To her dying day, my mother could never understand the gravitational-like pull that John Steinbeck’s work exerted on me. As far as she was concerned, he’d taken the name “Okie,” promoted it into a grossly unfair label indicating people of low intelligence and lower class, and then almost personally slapped it on her back and the backs of those around her for the world to see and scorn.

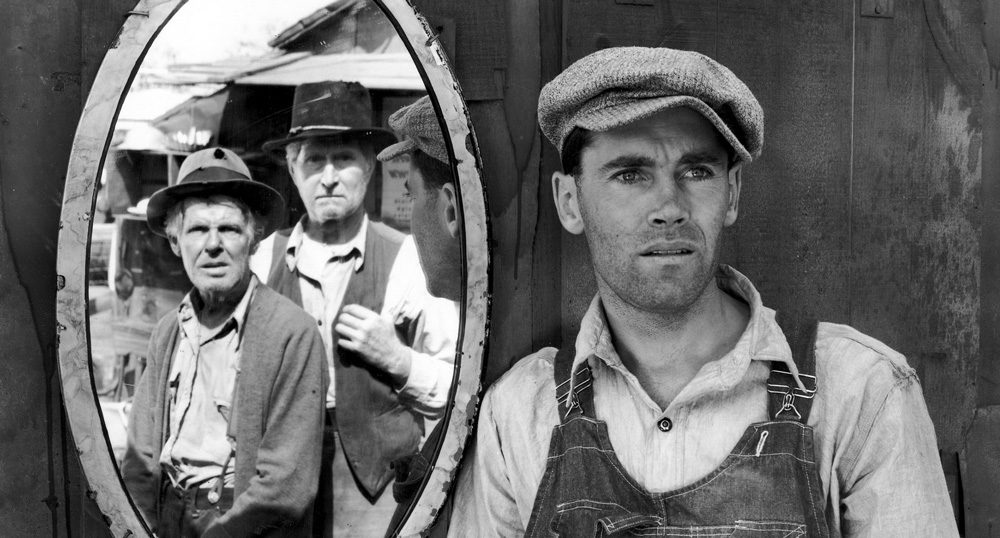

In a sense, she was right. The publication – released 75 years ago – and subsequent success of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath had shown, with relentless clarity, the horrible working and living conditions of the migrant farm workers and others who’d left the middle of America for California in the 1930s (while fiction, it was based on Steinbeck’s own observations). The popularization of “Okie” as a negative term became an unintended consequence of the novel’s runaway popularity.

Steinbeck, however, neither invented it nor made it a pejorative. That distinction goes to a California journalist who appropriated the word to describe a phenomenon he, like Steinbeck, witnessed first-hand. In an entry in the Oklahoma Historical Society’s online Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Carolyn G. Hanneman explains the origin of the label, noting, “In the early twentieth century people from Oklahoma were occasionally nicknamed ‘Okies,’ a special appellation that seemed a natural shortening of the state’s name.”

Then, she adds: “In the 1930s, California newspaper reporter Ben Reddick wrote a series of articles on the movement of farm laborers into California and observed that many came in cars with tags from Oklahoma. Reddick seized the Oklahoma nickname and began to apply it to all migrants. Indeed, the term ‘Okie’ took on the same negativity as a racial or ethnic slur.”

But it was certainly Steinbeck, a native Californian, and his hugely influential bestseller, that planted that slur in many minds. Okies – and, by inference, all Oklahomans – were uneducated, unwashed and unwanted, especially in California, where many of them ended up.

Those migrants from the Midwest, following the time-honored American tradition of heading west for a better life, didn’t have a lot of choices. Their diaspora had its roots in the days just after World War I, when the joyous news of the armistice also signaled the end of some huge markets for crops and meat – both here and abroad – since there were no longer vast numbers of soldiers to be fed by their governments. The grinding down from a wartime to peacetime economy led to a couple of U.S. recessions over the next four years, and farmers found themselves going into debt in order to buy new equipment that would, theoretically, increase the yield of their land and keep their incomes from dropping too precipitously.

Then came Oct. 29, 1929, and the stock market crash that echoed around the world. The Great Depression was on, and soon, in Oklahoma and its surrounding states, so were the drought and gale-force winds of the Dust Bowl.

According to the National Endowment for the Arts’ Reader’s Guide for The Grapes of Wrath, when the westward migrations described in Steinbeck’s book began in earnest, “the Depression unemployment rate was pushing 30 percent, and California entrepreneurs were spreading rumors of better days to the west.”

Unable to grow anything in the ravaged, windblown soil, those whose living came from agriculture – especially tenant farmers like Steinbeck’s Joads, who worked and lived on rented land – became incapable of paying their landlords, often resulting in the seizure of their homes and acreages. Even subsistence farmers were starving.

My mother knew about all of this. Raised in northeastern Oklahoma in the ‘20s and early ‘30s, she and her siblings experienced the Dust Bowl and its privations personally. One of the stories she told concerned her Chelsea High School graduation ceremony in 1934. Like most teen girls of the time, my mother liked to dress sharply, but the only shoes she could afford for graduation were the cheapest the Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog had to offer, and they were adorned with big buckles, which she thought looked hideous. So when the shoes arrived in the mail, she cut the buckles off and tried to make them look like they’d never had any at all.

