Vida and Daniel Schuman, Oklahoma Magazine’s publisher and president/editorial director, respectively, have graciously allowed my writing to occupy this space for well over 15 years now. And while that’s maybe been more of a blessing to me than it’s been to readers, I remain deeply grateful to have this platform to, among other things, celebrate some of the people and things in our shared popular culture that I believe should be celebrated, or at least explored and acknowledged.

If you’re a regular reader of this column, you know one of the things I’m kind of crazy about both exploring and celebrating is the musical style that’s become known as the classic Tulsa Sound – even though, after decades of poking around it, talking to those who were there at its genesis, and giving hard listens to music from the era, I still can’t quite pin the term down to my satisfaction. It’s not enough to say that you know it when you hear it; that’s the lazy way out. And I don’t think it’s right to say that it’s a fatuous wrongheaded myth either, a spun-sugar concoction that falls apart every time you try to pick it up.

What I do know is that all the words spilled by those of us trying to get to the core of the Tulsa Sound generally have a kind of elegiac quality, or at least a good whiff of nostalgic homesickness for those good old days of the early ’70s, when, it seemed, Tulsa wasn’t all that different from swinging London, with groovy live music blasting from little clubs and dives spread all over town as the impossibly hip Leon Russell, triumphantly returned from the West Coast, presided over it all and saw that it was good.

What’s missing all too often from reflections on those days – mine as well as others’ – is simply a sense of humor, an appreciation of the absurdity that accompanied the artistry.

Enter Ann Bell.

“A lot of our lives were quite hilarious then,” she says. “Just being around the original Tulsa Sound crew, the founding members – every one of those guys had a really amazing, funny, sense of humor. When bad things would happen – we’d lose a gig, we’d get stiffed for the money, whatever it was – we’d try to find something about it that would just make us start laughing.”

