Ironies abound with Oklahoma’s oldest continuously active military base and its longtime historian.

Fort Sill, just north of Lawton, is the state’s only remaining post constructed during the Indian Wars of the 1800s, according to Towana Spivey, who curated, interpreted and directed its museum from 1982 to 2011.

Oklahoma, today, prides itself on Native culture, but the federal government certainly didn’t make that easy for generations. Spivey, a Chickasaw, descends from the man who suggested the site where Fort Sill would eventually stand in 1869.

“Fort Sill was set up as a control point to give the U.S. military a base of operation against the Plains Indians,” says Spivey, adding with a chuckle, “You could say it’s still going on.”

In 1858, Spivey’s great-great-grandfather Edmund Pickens, a Chickasaw chief operating under a tribal pact with the U.S. government, was a scout for the Army as it dealt with horse and cattle thieves, inter-tribal skirmishes, Natives’ wars against white settlers and ne’er-do-wells, and outlaws from Texas, Spivey says.

“He came out to fight Comanches before there ever was a Fort Sill,” Spivey says of Pickens. “The Chickasaw were administered by the Indian Department [the Bureau of Indian Affairs]. By the time he and his team got to Medicine Bluffs, the Comanche had gone north, not to be found. But Pickens made an official recommendation that a fort be built there – and it was, 11 years later.”

Medicine Bluffs, sacred to Native people for thousands of years, also figured directly into the life of Pickens’ great-great-grandson. While he ran the museum, Spivey testified in 2008-2009 against his employer, the Department of Defense, during a legal battle waged by the Comanche Nation. Fort Sill’s commander at the time wanted a training facility built at the foot of the bluffs on ground that Comanches consider sacrosanct.

The tribe prevailed, and Spivey, under later leadership, helped the facility foster better relations with Native people.

“When I think of Fort Sill, it was special to deal with all the cultural circumstances unique to Oklahoma,” says Spivey, born and raised in Madill and a longtime Duncan resident.

He cites how the facility made an enormous transition as Oklahoma and Indian territories, combined at statehood in 1907, became increasingly populated with whites.

“Around 1900, Fort Sill’s function was dying,” Spivey says, because many issues on the frontier had disappeared.

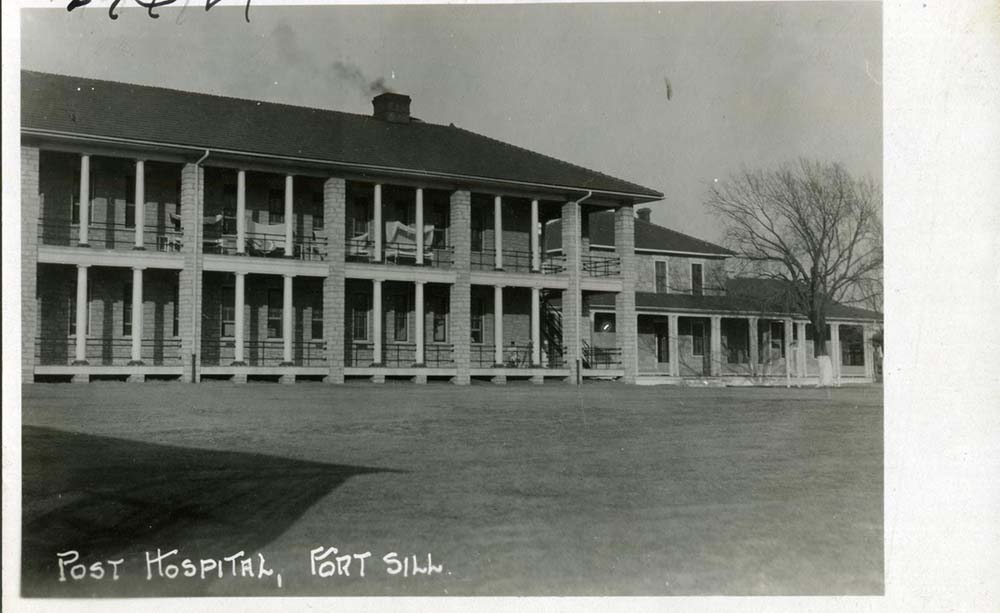

The facility had become a long-term detention center for Native warriors, most notably Geronimo, who’s buried there; the Apache leader and others were allowed to work as uniformed Indian soldiers on the base. Later, Fort Sill held prisoners during World Wars I and II.

“I have personally known and interviewed Apache POWs from the 1886-1914 period, German POWs and Japanese interns from the WWII period, all of whom were kept at Fort Sill – it was a very sad episode in American history,” Spivey says.

