“One hundred years ago,” says Harvey Shell, “most everyone in Tulsa would’ve known Scout Younger’s name. Now, no one does.”

Shell, along with fellow historian Stephen McCartney, are out to change that, hoping to bring a new round of recognition to a man they say was not only a pioneering Oklahoma filmmaker, but a consummate showman and trick rider who, from his Tulsa base, launched his own Wild West show and other attractions all across America. In addition to that, he was one of the city’s early successful businessmen; a piece in the November 19, 1908, Tulsa Democrat newspaper noted that after 12 years in town, Younger was operating “the largest dressed meat and poultry business in Oklahoma.”

According to that story, Younger had been “stranded in a desolate part of Western Texas” when he decided his fortunes might improve if he moved “further east and north.”

“He was an entrepreneur,” explains McCartney, “and he came to Tulsa just as it was waking up from being a quiet frontier hamlet in the Creek Nation. After Glenn Pool [the oil reserve near Tulsa discovered in 1905], the town exploded. And he was there during those formative years.”

Not only was he there; he was making movies.

McCartney found all of this out while he was doing some research on the Dalton family, the one that produced four of America’s most notorious late-19th century outlaws. In the course of his investigations, McCartney came across a couple of interviews done during the 1930s by a writer for the Works Progress Administration’s Oral History Project, a federal government operation that sent people out to gather stories about the country’s earlier days. The writer was Effie S. Jackson, and her field interviews included one with Younger and another with his wife, Pauline, who was separated from him at the time.

“Those got me interested,” notes McCartney. “I started wondering, ‘Who was this fellow?’”

He contacted his friend Shell, and the two of them began digging up whatever they could about Scout and Pauline, looking especially for movies and other entertainment-related work. Among other things, they discovered evidence that the Youngers were the first people in Tulsa to own an actual movie studio, which they operated at 19 North Victor, beginning in 1906. In her WPA interview, Pauline Younger told writer Jackson, “I think we were the first independent movie producers in the United States.”

