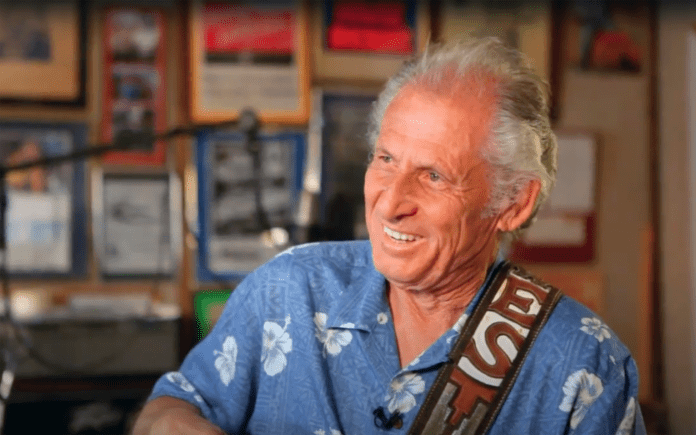

During a recording career that stretches back a remarkable 67 years, Tulsa’s Wes Reynolds has been inspired by a ton of different people, starting back in the late ’50s with classic rock ‘n’ rollers like Elvis, Chuck Berry and Little Richard. The inspiration for his newest disc, however, came from a much more personal and tragic place.

“This album came about because I wrote a song called ‘In the Afterglow,’” he explains. “It was a tribute to my oldest son, Corey, who died some years back. He had mental illness. He’d gone to Atlanta, Georgia. He was a journeyman electrician, and he started a business down there. He was pretty successful at it. Then things started going sideways. I did all that I could to try to help him, and finally I went down there, got him, moved him back here, and tried to get him some help.

“He just wouldn’t stay with that, you know? He’d disappear, and he’d be on the street, and I’d be out looking for him and not finding him. I worried a lot about him. Finally, I turned it all over to God, and when I did that, the next step was that he was gone. So I guess that’s what was supposed to happen.”

The song, which holds out hope for reuniting with loved ones in the next life, “just rolled out of me,” says Reynolds, as did another inspired by the loss of his son, “Life Without You.”

“I went through a lot just being a father that loved his son, and I know there are many people who have to experience mental illness with family and friends and so forth,” he adds. “I’d just like to maybe bring some awareness about that to people, to get people thinking about what they can do to help.”

While there are other deeply emotional numbers on the new disc, In the Afterglow is hardly a downbeat record. It opens with a classic Reynolds 12-bar blues, horn-accented, called “Bad Case of Love,” and ends with a reflective tune called “You Were Never Mine,” done in a 1950s ballad style that evokes the sense of loss that often accompanies nostalgic thoughts. Along the way, funky blues alternate with heartfelt ballads; there’s even a comedic tune (“To Far North”) bemoaning how hard okra, collard greens and hog jowls are to find once you leave our part of the country.

It’s Reynolds’ first record since 2009’s Burnin’ the Piano Down, and it marks his debut as a Muscle Shoals recording artist. Except for some vocals recut at Tulsa’s Church Studio, In the Afterglow was created entirely at Fame Recording Studios in Muscle Shoals, Ala., one of the longtime homes of the so-called Muscle Shoals Sound. That sound – R&B and funk elements like horns and Hammond organ combined with a kind of gritty country-influenced underpinning – echoes through Reynolds’ CD to great effect.

Why Muscle Shoals?

“I’d thought through the years that I’d like to go down there,” Reynolds says. “I had some other things I’d written, and I had the ways and means to record again. I did a song some time ago called ‘Doggone, My Doggone Dog’s Gone’ down in Nashville, with Elvis’s vocal group, the Jordanaires, behind me, so I was thinking about going back there. But then I thought, ‘Well, I’ll just go to Muscle Shoals and see what they’re all about.’”

He hired the band and called his own shots on the new disc. As you might imagine, that was a completely different experience than he’d had with his first record, “Trip to the Moon” – although that, too, was done at a place that would achieve an amount of fame.

In the 1950s, an Oklahoma City recording studio owned by Gene Sullivan, half of the country-music duo Wiley & Gene (“When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold Again”), became the destination for young Oklahomans experimenting with the new sounds of rock ‘n’ roll and rockabilly. Among their number was 15-year-old Wesley Reynolds of OKC, winner of a 1957 talent show sponsored by a Stillwater man named Bill Burden, owner of the small Rose Records label.

After he’d won the competition, Reynolds recalls, Burden “came to me and said, ‘We’re going to sign you to Rose Records and give you a two-record contract. And we’re gonna have a hit record. Now, I want you to go home and write a song called “Trip to the Moon.”’

“At that time, the headlines in the paper were all about how some day man was going to walk on the moon. So I go home and write – try to write – a thing called ‘Trip to the Moon.’ We went over to Gene Sullivan’s recording studio, and they had musicians from Al Good’s Orchestra to back me on this thing. I didn’t like that at all because I couldn’t get the sound I wanted, but I didn’t have anything to say about it.

“We recorded it, and they put it out on the Rose Records label. They took out a full-page ad in [the music-industry magazine] Cash Box, with my picture on it and the names of all the distributors and everything. They told me it cost $1,500. I quit school – my parents didn’t want me to, but they let me – and Rose Records put me on the road. We joined a tour with Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis and Ronnie Self, and we played the Cimarron Ballroom in Tulsa and went on to Joplin and Kansas City – about a two-week tour.”

Despite the promotion, “Trip to the Moon” didn’t make a significant impact on the national charts, and neither did his follow-up single, a rockabilly version of the Johnnie Lee Wills Western-swing hit “Rag Mop.” Reynolds recalls that he made no money on either one. (In fact, on the label for “Trip to the Moon,” Burden gets sole writing credit.) However, it was enough to launch Reynolds on a musical career that’s now lasted for well over six decades, re-igniting after he moved to southern California to live with his grandparents and go back to school, and continuing until 1970, when he quit the road and moved to Tulsa.

“I’d been playing the Vegas circuit for about five years at the time, all those towns in Nevada,” he remembers. “We were putting my son, Corey, in schools in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada. My mother and dad had moved to Tulsa, and my dad wanted me to move back and go into business with him, so I did.”

Reynolds continued, however, to play and record. He built a studio in his Tulsa home. And he found out that those teenage rockabilly records he’d cut in the distant past had made him something of a celebrity with hard-core fans of the genre.

“I went to Vegas last year and did the Viva Las Vegas rockabilly concert at the Orleans Hotel. It’s been going on for years. I did “Trip to the Moon” live there for the first time since I got off the road in ’58,” he notes with a chuckle. “A lot of people from Europe go to the thing; I get mail from Sweden, and Germany, and the UK, wanting autographed pictures. Evidently, I’ve stirred up a little commotion over there, and it’s all about that first record, and my next few records after that.”

At this writing, the Official Wes Reynolds Website was under construction. Featuring vintage posters and other career memorabilia along with Reynolds recordings, it was due to debut in August.

Reynolds’ 2023 performance of “Trip to the Moon,” in front of a packed house at the Viva Las Vegas event, has been preserved on YouTube.