How Oklahoma cares for people with developmental disabilities has changed drastically in the last century. Institutionalization was the norm one hundred years ago, but ideas, beliefs and perceptions have evolved, leaving most of those institutions empty today.

The Beginnings:

From the impetus of statehood, the legislature realized that parents and families of people with disabilities needed help caring for their loved ones, but community-based supports and services did not exist. The idea at the time was that institutionalization was the best option.

“There was this idea that if [care] needed to be specialized, people might need to be with other people like themselves,” says Beth Scrutchins, division director of Developmental Disabilities Services, a division of the Oklahoma Department of Human Services. She mentions that due to misconceptions or ignorance, some feared that people with developmental disabilities could be dangerous, or that they needed extra protection themselves. “It was kind of all over the place,” she says.

Just after statehood, the first such institution was opened in Enid and named the Oklahoma Institution for the Feeble Minded. (Nomenclature referencing people with disabilities has undergone a lot of change through the years as well, resulting in frequent name changes.) Among other names, this home became the Enid State School, and much later, the Northern Oklahoma Resource Center.

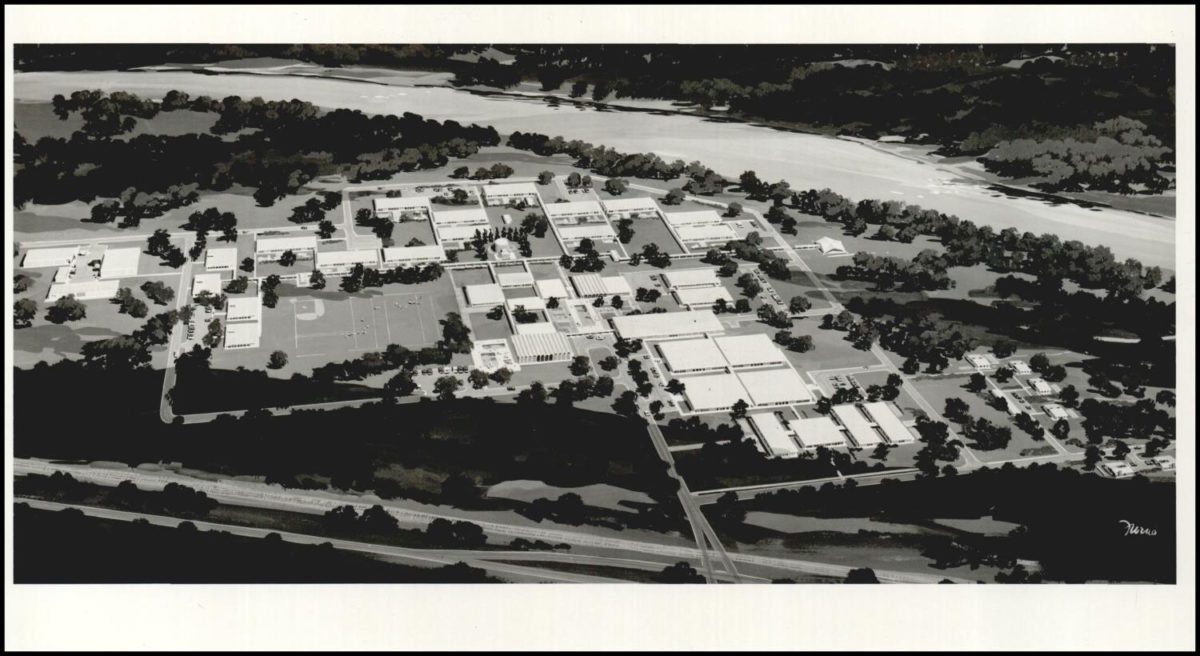

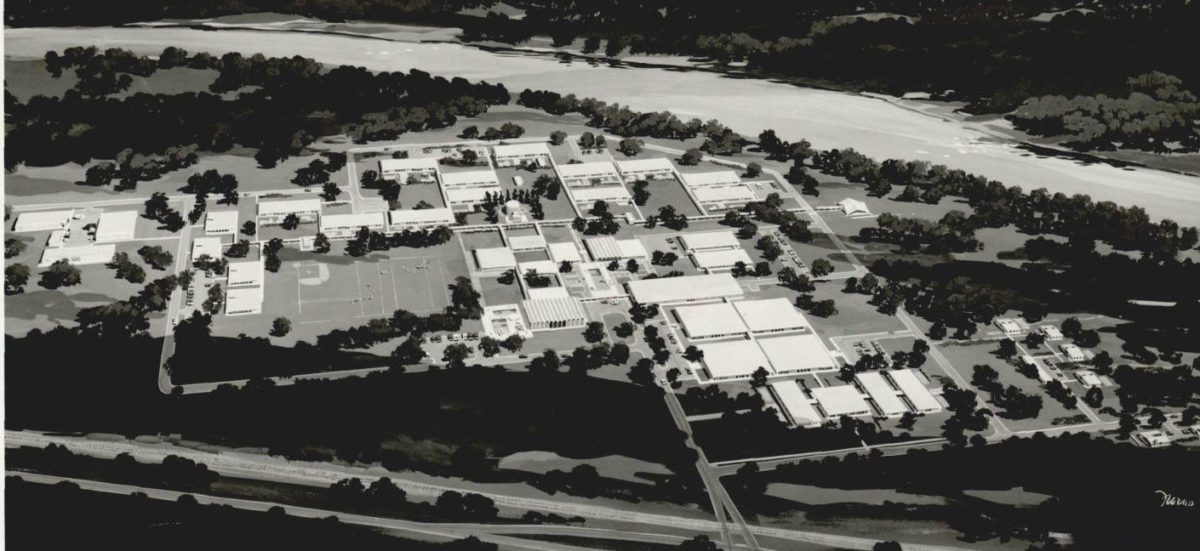

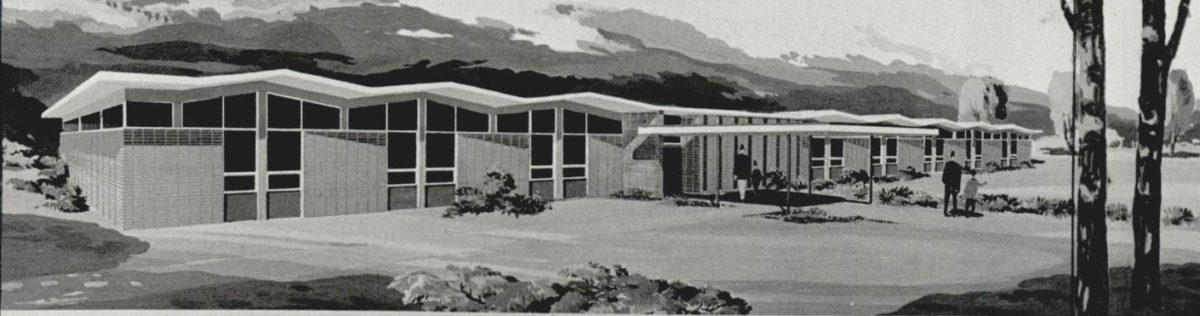

What would become the Southern Oklahoma Resource Center in Pauls Valley in 1992 started out as a training school for boys in 1907, later transforming into a center for people with intellectual disabilities in 1953, named the Pauls Valley State School.

