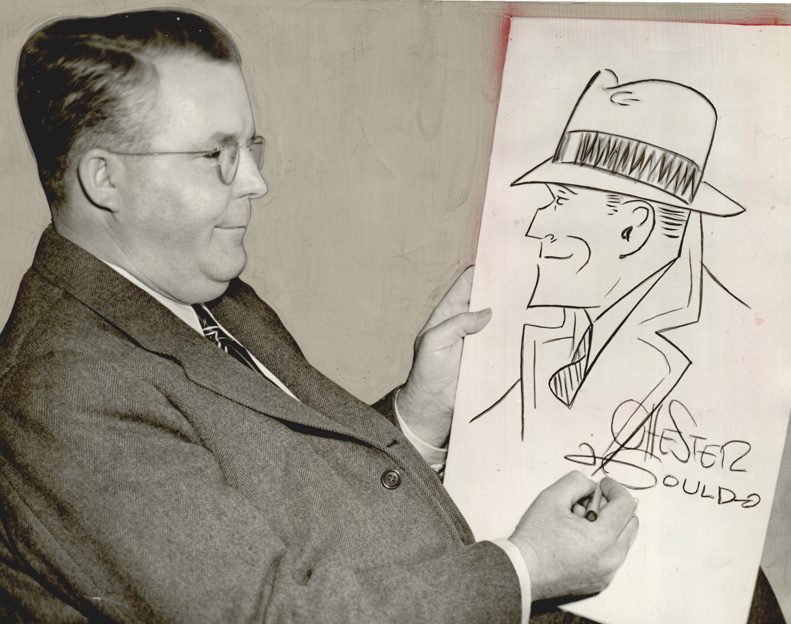

Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

Invention of the Tracer

According to Darrell Gambill, manager of the Pawnee County Historical Society Museum and Dick Tracy Headquarters, Gould was “born in a log cabin out east of Pawnee, outside the city limits.”

On the date of his birth, Nov. 20, 1900, the town of Pawnee was still a part of Indian Territory. The state of Oklahoma didn’t come around until Nov. 16, 1907 – four days before young Chester’s seventh birthday.

By that time, he’d discovered the newspaper comic strip, although “discovered” may be too mild a verb. He was apparently entranced, not only recreating them – notes the Chester Gould-Dick Tracy Museum website – but also “adding in his own dialogue.”

He was encouraged to draw by his father, Gilbert R. Gould, who worked for the local paper, The Pawnee Courier Dispatch. The window of the newspaper’s office proved a fine place to display the budding artist’s work, and it’s likely his course was set when he was 8 years old, and, as the Gould-Dick Tracy Museum site tells us, he was “thrilled when a lawyer on the Supreme Court [bought] a drawing that Chester drew of him” while the man was in town for a countywide Democratic convention.

He was encouraged to draw by his father, Gilbert R. Gould, who worked for the local paper, The Pawnee Courier Dispatch. The window of the newspaper’s office proved a fine place to display the budding artist’s work, and it’s likely his course was set when he was 8 years old, and, as the Gould-Dick Tracy Museum site tells us, he was “thrilled when a lawyer on the Supreme Court [bought] a drawing that Chester drew of him” while the man was in town for a countywide Democratic convention.

What followed for the next few years was a pattern familiar to any young, ambitious creator: contests entered and often won, mail-order study, constant practice. In 1918, his senior year of high school, Gould’s talent was discovered by the yearbook staff at Oklahoma A&M in Stillwater; still in high school, he ended up doing many of the line drawings for their 1918 and 1919 editions. Then in 1919, Gould enrolled at that institution, studying commerce and marketing.

During Gould’s early days on the A&M campus, the oilman-philanthropist Charles Page hired him to draw 18 editorial cartoons for his newspaper, the Tulsa Democrat. Soon, Gould was also cartooning regularly for the sports section of the Daily Oklahoman. These were both paying jobs, but they weren’t nearly enough to satisfy Gould’s artistic ambitions. So, the summer after his sophomore year at Oklahoma A&M, he packed up his portfolio and headed for Chicago.

