For Halloween this year, how about the story of a native Oklahoman who went on to become the only actor ever to play all four of the famed Universal Pictures horror characters of the 1930s and ’40s: the Wolf Man, the Mummy, Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster?

That’s a remarkable, one-of-a-kind achievement. But what may be even more remarkable about Lon Chaney Jr. is that he survived at all.

In a July 28, 1940 piece for the Sunday supplement magazine This Week, writer Frederick James Smith began his profile of Chaney with these words: “On a bleak, cold February day just thirty-four years ago a pioneer doctor took a tiny, premature two-and-a-quarter-pound baby and, smashing the ice of a small lake outside Oklahoma City, dashed the infant in and out of the freezing waters. It was his desperate way of shocking life into the sluggish child who balked at existence.”

The child, dubbed Creighton (his mother’s maiden name) Tull Chaney, had been born to a couple of small-time vaudeville performers, on tour at the time. According to Smith, after Creighton’s birth, his father, Lon, left showbiz for a while, taking a job as a carpet layer with an Oklahoma City furniture store in order to provide for his son. That lasted until the senior Chaney and his wife got another offer with a touring show. Then, they were off again, with the infant Creighton spending a significant amount of time “backstage in a cotton-lined shoe box with holes punched in the lid – when he wasn’t sleeping in a small hammock woven by his dad and hung over his dressing table.”

By 1914, the marriage had dissolved, with Lon Chaney gaining custody of eight-year-old Creighton. The elder Chaney had begun working for Universal Pictures, and by the late 1920s, he had worked his way up to being the movies’ top portrayer of weird and unusual characters.

Although he was a famous star, Lon Chaney did what he could to dissuade his son from following the same path. In fact, This Week’s Smith wrote that keeping his boy out of show business was an “obsession” with Chaney. So, from a very young age, Creighton explored other avenues of employment.

“Regular schooling wasn’t for me,” he told This Week. “I liked getting around. At twelve I was a migratory fruit picker like those John Steinbeck writes about. I couldn’t stay put. I worked as a boilermaker, a butcher boy, a slaughterer, a plumber. Acting never dawned on me.”

After his dad’s 1930 passing, however, Creighton began thinking more about the profession that had made his surname famous. Finally, he left his job as a secretary at a water heater company and struck out for pictures; by 1932, he was doing stunt work and appearing in small parts, which led to bigger roles and, in 1935, a name change to Lon Chaney Jr. This came about, it seems, because of studio insistence, as a quote, attributed to him in the 1991 book Horror Film Stars by Michael R. Pitts, makes clear: “I am most proud of the name Lon Chaney because it was my father’s and he was something to be proud of. I am not proud of Lon Chaney, Jr., because they had to starve me to make me take this name.”

Perhaps he learned to be proud of it, since his career began to ascend after he traded “Creighton” for “Lon Jr.” In 1939, he hit the next level, with his breakthrough performance as the slow-witted and ultimately tragic farmhand Lennie in the movie version of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. It was nominated for several Academy Awards, including Best Picture (losing to Gone with the Wind).

Unlike his namesake dad, he had not been playing horror roles. In fact, at the time Of Mice and Men came along, he seemed to be forging a name in westerns and serials. According to an interview with Barrett C. Kiesling in the Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch on May 25, 1941, that was intentional.

“ … I decided that to establish Lon Chaney Jr. as quite a separate character from his father,” Chaney told Kiesling, “I would practice particularly hard on a line for which he was not fitted … vigorous action Westerns.”

