“OKLAHOMA, where the wind comes sweepin’ down the plain / And the wavin’ wheat can sure smell sweet / When the wind comes right behind the rain!”

Yes, yes – we’re sure you’ve heard our state’s iconic song, but do you know when and how Oklahoma was founded? How about some of the state’s most influential figures and key historical moments? Just how important Native Americans are to the fabric of our state’s success? Well, if not, you’re in luck – we outline all that and more in the following pages to remind you that the land we belong to is, indeed, quite grand.

Oklahoma’s Beginnings

It’s likely that no state has a more complicated and distinct origin than Oklahoma.

The area east of the Panhandle was acquired in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, and soon became part of the schemes of Thomas Jefferson and succeeding presidents to force all Indian tribes west of the Mississippi River.

“Jefferson was convinced it would take many generations for white settlers to occupy all the Louisiana Purchase, and it took three,” says Oklahoma State Historian Matthew Pearce.

The first region to be known as Indian Territory would encompass the present states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and part of Iowa. Relocation by treaty began soon after 1800, and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 forced large numbers to present-day Oklahoma on what became known as the Trail of Tears.

After Kansas and Nebraska entered the union, more Indians were moved further south to present-day Oklahoma. Plains tribes were placed on reservations in the western half of the territory.

The Dawes Severalty Act gave the government the power to break up communally held tribal land and allocate it to individuals. The Unassigned Lands in Oklahoma were then opened for non-Indian settlement through land runs, a lottery and an auction.

The greatest impetus for statehood began after the Land Run of 1889. About 50,000 settlers began to clamor for statehood so as to gain representation in Congress, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Leaders in Indian Territory favored double statehood. When it became apparent that would not happen, white settlers lobbied to join the two territories. Oklahoma was admitted to the union on Nov. 16, 1907, as the 46th state.

Oklahoma after the land runs looked differently than people might imagine, Pearce says.

“We think of a homesteading family in the middle of the prairie with a dugout,” he says. “But most people moved to a town or city. The railroads were in the area, and had been involved in platting town-sites. Settlers started purchasing town lots to establish businesses.”

Though Oklahoma would come to prosper as an agricultural state, “it was tough to farm, especially the first year. But people were drawn to the opportunity of a chance to own land. The United States was rapidly industrializing, but still there was the perception that the way you can make yourself is through farming.”

Major Moments in Okie History

Our Founding

After residents of the Twin Territories voted for statehood in 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt admitted Oklahoma as the 46th state on Nov. 16, 1907.

On Dec. 3, Roosevelt announced to Congress: “Oklahoma has become a state, standing on full equity with her elder sisters, and her future is assured by her great natural resources.”

Pearce says he finds Oklahoma history interesting “because it serves as a microcosm of so many regional, national and trans-national stories. We are a very diverse and multicultural state. That ties into our history stretching back to the forced expulsion of Native and enslaved people here, to more recent stories of people finding a home here, such as refugees from the fall of South Vietnam.”

The Tulsa Race Massacre

Oklahoma’s major historical moments rarely happened in a vacuum. The Tulsa Race Massacre on May 31, 1921, took place shortly after the end of World War I, Pearce noted.

“Many African-Americans had served in World War I, had been to France to experience a society absent of Jim Crow segregation. They came home and were expected to again become subservient. They started advocating openly for civil rights.”

But many white Americans were out to strengthen segregation, Pearce says, with similar incidents of racial violence breaking out in Chicago, St. Louis and other cities.

Route 66

Next year, Oklahomans will celebrate the 100th anniversary of Route 66. It’s a highway that remains significant today.

“By the 1940s and 1950s, highway travel is starting to replace railroads for goods and for leisure travel,” Pearce says. “We see the proliferation of car culture. Businesses were developed to cater to travelers’ needs.”

Today, tourism is one of the largest industries in Oklahoma, Pearce says. Motorists who make the Route 66 journey from Chicago to Santa Monica, Calif., are vital to the industry.

Route 66 became a primary route for migrants to California, especially during the Dust Bowl.