She said that her family, the Seelys, had been luckier than most, because her dad had a job running an oil lease. That meant he had a steady, if small, paycheck, which was something to be coveted during those Dust Bowl days. Every time the check arrived, he would go to town and buy staples like flour, sugar and lard – and always in duplicate. That was because their next-door neighbors were farmers, and, because of the adverse growing conditions, they couldn’t even raise enough crops to feed themselves. So he would always take them, as a gift, the same load of groceries that he’d bought for his family.

This, of course, is pretty much what Ma Joad does at the makeshift migrant camp in Grapes, when she feeds as many of the starving kids as she can from the meager family stewpot. I used to try to explain that to my mom, to tell her that Steinbeck wasn’t making fun of Oklahomans but showing their character, their values and their determination to work for whatever they got, along with promoting the idea her own father had put into action: Families take care of other families, because we’re all one family. If she’d just look a little deeper, I’d say, she’d see how much the characters in The Grapes of Wrath were like our own people.

She would not look deeper. She would not look at all. John Steinbeck had embarrassed her profoundly, and she would never forgive him.

“Some have said this book exposes a condition and a character of people, but the truth is this book exposes nothing but the total depravity, vulgarity and degraded mentality of the author.” – U.S. Rep. Lyle H. Boren, a democrat from Oklahoma, during the third session of the 76th U.S. Congress in 1940, as published in the Congressional Record.

Yes, there were many Oklahomans besides my mother who hated The Grapes of Wrath – or, at least, hated what they believed it stood for. Congressman Boren, father of University of Oklahoma President David Boren, was himself the son of a tenant farmer, so his vituperation had something to do with the fact that the book struck so close to home. Also – and this is often overlooked – by the time Grapes came out, the worst days of both the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl were over, and Oklahoma farming and ranching were both on the rebound. The conditions that formed the backdrop for Steinbeck’s novel – the same conditions that had driven his Joads and many thousands of real-life families westward – were rapidly becoming better, and some tried to act as if they’d never been as bad as they were.

An editorial cartoon in the Sept. 25, 1941, Daily Oklahoman, for instance, depicted a huge mound of produce with an Oklahoma farmer sitting atop it – “jeering,” wrote Martin Shockley in the January 1944 issue of American Literature, “at a small and anguished Steinbeck holding a copy of The Grapes of Wrath.” The caption read, “Now eat every gol-durn word of it,” conveniently ignoring the fact that the Oklahoma soil from only a few years earlier – the time in which Grapes was set – hardly yielded such a rich bounty.

Still, some did note legitimate inaccuracies in the book. Shockley, in his article “The Reception of Grapes of Wrath in Oklahoma,” quoted several of these commentators, including Houston Ward, then the county agent for Sequoyah County. In a March 16, 1940, interview on Oklahoma City radio station WKY, Ward noted that people in his county were upset with the “obvious errors” in the book, including putting the Sequoyah County seat of Sallisaw “in the Dust Bowl region” (it was just far enough east to escape the designation); “having Grandpa Joad yearning for enough California grapes to squish all over his face when, in reality, Sallisaw is one of the greatest grape growing regions in the nation,” and “making the tractor as the cause of the farmers’ disposition when in reality there are only 40 tractors in all Sequoyah County.”

Ward did add that these inaccuracies made Sequoyah Countians so upset that “they are inclined to overlook the moral lesson the book teaches,” making him one of the few public critics of the book’s accuracy to also acknowledge its value. Most, like Boren, did not.

Others in the state focused their resentment and anger on the entire population of California. A piece from the April 26, 1940, edition of the Stillwater Gazette announced a new group called the Oklahoma’s California Heckler’s Club, organized by employees of Mid-Continent Petroleum Corporation in Tulsa. Creating the motto, “A heckle a day will keep a Californian at bay,” the members intended to “make California take back what she’s been dishing out” by adopting a program that, among other things, would “provide Chamber of Commerce publicity to all Californians who can read.”

Californians, meanwhile, were not all that pleased with Steinbeck’s work, either. The characterization of the state’s major ranchers, farmers and canners as rapacious exploiters of the desperate Okies didn’t sit well with management, especially with the Associated Farmers of California, a powerful anti-union group that started up in 1934, at least in part as a response to the rising tide of migrants. Incensed by the publication of Grapes, the members fought to have Steinbeck retract some of what he’d written. His refusals only angered them more; an idea of the intensity of their feelings against the writer can be seen in an excerpt from the novelist’s letter to his friend, Carlton A. Sheffield, on June 23, 1940. Referring to the Associated Farmers, Steinbeck wrote:

Both Oklahomans and Californians didn’t get any happier in March of 1940, when the movie version of The Grapes of Wrath hit America’s theater screens. There had been some public concern, especially from the Oklahoma Chamber of Commerce, that 20th Century-Fox wanted to film in Oklahoma, thereby adding insult to injury in some minds. In fact, it was mostly filmed in California, although a crew did surreptitiously sneak into the state – claiming to be connected with a picture called Route 66 – and spent a bit of time filming secondary footage along the highway. Very little of that made it into the movie, although the sharp-eyed viewer will spot a few Oklahoma road signs and, in a montage, the Beckham County Courthouse in Sayre.