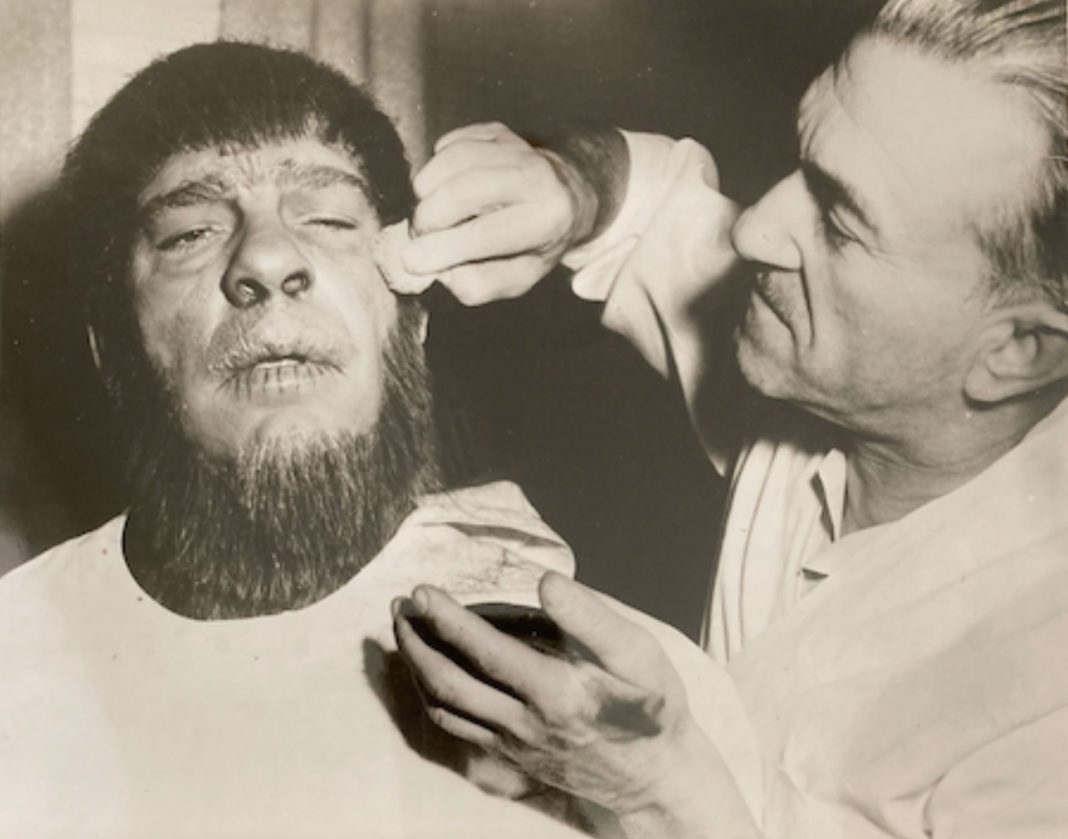

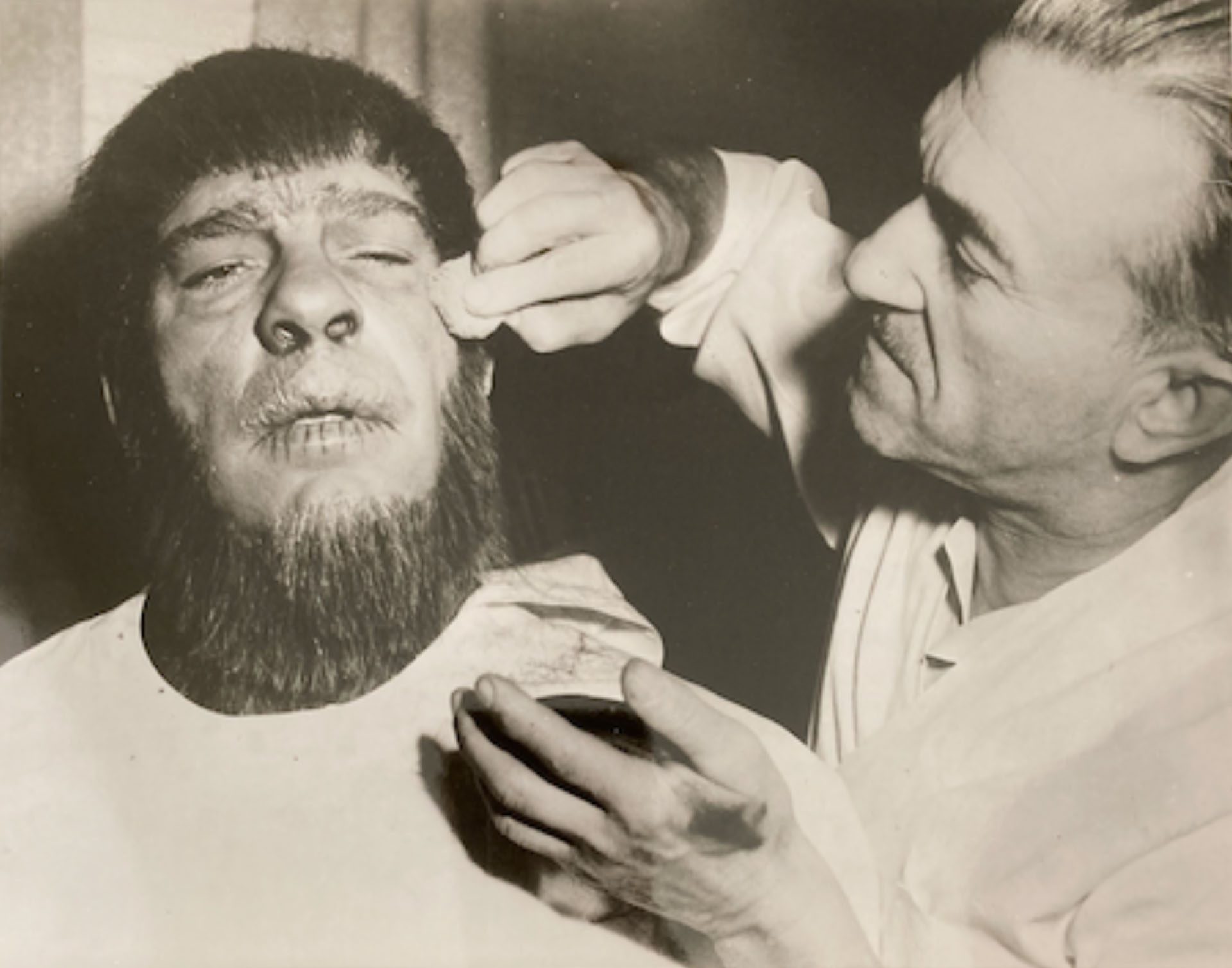

His filmography shows that tack worked – for a while. However, the same year he gave Kiesling the interview, Universal released The Wolf Man, with Chaney in the title role. And for the rest of his life, he – like his dad – would be known as a horror star. During his prime decade of the ’40s, he would play the lycanthropic Lawrence Talbot four more times, in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945 – in which Talbot is temporarily cured of his werewolfism) and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). Of the four major Universal monsters he portrayed, the wolf man was the only one he originated, so it’s understandable that he did more features as this character than he did as any other.

Still, he racked up plenty of other monster portrayals. He was the undead Egyptian Kharis in The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), The Mummy’s Ghost (1944) and The Mummy’s Curse (1945); Dr. Frankenstein’s monster in Ghost of Frankenstein (1942); and Count Dracula in Son of Dracula (1943), which co-starred another Oklahoma City native, Louise Allbritton. To give an idea how ubiquitous he was in Universal Pictures’ horror shows, in one year – 1948 – a moviegoer could have seen him onscreen as the wolf man (in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein) as well as Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster, respectively, in a reissue double-feature of Son of Dracula and Ghost of Frankenstein.