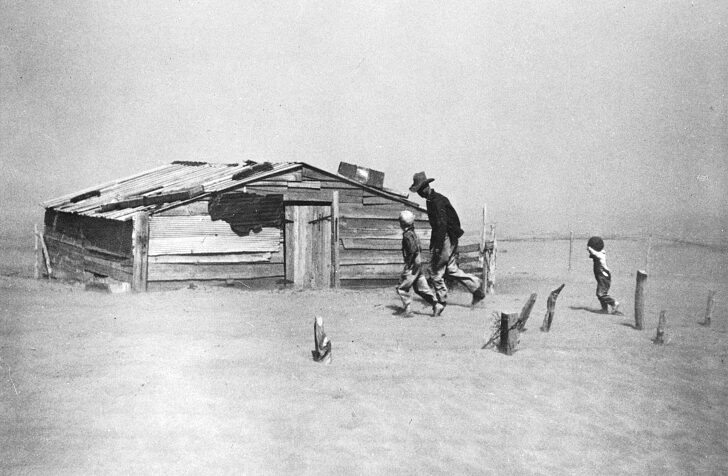

The Dust Bowl

“One of the most-requested topics for me to talk about is the Dust Bowl,” says Pearce, who works for the Oklahoma Historical Society. “There is no denying the absolute scale and severity of the Dust Bowl.”

The drought was worse in western Oklahoma and the Panhandle, but the exodus was greater elsewhere in the state, Pearce says.

In wheat country in western Oklahoman, “many farmers owned their land. The likelihood of them leaving their land was much less. But the migrant and tenant farmers in southern and eastern Oklahoma were forced out by landlords. They comprised what we think of as ‘Okies.’ Prices fell, and they stopped growing cotton.”

The Dust Bowl and Great Depression of the 1930s were followed by World War II, which brought a greater military presence to the state in the form of Tinker Air Force Base and other installations.

The Fight for Civil Rights

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a case brought by Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher that the state must provide instruction for Black students equal to that of whites. Fisher became the first African-American admitted to the University of Oklahoma law school.

Ten years later, schoolteacher Clara Luper and her students pioneered Oklahoma City’s sit-in movement at downtown lunch counters.

Many civil rights activists trace their roots to the All-Black Towns, Pearce says, which were founded by formerly enslaved people who had come with Indian tribes or migrated to the territory after the Civil War.

Shirley Nero, a retired educator who grew up in the historically Black town of Clearview, was among Black students who worked to better their opportunities after enrolling at East Central University in the late 1960s.

“We were going to break the barrier,” Nero says. “The white kids weren’t mean or hateful, it was just the way they prevented you from doing things.”

A Black student group was formed.

“We had dances. We created and performed plays. We had floats in the parades,” says Nero. “We had queen candidates. We had study groups in the library. We made friends with the president of the college and met with him every other week.”

By the time she graduated, Nero says, “it had made a huge difference. They came to respect our group. We advocated for our own rights, for the right to have a part in the student government.”

Sooner State Icons

Will Rogers was, in his day, the No. 1 radio personality, No. 1 at the movie box office, the nation’s most-sought-after public speaker and the most-read newspaper columnist, according to the curators at the Will Rogers Memorial Museum in Claremore.

Oklahoma has produced a giant share of luminaries, but for worldwide notoriety, it’s hard to beat William Penn Adair Rogers, born on Nov. 4, 1879, in Indian Territory near what would later become Oologah.

“Will Rogers’ human nature, wisdom and humor were nurtured on the sprawling frontier governed by Cherokee Indians,” according to his biography on the museum’s website. Rogers often expressed pride in his Native ancestry. He died in 1935 when a plane piloted by the famed Wiley Post crashed in Alaska.