Although they are separate entities with very different endings, it’s impossible to separate The Grapes of Wrath novel from the film, especially when it comes to the impact both have had on our state. Director John Ford won an Oscar for the picture, as did character actor Jane Darwell, who played Ma Joad; the film’s five other nominations included one for best picture, best lead actor (Henry Fonda as Tom Joad) and best screenplay, for Steinbeck’s friend Johnson.

The movie is credited with inspiring Woody Guthrie to write his series of Dust Bowl ballads, including “Tom Joad,” which makes direct references to the Fonda character and his experiences. Much later, Bruce Springsteen – after hearing “Tom Joad,” reading Grapes and watching the movie – wrote “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” which became the title track of his Grammy Award-winning 1995 album.

The synergy of book and movie doesn’t just motivate great musicians. Over the years, The Grapes of Wrath has continued to exert a profound influence not only on what Oklahoma and Oklahomans mean to the rest of the world, but on the way we in the state feel about ourselves. We’ve spent about three generations trying to come to terms with the word “Okie,” and many of us are still ambivalent about it, even though those who actually lived through the Dust Bowl make up an ever-dwindling demographic.

“I think people view the word a little differently now,” says Karen Neurohr, an associate professor and librarian at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. In 2007, during the Oklahoma Centennial, the OSU Library and Stillwater Public Library were the primary sponsors of a major event called The Big Read, joining with the National Endowment for the Arts to encourage people to read The Grapes of Wrath and attend public discussions and other events centered around the book.

“What I see now in Oklahoma,” she adds, “is how the term ‘Okie’ is embraced and celebrated. It’s on t-shirts, it’s on coffee mugs, it’s something that people are proud of. But back then, the way the term was used was something that was troublesome.”

Perhaps Dewey F. Bartlett helped change those perceptions. Beginning in 1968, our 19th governor made a heroic stab at turning a negative into a positive when he launched a campaign that embraced the word as an acronym for “Oklahoma, Key to Intelligence and Enterprise.” (According to historian Hanneman, the idea actually came from Robert L. Haught, press secretary to Henry Bellmon, whom Bartlett succeeded.) There were gold-colored lapel pins, contests and lots of speeches in which Bartlett would often apply other definitions to OKIE (Oklahoma: Key to Individual Enthusiasm, Key to International Energy, etc.). He designated celebrities like President Richard Nixon, Prince Charles and Andy Griffith honorary Okies. He even petitioned dictionary editors to adjust their definitions of the term.

“The OKIE program brought national and international attention to the Sooner State,” wrote Hanneman, but it all screeched to a halt in 1970, when David Hall was elected Oklahoma governor. Because the new governor did not support the OKIE program, and there was some public opposition to the revival of the word,” Hanneman noted, “the public relations venture ended.”

“By comparison, only 2 percent mentioned the John Steinbeck novel, Grapes of Wrath, or the Dust Bowl that inspired the book. That suggests the old Dust Bowl image of the state is disappearing. That’s good.” – Tulsa World editorial, Feb. 8, 2007

You have to wonder what the results would’ve been if Zogby International had taken its poll (commissioned, incidentally, by the Oklahoma Chamber of Commerce) only in our state instead of nationally. The evaluations for Stillwater’s Big Read program, also from 2007, indicate that a lot more than two percent of Oklahoma’s people still live with the Dust Bowl and The Grapes of Wrath as a cultural memory, even if time has caused the negative images to loosen their hold.

“Most of our participants were in the 55- to-64-year-old range, and most of them had an advanced degree, and they read quite a bit,” says Neurohr. “Some of them did say they remembered how the word ‘Okie’ was used, in a derogatory way, and they still didn’t like the term. But we had a lot more people who weren’t bothered by it than were.

“One person commented that in her house, the word ‘Okie’ was used for those who left, and the people who stayed behind in Oklahoma you would never call ‘Okies.’ I thought that was interesting.”

Of course, some of those who left eventually came back – but many did not. In another way, perhaps they’re still here, still the members of the one big family, the one big soul that underpins Steinbeck’s book.

Back in 1998, the Red Dirt Rangers, that most Oklahoman of bands, played a job in Weedpatch, Calif., site of the government migrant camp where Steinbeck had begun his research for what would become The Grapes of Wrath.

“They decided to have a festival there, and they called it Dust Bowl Days,” recalls Rangers vocalist and mandolinist John Cooper. “Of course, all the adults from that time were long dead, and their kids were in their 70s and 80s. But everyone dressed up in clothing from that era, and there were a couple of old jalopies and stuff like that around.

“We played on a flatbed trailer for several hundred folks, and the first thing that struck me was when we looked out into the audience, and all those faces just looked – familiar. I thought, ‘Boy, I know these people.’ And it didn’t take long before they were asking, ‘Hey, do you know my cousin so-and-so in Watonga?’

“It was an easy camaraderie with that crowd,” he concludes. “Those were our people.”