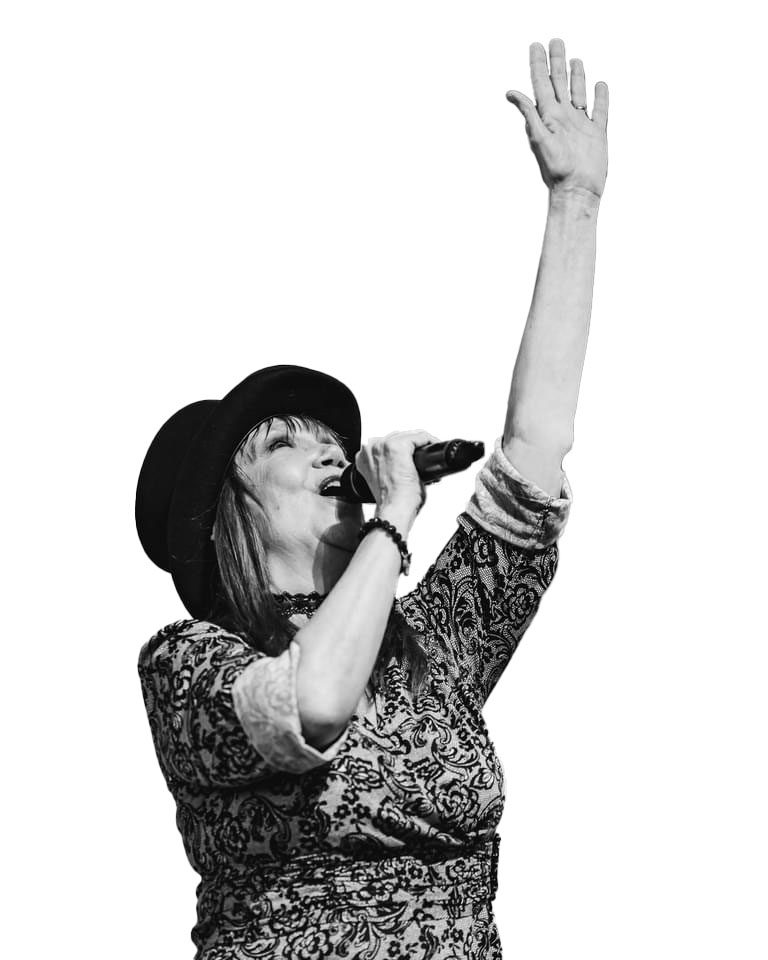

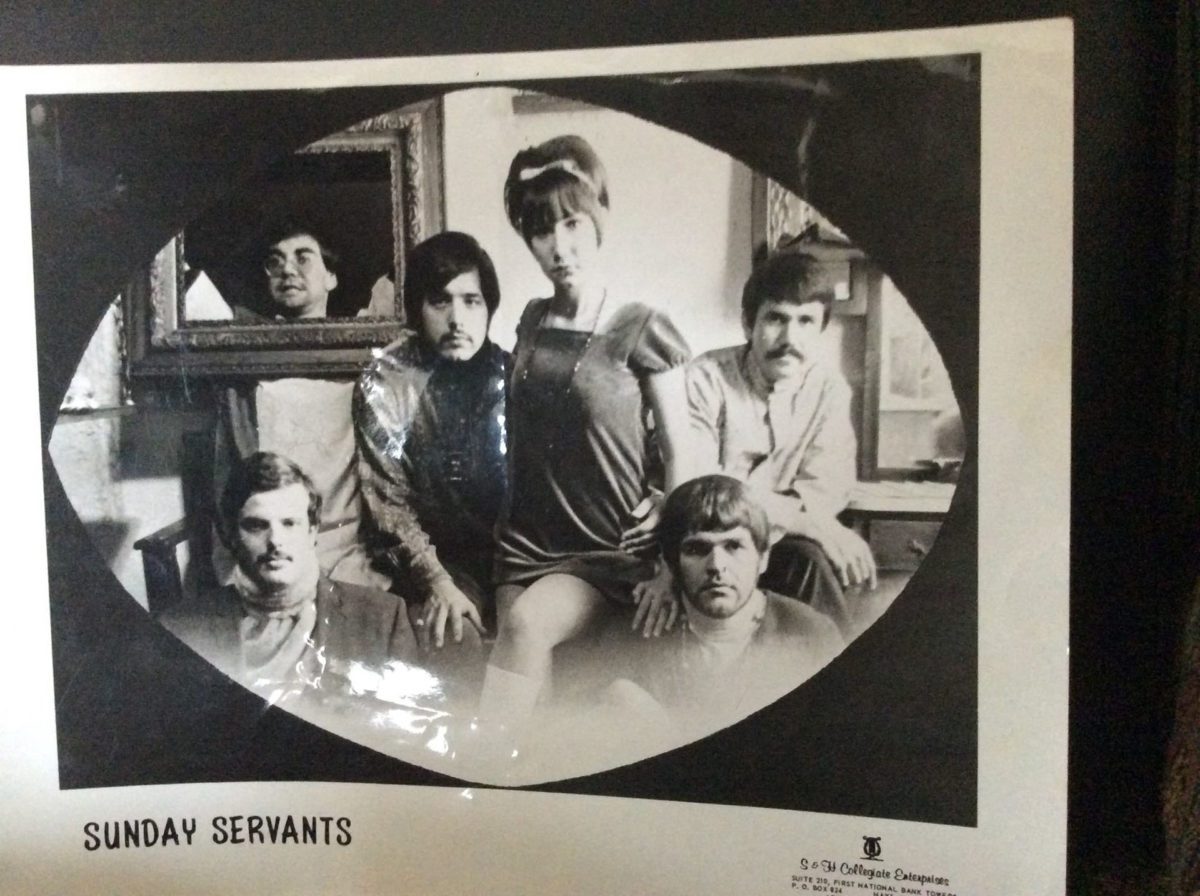

A powerhouse vocalist who joined her first rock ‘n’ roll group, Rubbery Cargoe, while still attending Edison High, Bell went on to be an integral part of Russell’s touring shows in the early ’70s. After four years on the road with him, she spent another five as a part of Joe Cocker’s traveling band. Over the past few years, her hometown profile has risen, or re-risen, dramatically, as she has returned to Tulsa to shine in such events as the Leon Russell tribute concerts at the Will Rogers High School Auditorium and the Women of Song event at the Cain’s Ballroom. She also recently became the latest inductee into the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame, which triggered another well-received Ann Bell stage performance.

