[dropcap]On[/dropcap] May 18, the Chester Gould-Dick Tracy Museum Facebook page shared the image of a telegram that had been sent to Chester Gould, Tracy’s creator, exactly 71 years earlier.

Referring to a popular Tracy villain, the wire read, “WANT TO CLAIM FLATTOPS BODY LETTER WILL FOLLOW EXPLAINING,” and included a pair of names and a Beaumont, Texas, address.

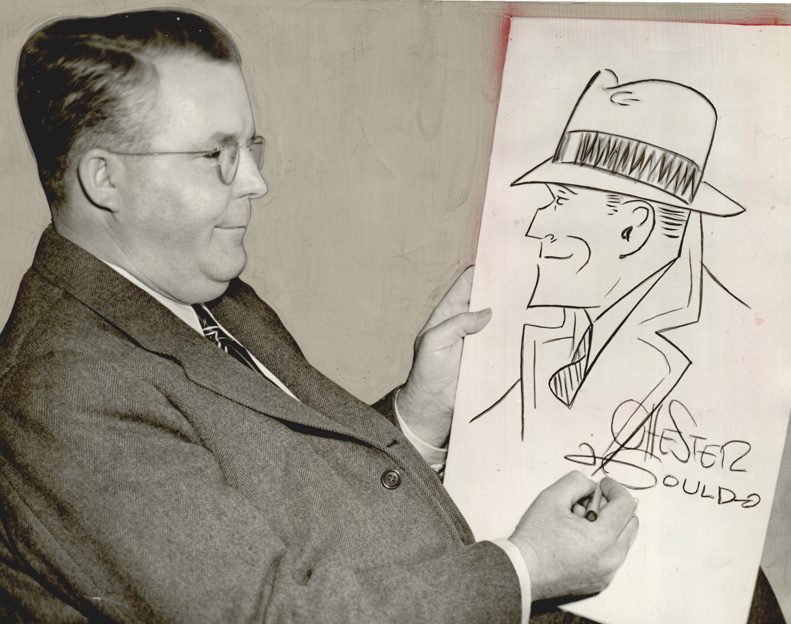

Gould, in a comic strip that ran only a few days before he got the telegram, had killed off the murderous Flattop, one of the scores of bizarre and wildly popular characters the Pawnee native would create during his nearly five decades as Dick Tracy’s creator, artist and writer.

There was, of course, no body to claim. Flattop was a fictional character, a product of Gould’s mind and pen. And while we don’t know any more about the two who were so moved by Flattop’s fictional death that they felt compelled to ask Gould for his remains, we do know that their reaction points up one of the famed cartoonist’s great strengths.

“It just lets you know how real his characters were to people,” says Mike Curtis, who’s been writing Dick Tracy since 2011, 26 years after Gould’s death. “He was very much like Charles Dickens in the way he wrote. Dickens came up with incredible characters, and Gould did the same thing.”

Indeed, for every Uriah Heep, Mr. Bumble, Polly Toodle and even Ebenezer Scrooge put through their literary paces by the renowned 18th-century British novelist, Gould had characters like Vitamin Flintheart, B.O. Plenty, Haf-and-Haf and Gravel Gertie going through their paces in the daily episodes of Dick Tracy’s ongoing saga.

Also, as was the case with the Dickens novels, the Gould characters were wildly popular in their time, their adventures read by untold millions, some of whom saw them as far more than one-dimensional drawings bounded by panels in their newspaper’s comics section.

“When Chester Gould had B.O. Plenty marry Gravel Gertie in Dick Tracy,” wrote Paul McClung in the March 16, 1973, Lawton Constitution, “the couple was flooded with gifts and congratulatory telegrams. Their child, Sparkle Plenty, inspired a doll that produced $3 million in sales in one year.”

The household-name fame of Gould’s characters could cut both ways, however. As writer Jimmie Tramel pointed out in a Tulsa World piece from Oct. 9, 2014, when Gould had the criminous Flattop announce that he was from Oklahoma’s Cookson Hills, the statement “offended both Sallisaw mayor Oscar Capps and Sequoyah County Times owner Wheeler Mayo, who criticized Gould in print:

“Why would a Pawnee boy let one of his bad guys be from Oklahoma?” he wrote.

“I assure [you] there wasn’t the remotest particle of sabotage in my actions,” Gould said in January 1944.” (In fact, Gould’s reference to the Cookson Hills, some 150 miles southeast of Pawnee, was probably a nod to the real-life ‘30s gangster Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd, who had grown up in those hills and, some sources indicate, inspired the Flattop character.)

Perhaps the reason Gould’s characters seemed so real to so many was that their creator viewed them in much the same way.

“Around Christmas of 1949,” says Curtis, “an interview with Gould came out in The Saturday Evening Post, and one of the questions the reporter asked him was, ‘Is Tracy ever going to get married?’ Gould said, ‘No, he doesn’t have time for it. He doesn’t have time to get married. So he never will.’

“Because of the prep time on articles, by the time it came out in the Post, Tracy had eloped with Tess Truehart. So the magazine contacted him again, asking him, ‘What about this?’ And Gould just shook his head, smiled, and said, ‘Tracy never tells me anything.’”