[dropcap]For[/dropcap] many years now, whenever I’ve gotten the itch to add to my collection of autographed baseball and football cards, I’ve usually wound up at S&S Sports Cards in Broken Arrow, where the exceptionally knowledgeable young man known by patrons as Tattoo has been an affable source of guidance.

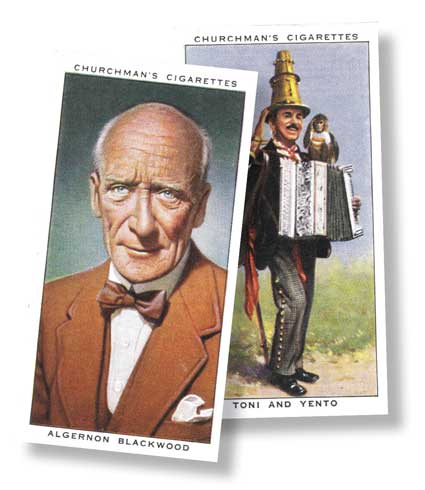

A while ago, however, while I was nosing around there, something caught my eye that had to do with neither baseball nor football nor autographs. Back on one of the store’s tables, encased in plastic sleeves, was a set of color cards called collectively In Town To-Night, with each card measuring roughly 2 ¾ inches by 1 ½ inches and depicting one of a variety of Britishers from a bygone era. Recognizing a couple of the folks depicted, like famed ghost-story writer Algernon Blackwood and Dante the Magician, who’d co-starred with Laurel and Hardy in the 1942 feature A-Haunting We Will Go, I gave the 50-card collection a closer look, saw that the price was right and took it home for further study.

I knew a little about cigarette cards; most baseball-memorabilia collectors do, thanks in part to the hoopla surrounding American Tobacco Company’s Honus Wagner card from the early 20th century. Part of a set of major-leaguers, the card was withdrawn after Wagner, star shortstop of the Pittsburgh Pirates, objected because he didn’t want kids buying cigarettes in order to get it.

By the time the Wagner card first came out in 1909, tobacco companies had been inserting these little tchotchkes in their cigarette packages for a couple of decades, not only to provide extra impetus for purchasing a particular brand, but also to stiffen the packaging. In addition to baseball players, subjects included movie stars, plants and animals, military heroes, and American Indian chiefs, among many others.

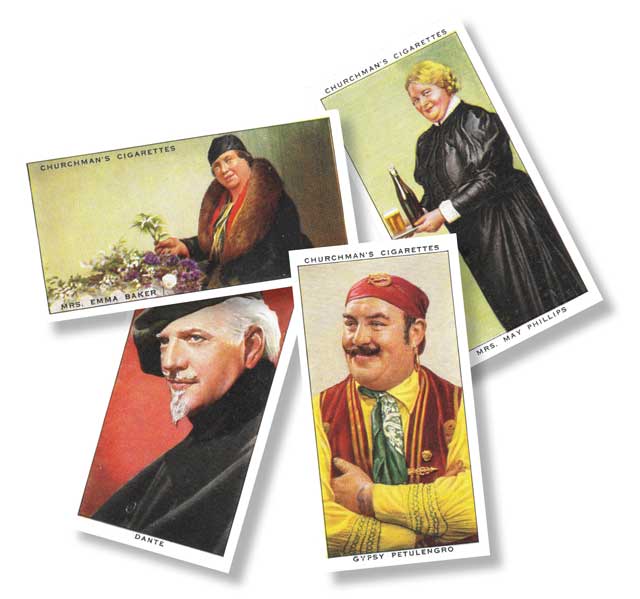

And then there was the collection of souls from In Town To-Night. In addition to Blackwood and Dante, both pretty famous guys in their time, those immortalized on cardboard by Britain’s Churchman’s Cigarettes included Mrs. May Phillips, “The Perfect Barmaid” (“Having been a barmaid in various parts of London for over thirty-five years, her tales of days gone by, when barmaids had to endure long and trying hours and were treated little better than dirt, contrast vividly with present-day conditions”); Gypsy Petulengro, “Astrologer and Palmist,” a man who “has read the hands of most of the European monarchy”; Miss May Storey, “Woman Detective” (“[N]ot only is she engaged in detecting shoplifters, but has to shadow people of every type, from dope pedlers to confidence tricksters, and from blackmailers to missing heirs.”); and Toni and Yento, “One-Man Band,” a musician and his monkey “well known in London, at the seaside, and on racecourses.” There’s even one of Mrs. Emma Baker, a woman who’d been selling flowers at Piccadilly Circus for the preceding 28 years.