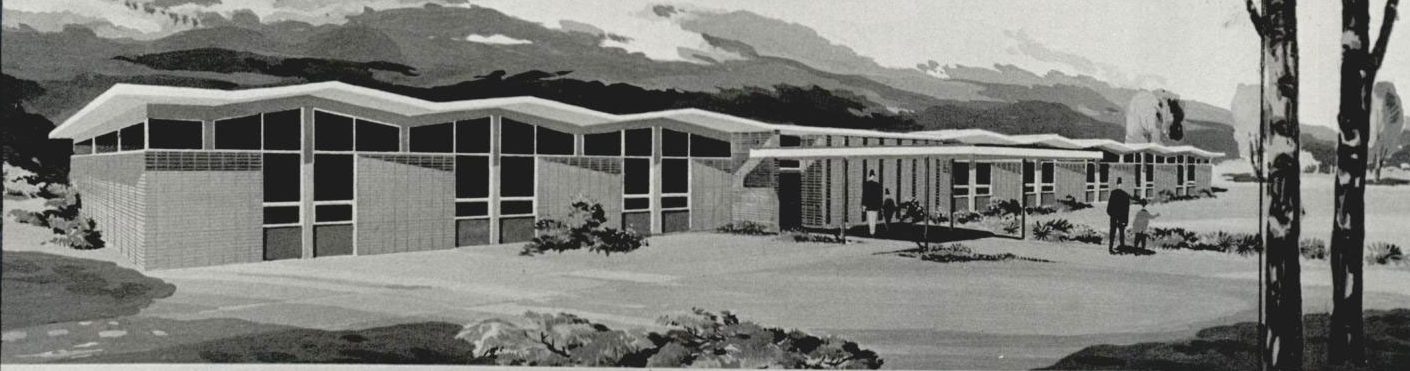

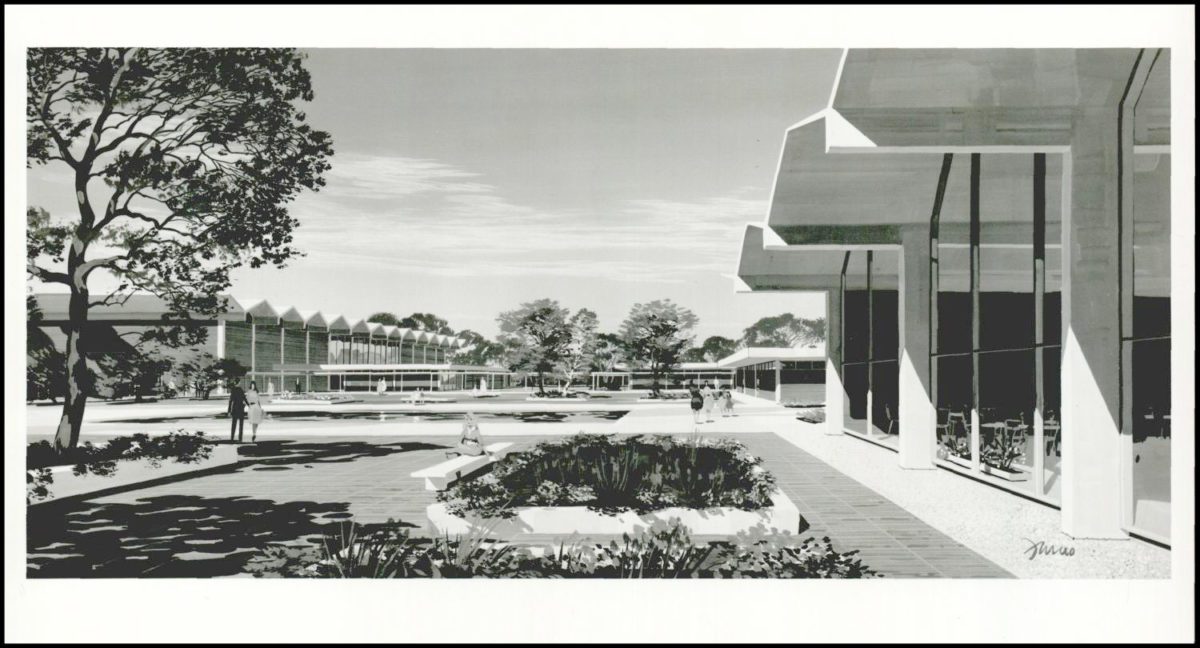

An additional institution, and one that would become infamous later – the Hissom Memorial Center in Sand Springs – opened in the 1960s to provide additional beds when the other two locations had become overcrowded. Hissom was considered to offer state-of-the-art service to this population at the time.