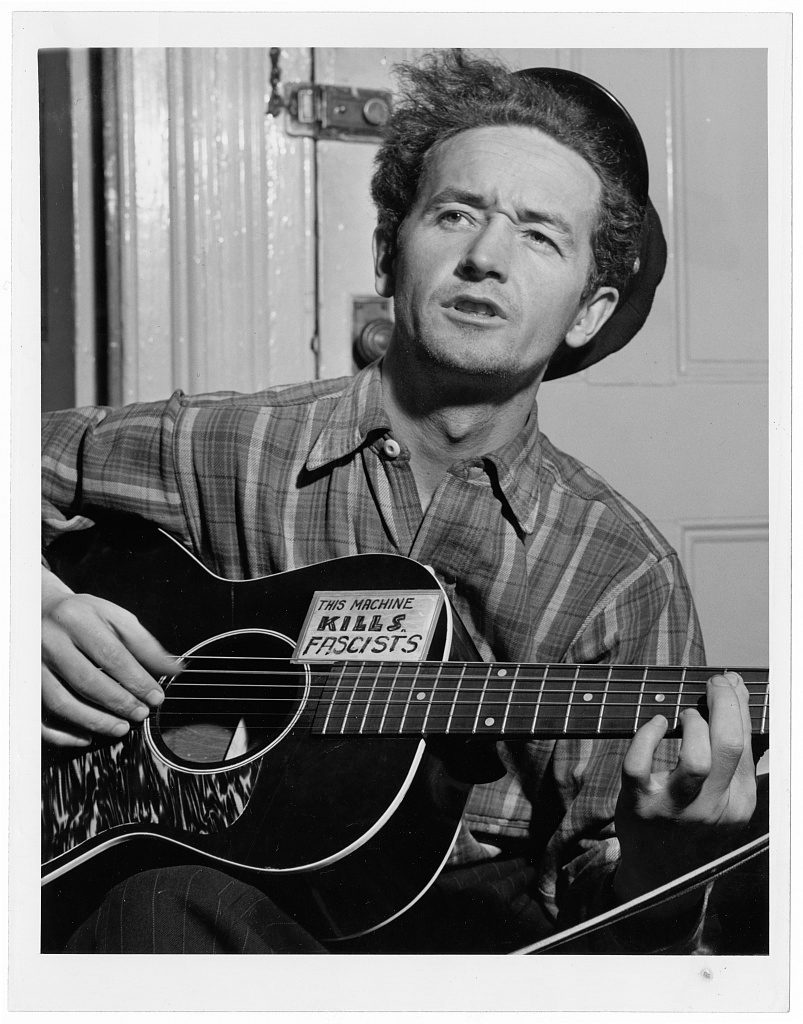

Woodrow “Woody” Guthrie, one of Oklahoma’s most creative native sons, wrote two autobiographical novels, numerous essays and articles, more than 1,000 songs and poems and hundreds of letters, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. He was a major influence in the urban folk revival and social protest songwriting. Born on July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Guthrie moved to Pampa, Texas, in 1929, where he experienced the Dust Bowl years. He learned to play guitar, fiddle, banjo and mandolin. When he made money from playing at dances, he often gave it to someone he thought needed it more, according to the OHS.

In the early 1940s, he wrote some of his best-known songs including “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know You,” “This Land Is Your Land,” and “Bound for Glory.”

By 1950, Guthrie was showing symptoms of Huntington’s disease. He died on Oct. 3, 1967. His descendants, including son Arlo, have carried on his tradition of musical performance and social activism. A music festival is held in his honor every July in Okemah.