As anyone who attended any of those shows knows, Ann Bell not only still has some very impressive vocal chops; she’s also a master at applying the leavening power of humor to what she does, especially with reference to those hazy, halcyon ’70s days. At the Women of Song event, for instance, she asked some of her contemporaries on stage (Don White, Frank Padilla, and Dave Teegarden, if memory serves) if they’d gone out together back then.

“I think we did,” she said to them all. “I’m pretty sure we dated.”

She also prefaced several of her solo numbers with monologues that sometimes called attention to her age and other times gave humorous spins to reminiscences of illegal-substance-fueled events. While her vocals faithfully recalled the power and musical joy of the classic Tulsa Sound days, her words added the lagniappe of humor.

“I never even noticed that’s what I was doing, but over the last few years, people have more and more begun to comment about how they love my stories, because they’re about the rock idols they love so much,” Bell says. “It’s nothing I do consciously. But a while back, I saw a quote from Charlie Chaplin that said, ‘A day without humor is a day wasted.’ So I began to think about that.

“My grandfather was a very funny man,” she adds. “He loved to tell jokes. He loved to play jokes. He loved to make you laugh. I was one of 26 grandchildren, all of whom couldn’t wait to get to his house, because of the funny things that he would do. So I think I inherited his kind of quirky sense of humor.”

As one of those on the music scene when Leon Russell returned to Oklahoma in the early ’70s,

Bell also inherited plenty from the Master of Space and Time.

“He wanted to bring everything he’d learned, I think, from being in [the famous L.A. studio band] the Wrecking Crew and around that part of the industry and those artists, to where the music was headed, all the fields of music, all this stuff,” she explains. “He came to get us, to bring us up to where we were supposed to be. He was our teacher, our inspiration, our bandleader, our father, our business partner. And he was using everyone in his music, whether it was on recordings, doing live shows, or both, but still speaking to us individually about what he saw and the directions where we should be taking our own artistry. He taught us musical perspectives, how to relate to an audience, things to be aware of and cautious of – all kinds of stuff.”

Coupling it with her significant vocal talent, Bell parlayed Russell’s tutelage into a nice long career, which has included fronting her own bands out of Woodstock, New York, where she ended up after the end of the Cocker tour, and working with the likes of Todd Rundgren, Robbie Dupree and the group Orleans (of “You’re Still the One” fame).

Then, she says, “In ’98, I literally walked away from what I would call secular music. I had come back to the church. And primarily, up until about 2013, all I did was church music – mostly Black gospel, but some contemporary Christian.”

In 2000, both she and her husband, keyboardist-producer Tom Nicholson, became ordained ministers, traveling around America and beyond in that capacity. Then, in the mid- 2010’s, she began getting asked to return to Tulsa for what she called “specialty gigs,” usually centering around the classic Tulsa Sound. Those jobs led to her decision to not only perform some secular as well as sacred music, but also to consider a return to Tulsa to live. She says she’s getting ready to do that now.

“I’ll be 72 in December, and I’m thinking I want to do this while I’m still in pretty good shape and I don’t have any health issues, thank you Jesus,” she says. “I just want to come back and plant seeds like Leon did. I want to sow, sow, sow with the players, with up-and-coming players. I want to reset the bar, if possible.

“Not that I’m all that,” she concludes. “But I believe in what I bring, and what I remind my brothers of. When I’m there [in Tulsa], they all say to me, ‘You remind us of what we did, and what it was like.’ We were like Leon’s disciples. We were learning from him, and then we were to apply it, to teach somebody else, and they were to apply it. I don’t want that ever to be forgotten, or not built upon.”