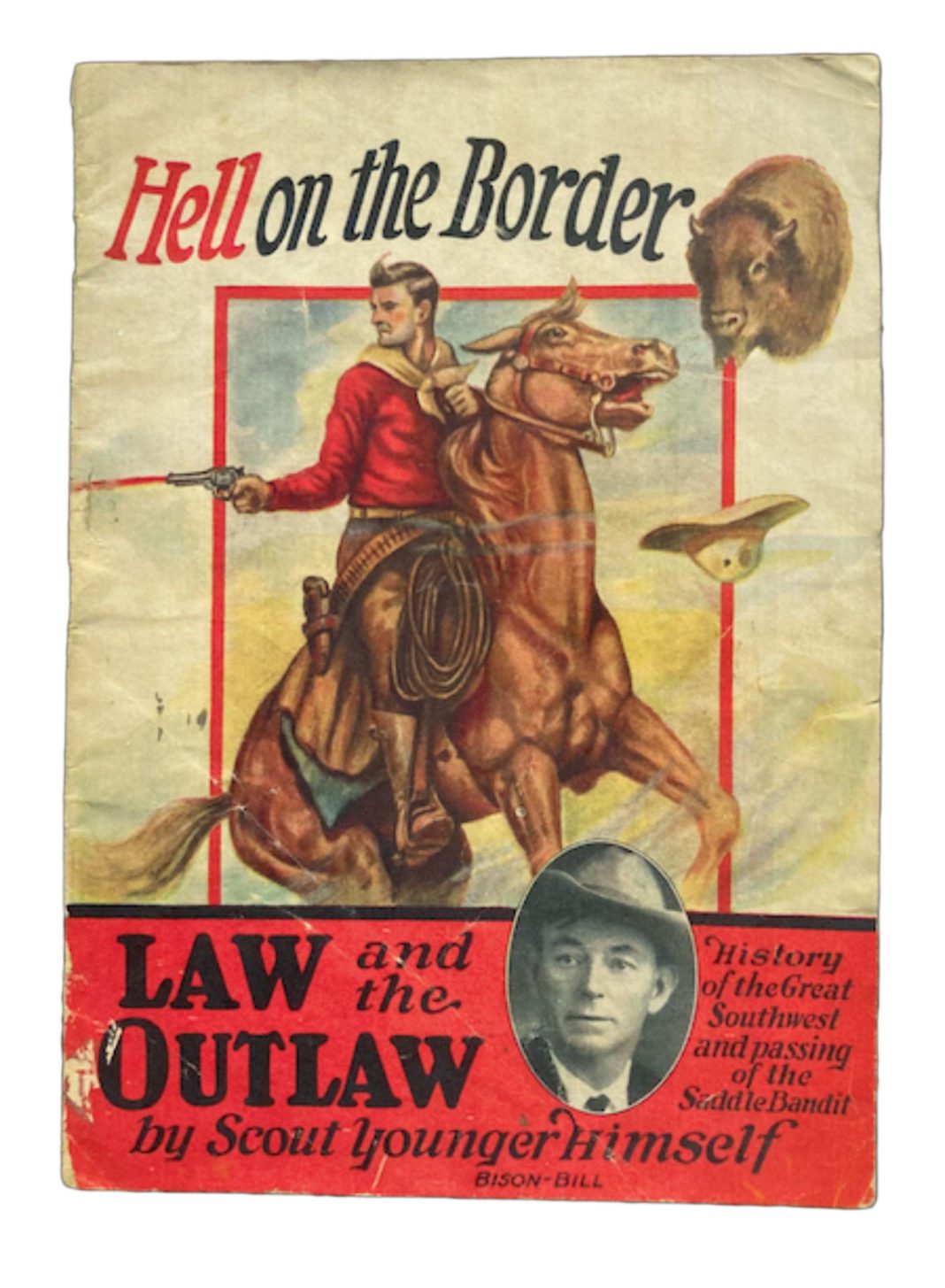

Like most of the other early Oklahoma filmmakers, the Youngers made films about cowboys and outlaws, subjects reflected in the list of productions Pauline Younger shared with her interviewer: Scout Younger on the Western Border, their first, in 1902, which was expanded from the original two-reel version to a four-reeler (with a “reel” running approximately 10 minutes) in 1906; 1907’s Quantrill; 1909’s The Dalton Gang; and later ones, including Bosco (1912), Texas (1913), Belle Starr, and The Younger Brothers. The latter movie starred reformed bandit Cole Younger, from the infamous James-Younger Gang.

And here is as good a place as any to note that Scout Younger and the four brothers in the James-Younger Gang were not related, even though they shared a last name and Scout was sometimes referred to in the media of the day as a nephew or cousin. Pauline Younger told Jackson “There is no direct relationship between Scout Younger and Cole Younger and his brothers,” and McCartney has traced the ancestry of Marcus Jacob Younger – Scout’s given name – back to Scotland, while the outlaw branch of the Youngers had its origins in Germany.

It’s highly unlikely, however, that Scout Younger did anything to quell the assumption that he and the four outlaw Younger brothers were kin. As Shell notes, “Some of Scout’s stories were a little too wild to be acceptable,” including those featured in a long interview that appeared in the November 22, 1913 edition of the Ogden (Utah) Standard, describing how he had ridden with with Jesse James and the James-Dalton Gang.

As McCartney notes, “He would’ve been about eight years old when Jesse James was killed.”

There’s no denying, however, that Scout Younger provided employment to some old-time outlaws – notably Cole Younger and Emmett Dalton – at the ends of their lives, using them as actors and and taking them on tour with the films, where they would talk to crowds about about the advisability of staying on the straight and narrow.

Reflecting on the early days of their filmmaking for the WPA interview, Pauline Younger said, “Of course, it was all simple like those nickelodeons you used to see thirty years ago. We produced our own pictures, then traveled around from town to town in the United States presenting them and giving lectures in connection with them. Our motto was ‘Crime does not pay.’ To prove this, whenever possible, we had the original bandit or outlaw with us and had him tell his own story and draw his own moral from his experience.”

Newspaper ads from the time indicate that Scout did a lot of the lecturing himself for these roadshows. Sometimes, he did even more than that. An ad for the “Pathe 5-Cent Theatre” from the October 8, 1911, edition of the Shawnee (Oklahoma) News, for instance, noted that its engagement of the film Scout Younger on the Texas Border would be “presented by Scout Younger himself who will take tickets during performances.”

At one point, the Youngers also owned their own Tulsa theater, the Subway, between Main Street and Boston Avenue on Second Street.

In her WPA interview, Pauline Younger said that the two of them sold off their movies and got out of that particular business in the early ’20s, going to Chicago and engaging a sculptor named Schmidt to craft a series of wax figures of famous Oklahoma outlaws, which Pauline and Scout then took on the road. Somewhere in there, the two split up, but Scout Younger continued to display the collection for many years afterwards. When the government interviewer Effie S. Jackson caught up with him on August 26, 1937, she found him in the Cowman’s Bar, an establishment he owned at 1440 E. Third St. in Tulsa, surrounded by many of the figures and other memorabilia that she termed “relics of outlawry.”

“To Younger,” she wrote, “this is the end of the trail – his last stand.”

And indeed it was. He died, at the age of 64, only a few months after Jackson’s visit.

Neither McCartney nor Shell has been able to find out what happened to any of the waxworks that were last on public display in Tulsa well over 80 years ago. However, they’re hoping that renewed attention to him and his work might help unearth some of those old effigies.

“He had at least five different sets of them,” notes Shell, “because at one time he had three wax museums around the country, along with two or three traveling exhibits.”

“Maybe there are some of those figures in a basement somewhere,” adds McCartney, “or in someone’s closet.”

But their collective purpose in getting Younger’s name back before the public – or at least before that part of the public interested in Oklahoma history – doesn’t just have to do with unearthing artifacts. They believe that Scout Younger belongs in the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, and that’s one of the main reasons they want to raise public consciousness about him and his work.

“He was a moviemaker and a pioneer and he has been greatly forgotten,” Shell says. “Why he isn’t written up in some of the history books I don’t know. The more you learn about him, the more interesting he becomes.”