[pullquote]I’m afraid, as a society, we just don’t find any regular folks very “interesting” any more.[/pullquote]These and the others depicted on this 1938 tobacco-card set all had one thing in common: They’d appeared on the BBC’s Saturday night radio program In Town To-Night, a talk show that had begun in 1933 and would continue until 1960, always introduced by an announcer saying, “Once more we stop the mighty roar of London’s traffic and, from the great crowds, we bring you some of the interesting people who have come by land, sea and air to be In Town To-Night!” Judging from the set, these “interesting people” included, but were not limited to, street entertainers, fruitiers, pilots, synagogue readers, butlers, photographers, explorers, booksellers, artists and plumbers – with those profiled earlier, an egalitarian assemblage if there ever was one.

As I spent some time with photos and profiles of these long-deceased people who did a radio show in London back before most of us were born, I found myself thinking not so much about how remarkable it was that this set of cards printed nearly 80 years ago made it across the Atlantic to land in a ballcard shop in Oklahoma, but how exactly our popular culture got from a talk show featuring “interesting people” from everyday life to the Kardashians and Naked and Afraid.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m no dewy-eyed nostalgiac, pining for a time when things were simpler and easier and lovelier. When those cards came out, the unspeakable horrors of World War II were on the horizon; social, racial and sexual inequality ran rampant; and people were dying en masse of diseases that are now either eradicated or treatable. Even the substance that brought the cards into existence, tobacco, has now been seen for the health menace it represents.

But there’s something here that goes deeper, right to our collective soul. I’m afraid, as a society, we just don’t find any regular folks very “interesting” any more. As is the case with many of us old poops who didn’t grow up with the internet, I have a tendency to lay part of it off on electronic media. Because I came of age in the ‘60s, I also have a tendency to blame disco. Seriously.

In the mid-’70s, when the discotheque culture started creeping into Oklahoma, many of my live-music-loving friends and I saw it as a menace, since to a great extent the discos replaced onstage bands with recorded music. I didn’t fully realize why I was anti-disco until many years later, when I taught a college class on the history of rock ‘n’ roll. In our textbook, Rockin’ in Time, Casablanca Records president Neil Bogart characterized disco patrons as people “tired of guitarists playing to their amplifiers. They wanted to be the stars.”

Added author David Z. Szatmary, “Disco, unlike most rock-and-roll, allowed the participants to assume primary importance. Not involving musicians standing on the stage, it centered on the audience.”

In other words, the musicians simply weren’t as “interesting” to those who came to the club as they themselves were.

Disco became the perfect soundtrack for the Me Decade, as the 1970s have often been dubbed, and it marked the beginning of a cultural shift in our entertainment and in our lives. Flash-forward to now, when the noise of democracy has become, too often, the sinister silence of a “send” button, electronically whisking anything we want to say to an uncountable audience. Too often others, especially those with whom we disagree, are seen only as ciphers, not as human beings, never mind “interesting” ones. Of course, the fact that so many online comments are made under pseudonyms doesn’t help put a face on anybody.

At the same time, what entertains us when we’re not aggrandizing ourselves must become baser and more exploitative, if only to drag our rapt attention away from ourselves. Don’t get me wrong: I’ve long loved alternative culture. But it’s only “alternative” when there’s a mainstream culture to play against it. Look around and see what’s become “mainstream,’’ in our entertainment and in our politics. How long do you suppose one of the people depicted on the In Town To-Night set would last in 2016 America before his or her head exploded?

Although he’s not well-known today, the pianist and wit Oscar Levant had a long run as an American entertainer. In his introduction to Levant’s 1940 book A Smattering of Ignorance, playwright S.N. Behrman recalls his astonishment when Levant met up with a longtime enemy and the two were nothing but cordial. When Behrman asked him about it, Levant said, “Well, you know I hate ‘em until they say hello to me.”

Nothing beats face-to-face kindness and human interaction. And sometimes, nothing’s kinder and more interactive than interest in another person’s story. That’s one thing that hasn’t changed since In Town To-Night had its nice long run, simply by putting “interesting” people on the air.