By the time The Mummy’s Tomb came around, Universal had dropped the “Jr.” from Chaney’s name. As Lon Chaney, he would continue making movies for nearly three more decades, and while several of them were outside the horror genre – including such notable entries as 1952’s High Noon and 1958’s The Defiant Ones – Chaney’s name would continue to be synonymous with horror pictures, just as his dad’s had been a generation earlier. It may not have been exactly what the former Creighton Chaney wanted, but that’s what happened. In fact, one of the very last films he did was Dracula vs. Frankenstein, directed by Al Adamson, a cult figure known for his outrageous low-budget pictures. In Dracula vs. Frankenstein, Chaney didn’t play either monster; instead, he was a Lennie-like figure called “Groton.” Two years after the picture’s initial release, Chaney was dead from throat cancer – the same disease that had taken his father’s life 43 years earlier.

Of course, all of that was still ahead of him in 1941, when his This Week interview with Frederick James Smith came out in Sunday newspapers all across America. It closed with this reflection from the then up-and-coming actor:

“When I flew East the other day I looked down and saw Oklahoma City for the first time since that dousing I got the day I was born. I thought of all these things that had happened since. Sure, I crossed up my dad’s wishes. But somehow I think he’d be happy now. Maybe I can get that name of Lon Chaney back up in the theater lights across America again.”