Arnell Dean made his career choice as a teenager, thanks to Emergency, which ran on NBC for six seasons in the 1970s. The show’s paramedics, Roy DeSoto and Johnny Gage with Los Angeles County’s fictonalized Squad 51, were Dean’s heroes.

“I watched it religiously,” says Dean, a 40-year emergency medical technician with EMSA in Oklahoma City. “Every episode, they saved somebody’s life.”

Robert Painter, program director for Tulsa Community College’s emergency medical services and paramedic program, also got hooked when he was young. At 18, he was already teaching CPR classes for the American Red Cross.

The Tulsa native attended the University of Oklahoma his freshman year and drove home from Norman about once a month.

“I would come across a wreck and wish I could offer more help,” says Painter, who became an EMT in 1978.

First responders are “just a breed above,” says Jim Winham, president and chief executive officer of EMSA (Emergency Medical Services Authority), which provides pre-hospital emergency care in central and northeastern Oklahoma. “They are selfless people who really have a calling to try to take care of other people and make a difference.”

TCC trains emergency medical responders, EMTs and paramedics with certificate and degree programs, Painter says, and all instructors are working paramedics. Students complete the paramedic program in three semesters.

“Some of our students already are employed by an ambulance service or fire department and are sponsored to take the course,” Painter says. “There’s a pretty good demand nationwide for nationally registered paramedics.”

Edward McConville, one of Painter’s adjunct instructors and a paramedic on a medical helicopter, says out of high school he “went into the Army National Guard and that kind of set the tone. My job in the reserves was field medic. I really enjoyed that part of it. When I went back to school, I got my EMT.”

McConville says he took to the air about nine years ago. Helicopter flights allow rapid transport to specialized facilities, such as trauma centers and heart hospitals.

Tulsa Life Flight takes paramedics training to new heights.

EMSA training in OKC involves a variety of exercises, including CPR.

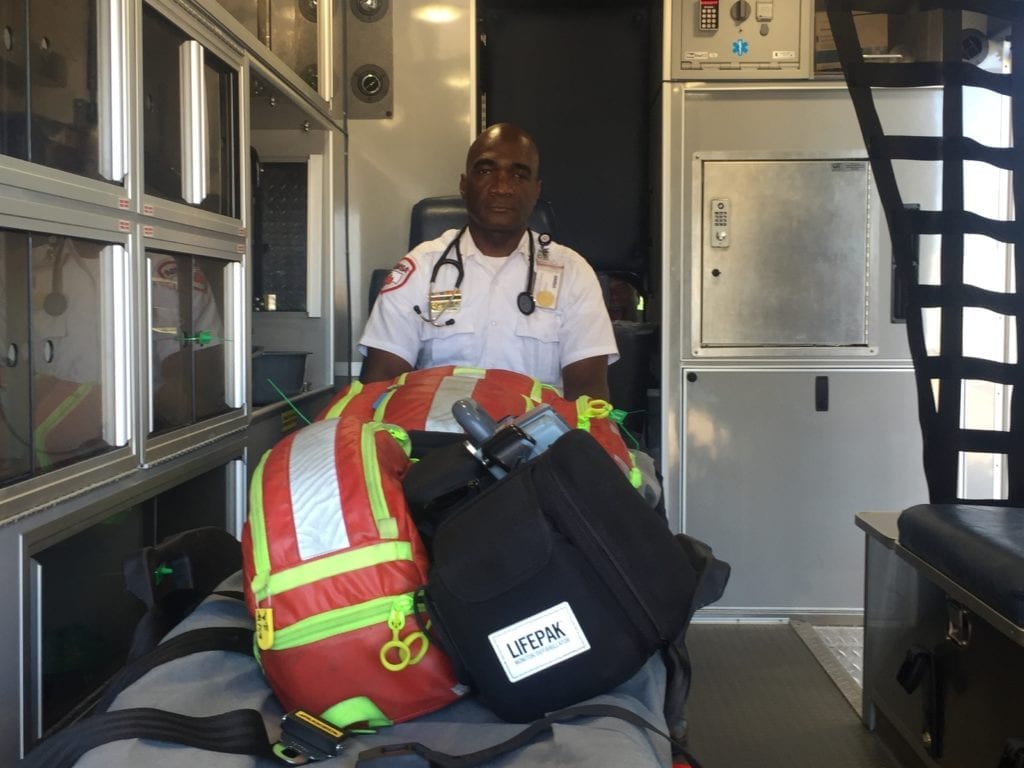

Arnell Dean, 40, was the first African-American EMT in the back of an ambulance in OKC.

Edward McConville works on a medical helicopter and teaches EMT certification at Tulsa Community College.

Arnell Dean, 40, was the first African-American EMT in the back of an ambulance in OKC.

Tulsa Community College offers training and certifications for emergency medical responders, EMTs and paramedics.

Some paramedics are trained to work on life flight helicopters.

“They are really beneficial in the rural parts of any state,” he says.

McConville says today’s paramedic students are better prepared than he was.

“A lot of that has to do with the equipment and the technology available today,” he says. “We have gone from doing things just because we’ve done them that way to doing a protocol that is evidence-based, so there is some science behind what we are doing.”

Hope Lowry, a TCC paramedic student scheduled to graduate in July, reflects Winham’s observations about selflessness.

“I’ve always loved helping people,” Lowry says. “I originally wanted to be a pediatrician.”

Lowry says she got sidetracked and studied business, but life experiences brought her back to health care. Her sister died a few years ago in a traffic accident, and her youngest daughter nearly died four years ago from a medical condition.

“I found myself thrust back into the medical field wanting to play a bigger role in my daughter’s health care,” she says.

Lowry, already an EMT and a hospice caregiver, says she wants to work in a hospital surgical department as a paramedic and continue on to nursing school next year.

“The pre-hospital setting is vastly different from the hospital setting,” Lowry says of emergency-care training. “It’s going to help me be a better nurse. If I can stick an IV in somebody while we are rolling down the road, I certainly can do it while we are sitting still.”

Painter says it’s not unusual for EMTs and paramedics to continue their educations. He earned a business administration degree and spent 26 years in Alaska, the last 18 as a fire chief and director of emergency services.

Emergency responders invariably say they love what they do, but Winham warns that stressors can take a toll.

“They have traffic to deal with and crowds at emergency scenes,” he says. “It’s a daily grind on them. You want to make a difference, but sometimes you can’t. People are going to die on you.”

Winham says EMSA has chaplains, peer support groups and a contracted mental-health provider to support workers.

“Sometimes it’s just difficult to go on,” Winham says. “It’s important to be able to release your feelings.”

Dean says pediatric cases can break his heart.

“To see little kids traumatized in a car accident, that’s stressful,” he says.

Dean, an EMSA chaplain, was on duty the day of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. For weeks after, he awoke in the middle of the night remembering what he had seen. Several of his co-workers changed careers afterward.

“The bombing catapulted me into really doing the job of critical stress management for the other employees,” Dean says.

When he retires, Dean says he would like to travel the country and speak to students about how he became the first African-American EMT in the back of an ambulance in Oklahoma City. EMSA hired him when he was 18 to do non-emergency runs while he attended school at night.

His parents and grandparents were worried he might face hiring discrimination, Dean says, and tried to prepare him for disappointment.

“But I aced the interview,” he says. “They wanted me on the job. They did everything in their power to make sure I got hired.”