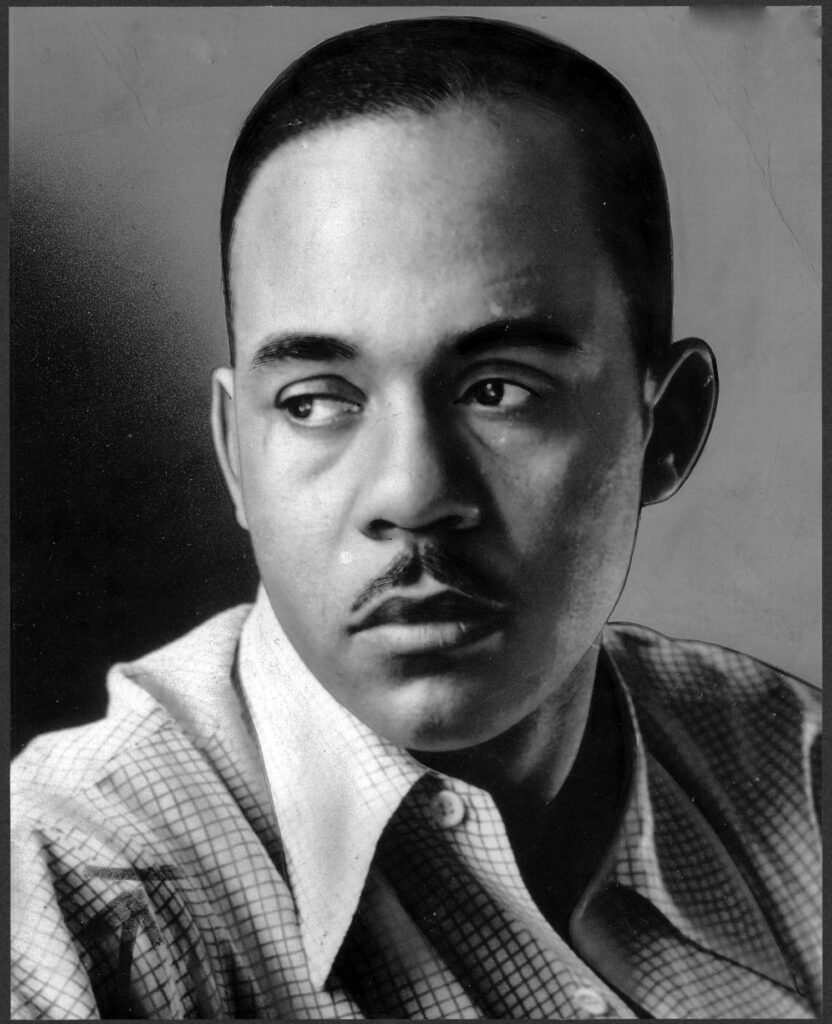

Ralph Waldo Ellison, born in OKC in 1914, was the grandson of slaves and is best known as the author of Invisible Man, the 1952 novel that addressed many of the social issues faced by African-Americans in the early 20th century. More than 40 years later, Nobel Prize winner Saul Bellow declared: “This book holds its own among the best novels of the century.”

Ellison spent the two years in Rome as a Fellow of the American Academy and taught at Bard College, the University of Chicago, Rutgers, Yale and New York University, according to the OHS. He died in 1994.

Actor, director and producer Ron Howard was born in Duncan in 1954. His father, Rance, majored in drama at the University of Oklahoma. Ron made his film debut at the age of 18 months. In 1960 was cast as Opie on The Andy Griffith Show. In the mid-1970s he became America’s favorite teenager in Happy Days.

Howard’s directorial debut came in 1977 with Grand Theft Auto, in which he also served as screenwriter and star. His smash hits include Splash, Night Shift, Cocoon, Parenthood, Apollo 13 and The Grinch. A 1992 film, Far and Away, told the story of an Irish couple who come to Oklahoma Territory to take part in the Cherokee Outlet Land Run, according to the OHS.

Jim Thorpe, born in 1888 on the Sac and Fox Reservation, is remembered as one of the greatest sportsmen of the 20th century, winning two Olympic track and field golds and playing baseball, football and basketball at the highest level, according to Olympics.com.

In presenting Thorpe with two gold medals in Stockholm in July 1912, King Gustav V of Sweden said to him: “You sir, are the greatest athlete in the world.”

Thorpe played baseball for the Rocky Mount club in North Carolina in 1909 and 1910, receiving small payments. When a newspaper report about it appeared, it was deemed Thorpe had infringed the rules regarding amateurism, and in 1913 he was stripped of his titles. In 1983, some 30 years after his death, the International Olympic Committee reinstated his medals at an emotional ceremony attended by two of his children.