Why Chicago? Editor Bill Crouch Jr. explained it in the 1990 book Dick Tracy: America’s Most Famous Detective:

[pullquote]This was the first cop, or policeman, adventure story. For that alone, Gould gets into the history books, because nobody else had ever thought of it before.”[/pullquote]“The Chicago Tribune Syndicate headed by Captain Joseph Patterson was the hottest thing in the new burgeoning syndicated cartoon field,” wrote Crouch. “Chester wanted to be where the action was. He arrived in Chicago on Sept. 1, 1921, with $50 cash in his pocket and a suitcase full of samples of his published work in Oklahoma newspapers. Gould would turn 21 on Nov. 20, 1921. The 10-year struggle to become a top syndicated cartoonist had begun.”

During those years, Gould found employment in Chicago’s flourishing newspaper scene. While he wasn’t yet achieving his goal of a nationally syndicated comic strip, he was making a living as an artist, drawing ads and cartoons for, first, the Chicago Journal, a Tribune rival, and then the Chicago Tribune itself, home of the comic-strip syndicate headed by former Army captain Patterson, whose family had founded the paper. But Gould’s employment there had little effect on Patterson, who swatted down every comic-strip idea Gould sent him.

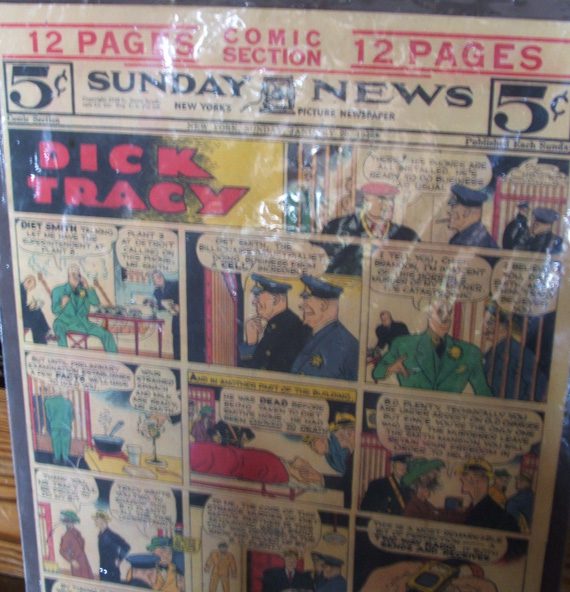

Continuing his education at Northwestern University, Gould graduated in 1923 and was subsequently hired by another Tribune competitor, the Chicago Evening American, part of the newspaper empire of mogul William Randolph Hearst. It was there that he first got a pair of comic strips into print, both concentrating on relatively new forms of entertainment: Fillum Fables was a humor strip with a movie background, while Radio Catts took as its topic was a source of amusement and information for an ever-growing number of Americans. Both were syndicated by Hearst’s King Features, with the former having a decent, if unspectacular, five-year run.

A third strip, The Girl Friends, came into being after Gould had left the Hearst paper for the Chicago Daily News in 1928. As had been the case with the Evening American, he wrote and drew the strip around his other work, including advertising art and editorial cartooning.

All along, Gould continued submitting ideas to Patterson, who was now spending much of his time at the offices of another family-owned publication, the New York Daily News. Patterson just as reliably continued to reject them. A timeline on the Chester Gould-Dick Tracy Museum site claims that Gould shot Patterson exactly 60 unsuccessful pitches for different strips before finally connecting in 1931 with his 61st, an effort called Plainclothes Tracy. (“Tracy” was a play on the word “trace” or “tracer,” which referred to the procedure of tracking down criminals.) As Crouch wrote in Dick Tracy: America’s Most Famous Detective, it was a logical extrapolation of both the area and the era in which Gould lived:

“Chicago and gangsters had become synonymous in the Prohibition era, and Gould thought about the possibilities of a modern Sherlock Holmes set in this period. Gould figured the public, like himself, was fed up with crooked judges, crooked lawyers, hoodlums and gangsterism.”

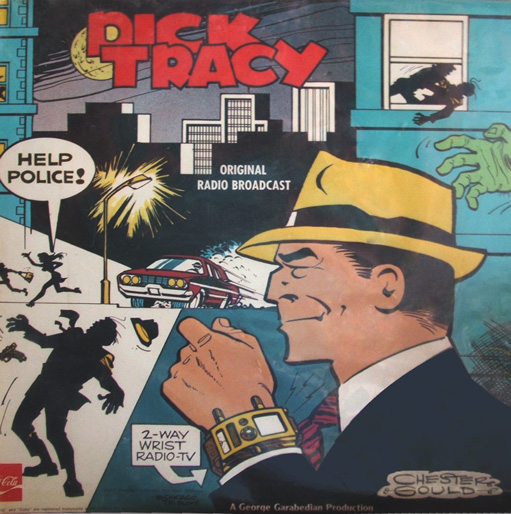

But while it was certainly logical that the city of Al Capone, Bugs Moran and the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre would be the place to give birth to a comic strip about a hardboiled crimefighter, Dick Tracy (changed at Patterson’s suggestion, with “dick” being slang for “detective”) was also an unprecedented achievement – the first strip of its kind.

