space to allow dedicated human enterprise to produce great individual wealth,” says University of Oklahoma history professor Linda Reese.

The first performance of the 101 show featured the Apache leader Geronimo, then a prisoner of war at Fort Sill. At the time of his capture, the American public and the federal government regarded Geronimo as nothing less than a terrorist.

Authorities released him from time to time under the recognizance of show and fair owners. Predictably, he performed stunts such as taking down buffalo at long distances from a moving car. He was also permitted to sell souvenirs at the shows to earn a little money. With the help of shows like the 101, Geronimo shed his notoriety in the eyes of the public and became a hero of sorts.

Bill Pickett was another popular performer in the 101 show. He was the first performing African-American cowboy. His own show, The Pickett Brothers Bronco Busters and Rough Riders Association, born in the 1890s, garnered acclaim and established him as a circuit star. Glad to give up management, he joined the nascent 101 Wild West Show in 1905, mesmerizing crowds with his unique talent for bull wrestling. Not all crowds witnessed his performances, though. America was deeply segregated, and Pickett was forbidden to perform in many towns and cities. Today, his grave on the 101’s Cowboy Hill is one of only a handful of reminders of Pickett’s show.

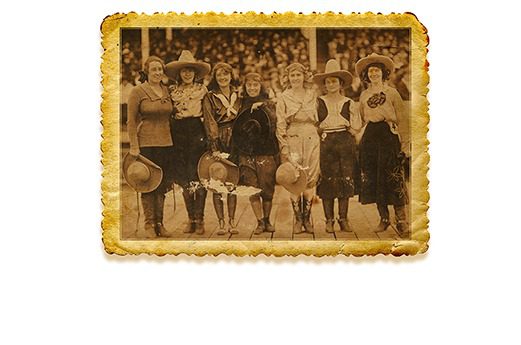

By the time the 101 Wild West Show began its national tours, there wasn’t anything new about female performers. There was something new about women that could ride and shoot, though. Lillian Smith, capable of doing both well, gained fame as the hated rival of the legendary Annie Oakley. She initially performed with Oakley in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows. Their ongoing feud was fodder for national coverage, but after a particularly ugly quarrel, Smith left Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and found a new home with the Miller brothers.

Smith performed as a ridiculously exaggerated character called, “Princess Wenona of the Sioux.” Over the next decade, she proved herself a better shot than Oakley but never approached Oakley in popularity and fame. After leaving the show, her star fell. In 1930, she died broke and forgotten in Ponca City.

Of all the performers in the 101 Wild West Show, Tom Mix merits special mention. As a kid, Mix dreamed of joining the circus. He spent his childhood mastering horseback riding, knife throwing, shooting and other “western” avocations. He joined the show in 1906, becoming one of its main attractions and leaving his audiences with the impression that he was a true cowboy. He attracted the attention of a burgeoning Hollywood, a film industry unsure of what it wanted to be but knowing the good stuff when it came along.

Mix’s first film, Ranch Life in the Great Southwest, gained immediate acclaim. He was wildly charismatic, embodying everything western in his films. Audiences couldn’t get enough. As America embraced the new medium and theaters sprang up around the country, Mix’s fame grew. Mix inspired Hollywood’s devotion to the western genre, a film niche that endured for five decades.

All told, Mix made 300 westerns. He became, like the Miller brothers but on a much larger scale, an evangelist of the Wild West lifestyle. During his long career, he took on another apostle of the Wild West – a young John Wayne, an actor who eventually surpassed Mix in popularity.

Bad luck, however, plagued the 101 Wild West Show during its entire run. In its first year on the road, a railroad accident and a case of typhoid fever that put the cast out of commission dipped the show into the red.

In 1908, facing intense competition from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows, Zack Miller took the show on a European tour. With the growing threat of war in Europe, the British government confiscated the show’s horses for military use. In Germany, some Lakota Sioux cast members were arrested under government suspicion as spies. Fleeing Europe presented itself as the best answer to the show’s growing problems, but Zack struggled to find a ship that would take the Native American members on board. Once they finally did make it home, Joe Miller caused every Native American member of the cast to desert the show when he refused to compensate them for overtime.

The show took a long hiatus while World War I raged. After the armistice, Joe worked hard to resuscitate the show, but to no avail. By 1927, it was clear that the show didn’t have a place in the post-war world, a world embracing movies, and he reluctantly shut it down. Not long after, Joe passed away, and with him went the last interest in the 101’s contribution to the entertainment industry.

The Beginning of the End

“The three brothers carried out the vision of keeping the image of the so-called ‘Wild West’ alive,” says Wallis. “I think of them, in simple terms, as three little boys. Part of them never grew up. They also were very realistic and saw the ranch as a good economic opportunity. But they truly did want to keep the Wild West alive. They did it with the 101. It became a place, ultimately, where the West of myth and the West of reality collided.”

That passion wasn’t enough to keep the 101 intact, though. George Jr.’s death in 1929 marked the beginning of the end for the 101 Ranch. Of the original entrepreneurs and Wild West evangelists, only Zack remained; he was no businessman. For years the Miller brothers played fast and loose with the ranch’s proceeds. All of the brothers drew from the same bank account for their various investments, and nobody paid much attention to increasingly anemic profits. The 101 Wild West Show had been a huge drain on the ranch’s finances. It left behind a trail of lawsuits in the cities it visited. An overwhelmed Zack had no choice but to pay out.

The crash of 1929 and the Great Depression hit the 101 as hard as any corporate endeavor, and in 1937 Zack declared bankruptcy. The federal government seized the 101, divided it into parcels and it sold to individuals. It was an ignominious end to America’s largest ranch. But its legacy as an idea, a tribute to the Wild West lifestyle, lived on in popular culture, particularly in film and television.

In 2008, Tulsa’s Gilcrease Museum acquired the largest collection of 101 Ranch memorabilia in the nation from private collectors. The museum laid out $2 million for almost 4,000 pieces of 101 Ranch history. Among many other pieces, the collection includes many belonging to Lillian Smith. The collection was put on display in 2009, the first comprehensive exhibit of the ranch’s history.

The 101 became a National Historic Site in 1975, but all you’ll find there today are a small picnic area and the restored building that once held the ranch’s headquarters. The remainder of the ranch buildings were lost to dilapidation and fire. The grave of Bill Pickett and a monument to Chief White Eagle, a longtime friend to the Millers, sit on top of Cowboy Hill, recently acquired by the 101 Ranch Old Timers Association.

The ruins of the 101 have a quiet gravity. They mark not just the former site of the long-gone largest ranch in America; they serve as a reminder of the most important pulpit of Wild West mythology in America, a mythology that still runs deep and strong in America.