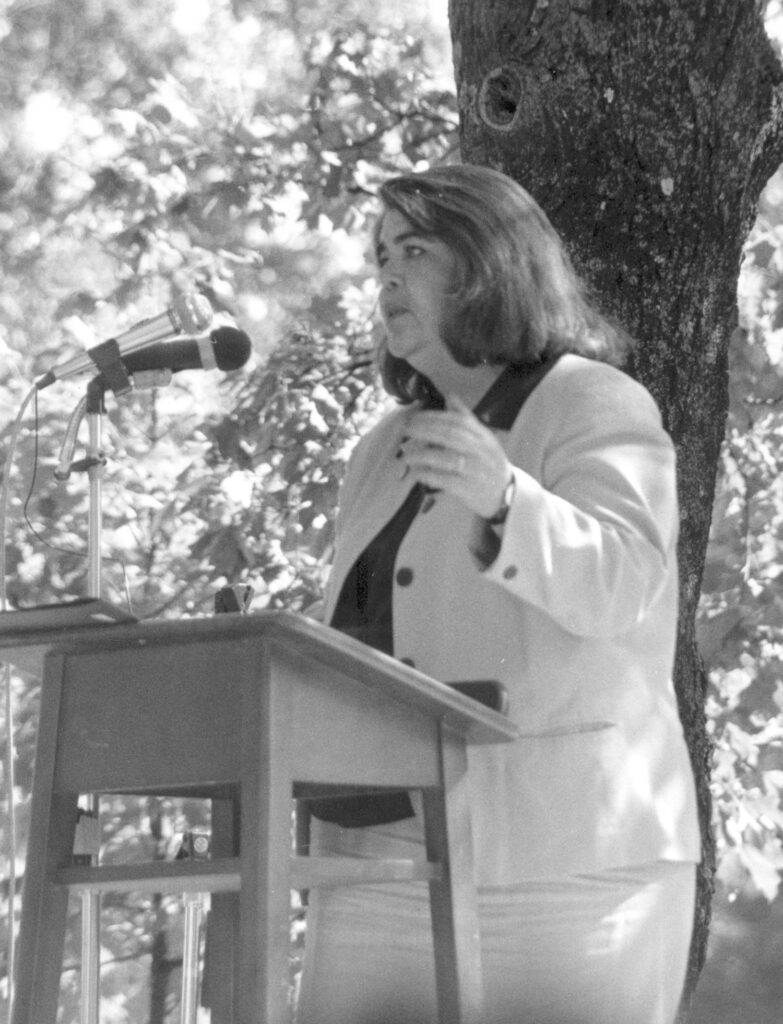

Wilma Mankiller, first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, was also the first woman elected chief of a major Native tribe, according to the National Women’s History Museum. Born in 1945, in Tahlequah, Mankiller moved with her family as a child to San Francisco as part of a Bureau of Indian Affairs’ relocation policy. In a 1993 interview, Mankiller described the move as “my own little Trail of Tears,” a reference to the forced removal of Cherokees to Indian Territory.

Mankiller worked to empower Native communities in California and would bring back that knowledge to Oklahoma. She founded the community development department for the Cherokee Nation, improving access to water and housing. She was elected principal chief in 1985 and led for 10 years. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993, and in 1998 received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Native America’s Profound Impact

The history of Oklahoma’s Native population is typically associated with the Indian Removal Act of 1830, when members of such tribes as the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole were forced to migrate to what was then Indian Territory. But the Osage, Caddo, Pawnee, Wichita, Apache, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, Osage and several other tribes called the region home well before European colonization.

Regardless of when or how they arrived, what the tribes soon had in common was hardship resulting from U.S. government efforts to assimilate them, to take away their traditional forms of government and to undermine their cultures, says Megan Baker, a member of the Choctaw Nation and an assistant professor of anthropology at Northwestern University.

The 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act brought hope and a sea of change. It allowed for tribes to have greater autonomy and assume responsibility for services administered to them by the federal government.

In other words, “self-government was coming back,” says Baker, who spent four years working for her tribe’s cultural preservation department while researching her Ph.D. “They could now govern themselves according to their own kind of culture. They had been taught to be ashamed of their culture. With self-determination they were becoming proud of their culture again.”

Self-determination brought economic development, which Baker witnessed when her family traveled from California to visit relatives in McCurtain County.

“Hochatown is crazy now, but back then there was nothing but forest,” she says. “I watched things pop up here and there. I was really interested in what the tribe was doing, how it was reshaping the area.”

Osage Nation Principal Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear, speaking in March during Sovereignty Day, summed up what self-determination means for his tribe.

“From where I sit, the Nation is doing very well,” Standing Bear said. “We are … getting that Osage back in our lives and I see it and you see it when these little children come and pray for us at our dinners in our own language; and it’s emotional, as it should be.”

Our Emblems

The scissor-tailed flycatcher was adopted in 1951 as the state bird, but it had not been an easy sell to the legislature, what with the bird only hanging around every summer long enough to reproduce.

“The scissortail was eventually chosen for its diet of harmful insects, its Oklahoma-centered nesting range and by the fortunate circumstance that no other state had designated it,” according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

The mistletoe is Oklahoma’s oldest symbol, chosen as the Oklahoma Territory’s floral emblem in 1893. The mistletoe survived its designation when Oklahoma became a state after one senator “passionately orated on the subject, recalling that mistletoe was the only greenery available to decorate graves during the hard winter of 1889.”

