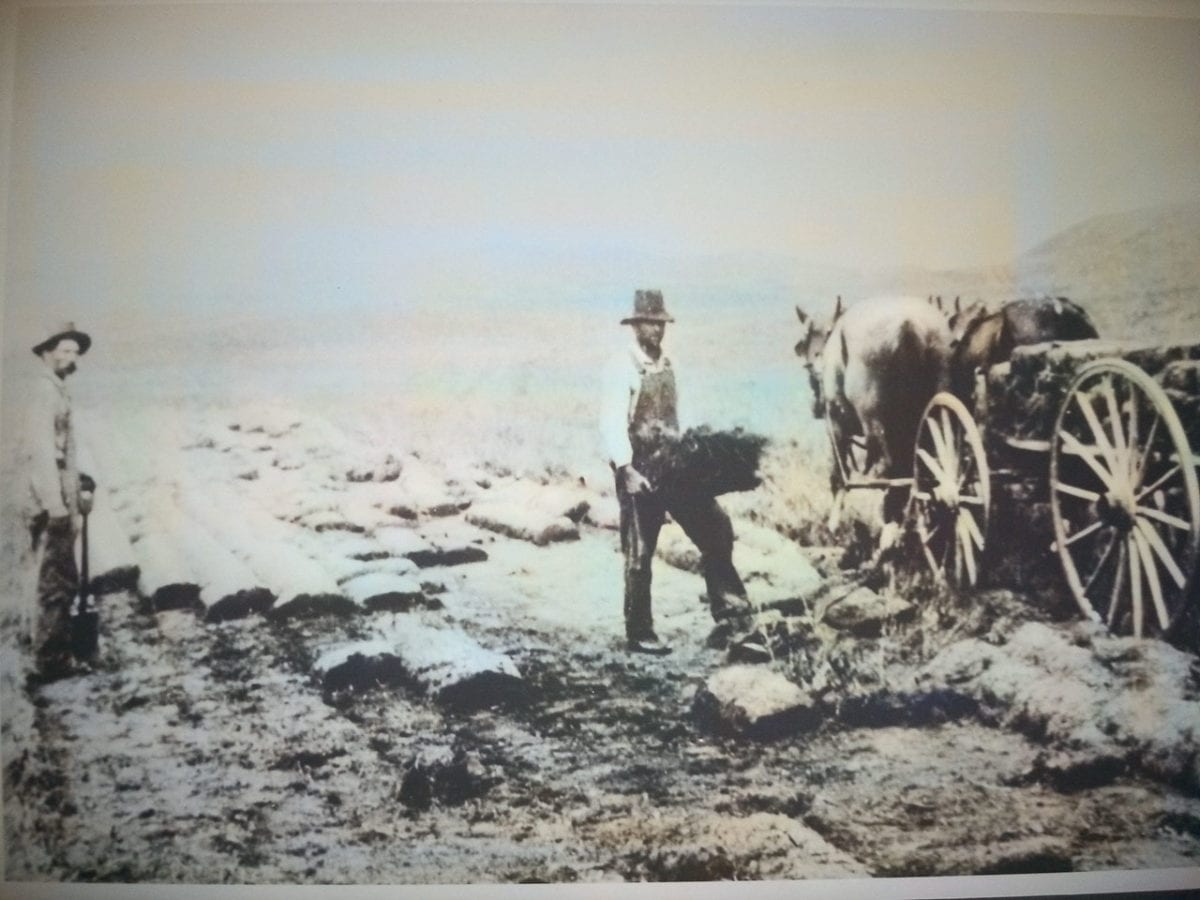

When settlers came to what would become the central portion of Oklahoma, claimed land and started to build lives, they were met with a challenge. The area is primarily prairies and grasslands, with very little timber for building. Thankfully, there were other options. Pioneers in this area, and all through the central United States, built sod houses (or soddies) from the very grassland growing around them.