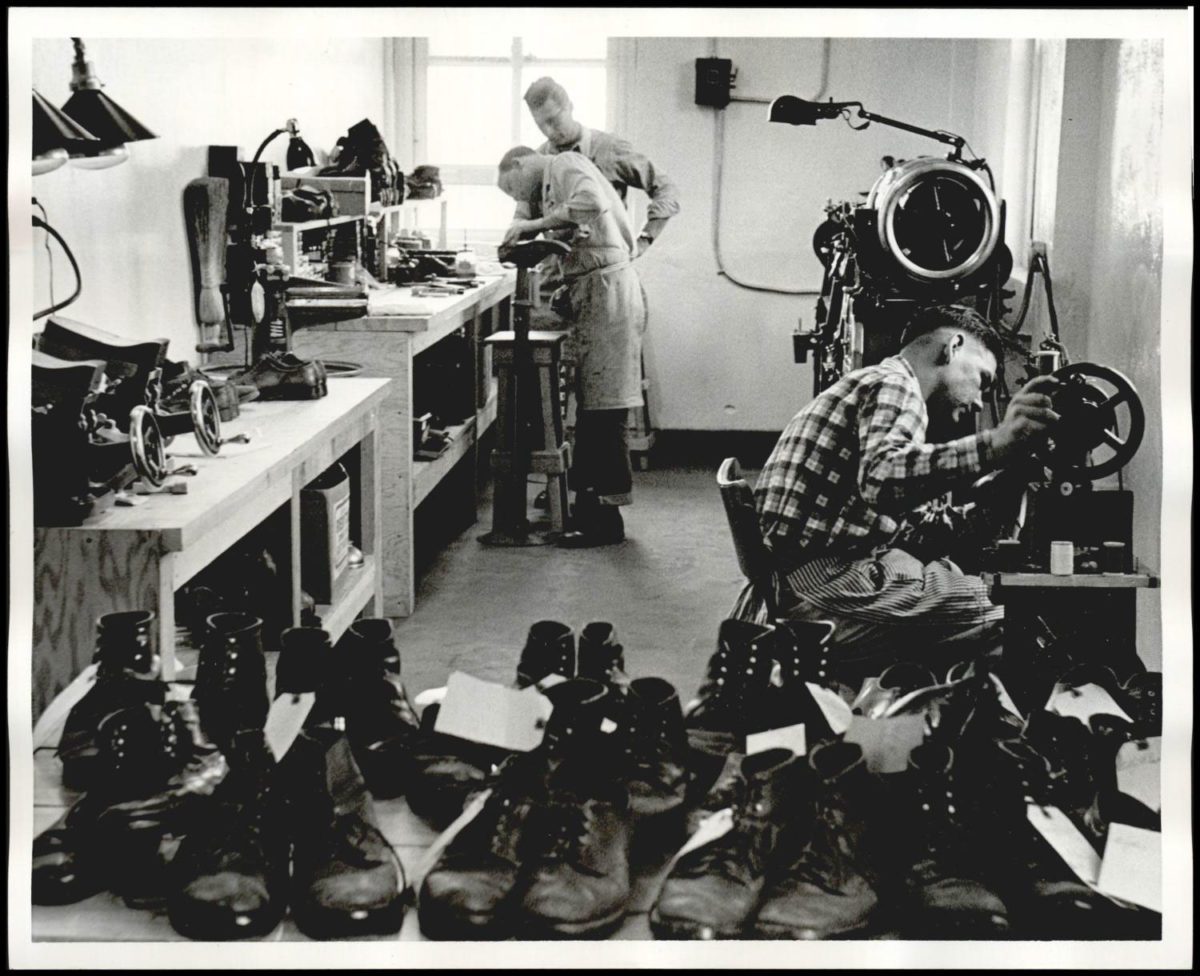

However, despite quality care, the focus of these institutions was centered solely around medical treatment, says Scrutchins. It was a campus-like atmosphere with everything provided within the facility.

“There were some people that we served in the community who moved there as toddlers, [and] who lived their entire lives there on the campuses,” says Scrutchins.

Pauls Valley State Hospital, photo by Richard Cobb

The Enid state school for ‘mentally defected,’ photo courtesy the Oklahoma Historical Society

Pauls Valley State Hospital, photo by Dick Peterson

Pauls Valley State school, photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

The Hissom Memorial Center in Sand Springs, photo by Ben Newby courtesy the Oklahoma Historical Society

The Hissom Memorial Center in Sand Springs was shut down in the 1980s after a lawsuit was filed by residents’ families. Photo by Ben Newby courtesy the Oklahoma Historical Society

The Hissom Memorial Center in Sand Springs, photo by Ben Newby courtesy the Oklahoma Historical Society

Major Changes:

Perceptions shifted. In 1985, two events took place that would drastically change the way services were provided to people with disabilities. First was the creation of a waiver program, which provided the option to receive services outside an institutional setting. The second occurred when families filed a lawsuit against the Hissom Memorial Center, which resulted in the court-ordered closing of that facility.

“When we closed the Hissom Memorial Center, we had to create a community program that we didn’t have. We were court-ordered to do that, and people saw that people [with developmental disabilities] could live in their communities, they could live in their family homes with support, or they could live in their own homes, supported, rather than having to be in that institutional, medical setting,” says Scrutchins.

Services are now provided based on each individual’s needs, rather than as a group in an institution. The Northern and Southern Oklahoma Resource Centers were closed in 2014 and 2015 respectively. People with disabilities now have access to a variety of services – everything from living together with a few individuals in a group home, to round-the-clock nursing care in their own family home, to a simple piece of technology that makes it possible for them to live alone, says Scrutchins.

“People are so much more capable of doing things, especially people with developmental disabilities, than people 50 years ago gave them credit for,” she says. “We know people in the community working full time jobs and living independently or with minimal supports. It is a huge paradigm shift.”