In 1986, then-Rep. Kelly Haney wrote legislation naming the Indian blanket as the official wildflower. The new symbol was honored at a ceremony attended by more than 20 tribes. Haney later served in the state senate and as principal chief of the Seminole Nation, and was the creator of “The Guardian” statue that sits atop the state capitol.

The American bison was adopted as the state animal in 1972. The resolution states: “The magnificent animal was native to both the grasslands and woodlands of what is now Oklahoma and was significant in the cultures and ceremonies of many of the Indian tribes who lived in Oklahoma and have passed along their heritage to modern-day Oklahomans.”

The state monument is the Golden Driller, which stands in front of the Tulsa Expo Center. A plaque at the base reads: “Dedicated to the men of the petroleum industry who by their vision and daring have created from God’s abundance a better life for mankind.”

“Labor Omnia Vincit,” Latin for “work conquers all things,” was referred to as a motto in the 1893 statute describing the Grand Seal of the Territory of Oklahoma, according to the OHS.

In 1992, the honeybee became the state insect.

“The honeybee is critical to crop pollination and plays a vital role in our varied and plentiful food supply,” the resolution stated.

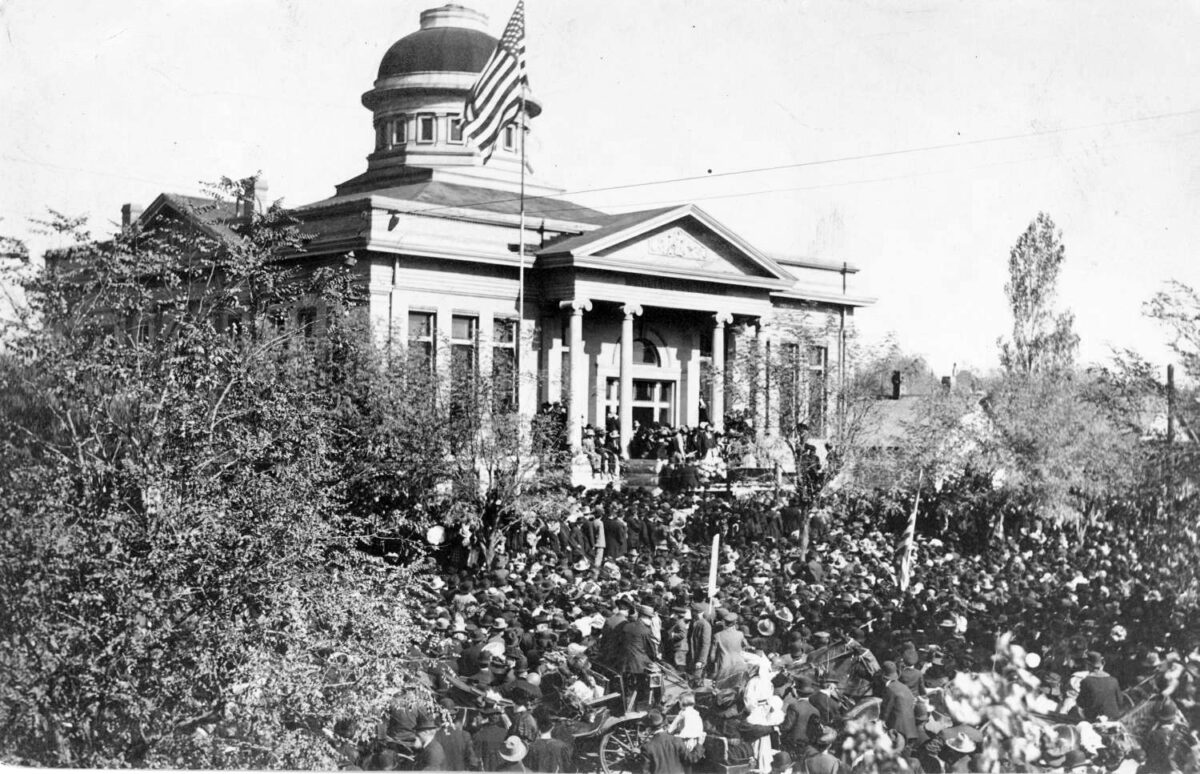

Main image cutline: A scene during the Cherokee Outlet Opening, 1893. Photo courtesy the Oklahoma Historical Society