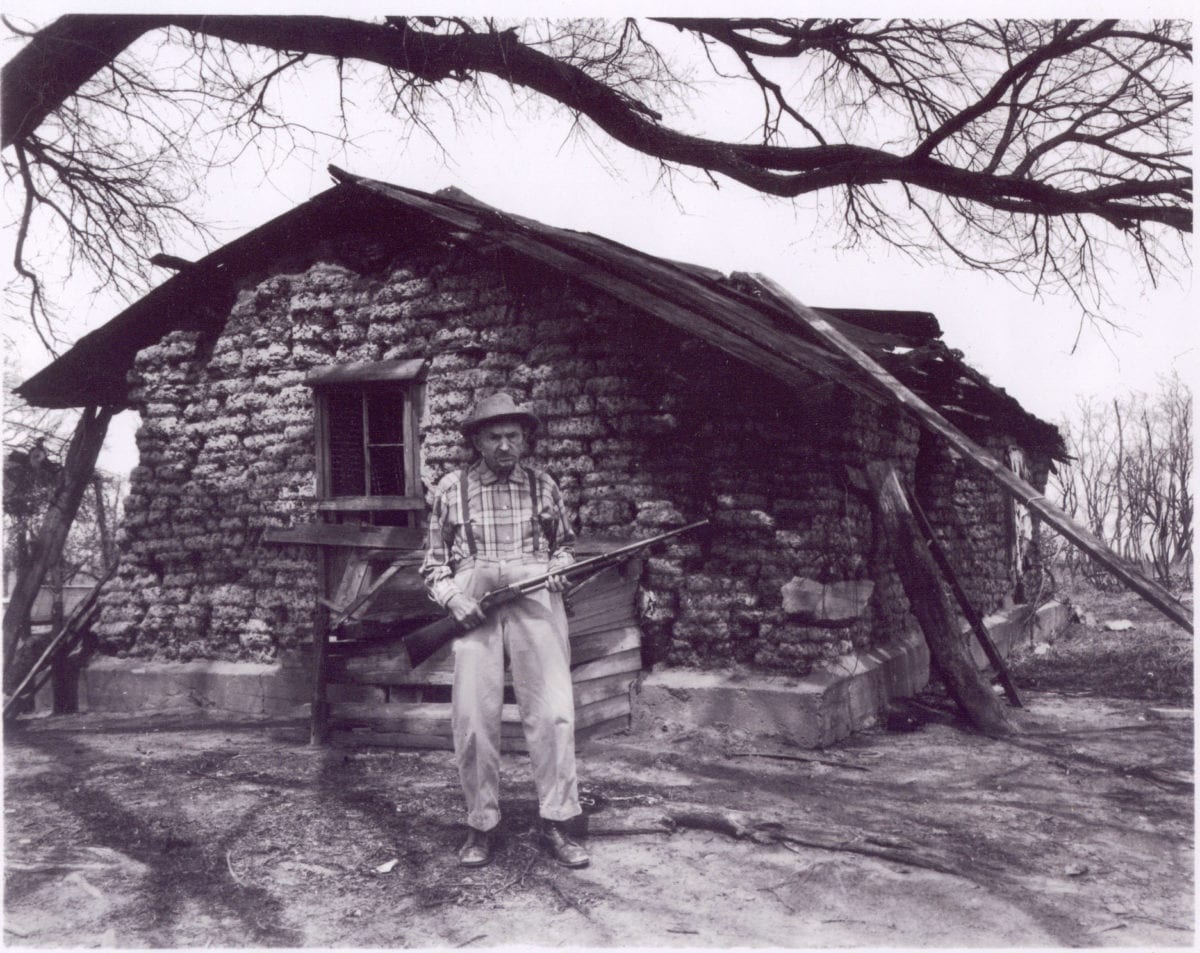

Marshal McCully was one of these settlers. He participated in the land run in 1893, staked his claim and began work on his sod house. McCully’s shelter was especially well-built, and is currently on display at the Sod House Museum in Aline, near Enid.

When McCully arrived for the land run, he had very little to get him started.

“He had a quarter in his pocket and a two-cent stamp, the two-wheeled cart, the horse, some bedding and a tiny bit of food his mother gave to him,” says Renee Trindle, director of the Sod House Museum. But this meager start allowed him to blossom from the prairie around him.

McCully staked his claim in the Cherokee Outlet, but he needed shelter, as he was required to live and improve upon the land. He, and thousands of other settlers, dealt with the lack of timber by cutting the grassy sod into strips, then into blocks that were stacked to make shelters.

According to the Encyclopedia of History and Culture, “typically, [the] soddy’s walls were two to three staggered blocks deep (providing a wall depth of two or three feet), and the sod blocks were laid grassy side down.”

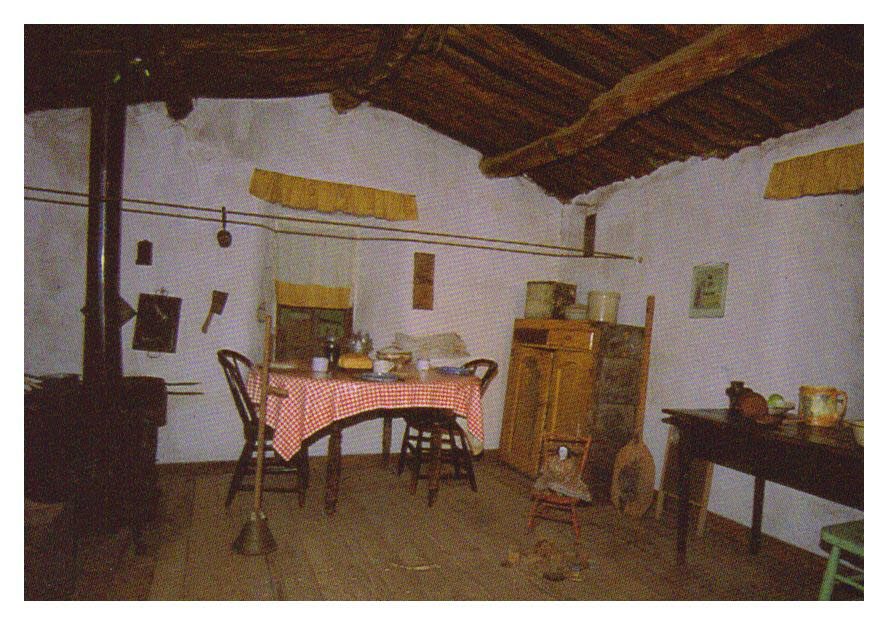

Trindle shares that though simple in nature, the sod house was warm in the winter and cool in the summer, providing natural insulation to keep pioneers comfortable. They were even superior in this respect to the later homes built from timber, as those lacked any kind of insulation.

Photos courtesy the Sod House Museum

For the sod house, the small amount of timber available was used for rafters and frames for doors and windows. McCully recognized the value in the local alkali clay and used it to plaster the inside walls of his structure; one reason it lasted him 15 years and is still standing today. But this was unusual, as sod houses were meant to be short-term housing, typically only sheltering a family for three to eight years.

“When the pioneers wrote their family history, so many of them just wrote tiny bits about [their sod houses] and not details,” says Trindle. The soddy was forgotten once railroads could deliver wood to the area and families were able to construct their permanent homes. But it’s important to remember this part of history.

“People really need to see a sod house to understand this part of the state and how life was,” says Trindle.