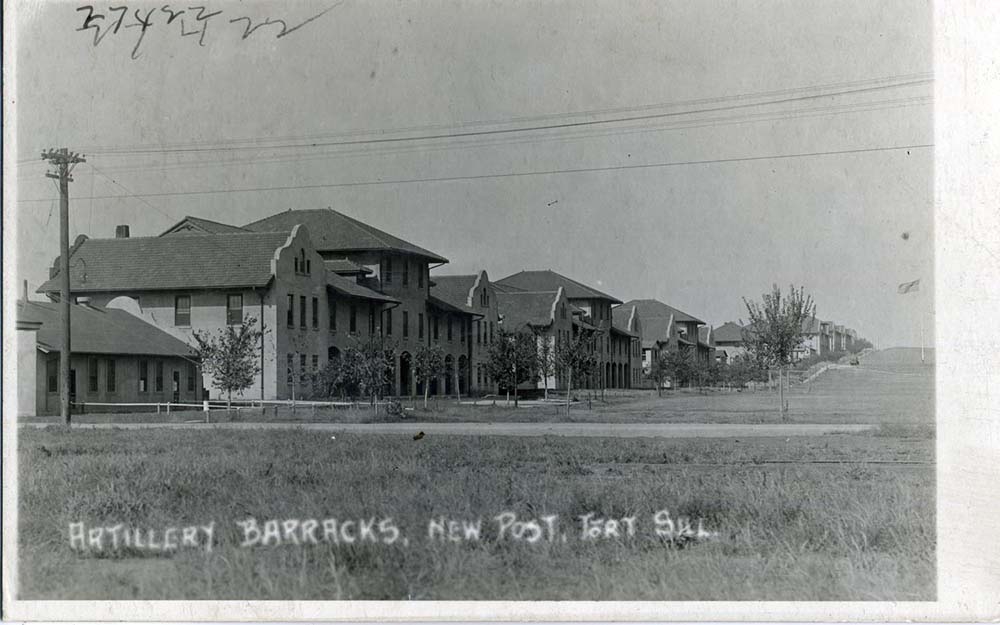

The base ultimately became the Army’s premier facility for field artillery.

“Fort Sill needed a new mission because the world had changed,” Spivey says. “In 1902, the Army put together its first artillery unit, the first one in the country’s history. It started as an experiment to bring them up to speed because of problems they encountered in Cuba and the Philippines during the Spanish-American War.”

By 1910, Fort Sill’s School of Fire was operational. It has received international recognition for more than 100 years.

Spivey, who can talk for hours and hours about Fort Sill’s evolution, hasn’t been back since he retired but his connection to the base remains.

“Some people didn’t like me for saving the Medicine Bluffs,” he says, “but some people saw me as a savior.”

Following is additional information about Fort Sill and Towana Spivey, the facility’s longtime historian.

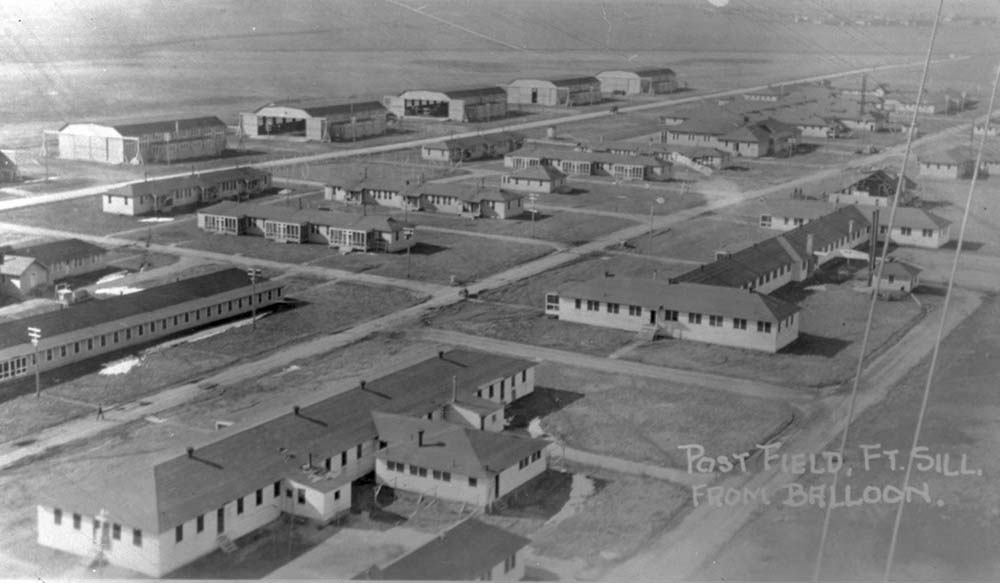

Spivey also notes that Fort Sill formed the world’s first aero squadron in 1915.

“The planes came in crates and were assembled there,” he says. “They didn’t even have an airstrip. They just used flat fields for takeoffs and landings. They flew from Fort Sill to San Antonio – the first squadron flight in aviation history.

“Fort Sill was well-known by that time because many famous officers had served there,” including William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan.

Fort Sill remains Oklahoma’s only surviving military post from the Indian Wars.

“There were others, of course, such as Forts Washita in 1842, Gibson in 1824, Towson in 1824, Reno in 1875 and Supply in 1867, but none is still active today,” Spivey says. “If you are reaching outside the state, there are sites still active, such as Forts Leavenworth, Kansas, built in 1824, Sam Houston and Bliss, Texas in the 1850s, and Huahuaca, Arizona, in the 1860s. All had some role in the Indian Wars, although not as much as Fort Sill.

“Fort Sill was the hub of the so-called Red River War of 1874 and continued to play a major role with the Apache POWs as late as 1914.”

Spivey says the Army, before Oklahoma statehood, often served dual purposes with different parts of the federal government.

“The military could arrest Indians who were later tried in so-called Cowboy Courts,” he says. “The Army could also catch anyone breaking the law and lock them up until the U.S. marshals could come and get them.”

Spivey says Fort Sill and its soldiers even had to deal with the lawless Boomers from Kansas, including leader David Payne.

“It all depends on how you characterize the history,” he says.

Fort Sill’s transition to an artillery base and school came from a suggestion by Col. Dan T. Moore, a top aide to Theodore Roosevelt and the statesman’s sparring partner in the boxing ring.

“In 1910, Moore went to Germany and through their field artillery as they geared up for war,” Spivey says. “He recommended that Americans beef up their artillery because they were behind.”