“There had never been anything like Dick Tracy before,” says Curtis. “They were starting to do story strips [as opposed to the ‘gag-a-day’ humor strip], but they were The Gumps, and Little Orphan Annie, and Wash Tubbs. This was the first cop, or policeman, adventure story. For that alone, Gould gets into the history books, because nobody else had ever thought of it before.”

Back to the Future

“Everybody talks about all the villains Gould created – Flattop, Mumbles, B-B Eyes, and all of them, and that’s great,” says Bart Bush, one of the biggest collectors of Dick Tracy memorabilia in the world. “But one of the things people don’t talk about very much is that he was quite the inventor of things, and his ideas were eventually implemented by law enforcement.”

Bush, who lives in Norman, Okla., cites 1946 as the year that these inventions began appearing in Dick Tracy. There were two of them, he notes: one that didn’t get very far, and another that became very famous.

“He came up with the Atomic Light, a portable device that flashed a white, brilliant beam. Anyone who looked at it was blinded for eight minutes. At about the same time, he created the Two-Way Wrist Radio, which was worn on the wrist like a watch. It had a battery, a microphone and a speaker, and it allowed the user to tune to any wavelength and receive and send messages. Of course, something similar was later actually used by the police.

[pullquote]The police chief in Woodstock decided there should be a real Crime Stoppers club in Woodstock, doing exactly what Tracy, or Gould, wanted done, which was to teach kids about the police force, and what the police do, and why you should stay honest and out of crime.”[/pullquote]“I’ve heard that when Gould came up with that idea, Bell Telephone was working on a concept that was very similar,” Bush adds. “They invited Gould out to their lab so they could show him what they were working on, and as I recall it, theirs had a microphone on the wrist, but you carried the speaker in your front pocket. Gould said, ‘Well, you know, television is coming on, so maybe you guys ought to consider a TV instead of just a radio.’ And they laughed at him and said, ‘Oh no, no, no. It’s hard enough for your readers to believe your two-way wrist radio, much less a two-way wrist TV.’ Of course, in 1964, the two-way wrist TV did show up in the Dick Tracy strip.”

Other Gould inventions Bush cites are 1948’s Teleguard, a forerunner of the surveillance camera, and 1953’s Electronic Telephone Number Pickup, a predecessor to the real world’s caller-ID systems.

“Then, of course, there’s the Magnetic Space Coupe he introduced to the strip in 1962, and in 1968 the Magnetic Air Car, that little thing he rode around in that looked like the bottom half of a capsule,” Bush notes. “Those haven’t come to fruition yet. But they could still happen.”

Perhaps Gould’s most lasting Dick Tracy invention wasn’t actually an invention at all, but a concept that proceeded out of a plot involving Junior Tracy, Dick’s adopted son, and some of his friends.

“There was a storyline in 1947 where Junior and his friends got together to help Tracy solve crimes, and they called themselves the Crime Stoppers,” explains Bush. “It was a detective club of helping hands; its motto was ‘work and win.’ In one episode, Tracy taught them how to photograph fingerprints, and there were other instructional things in the strip.

“Gould was living in Woodstock, Ill., and when he started this storyline the police chief in Woodstock decided there should be a real Crime Stoppers club in Woodstock, doing exactly what Tracy, or Gould, wanted done, which was to teach kids about the police force, and what the police do, and why you should stay honest and out of crime. It was extremely successful and spread to other cities and states.”

Crime Stoppers became Crimestoppers, and by 1949, each Sunday installment of Dick Tracy included a one-panel “Crimestoppers Textbook,” offering tips on combatting illegality. The feature continues in the strip to this day. And while there doesn’t appear to be any official relationship between Gould’s Crimestoppers and the well-known telephone tip line of the same name that offers people both anonymity and rewards for reporting crimes, Bush believes the first Crimestoppers must’ve had something to do with the second.

“I never have really gotten into that,” he says, “but I believe, at least somewhat, it’s all tied back into Chester Gould and Dick Tracy.”