A vacation trip prevents drummer Don Hartzell from making a Friday morning gig at Reed Community Center, but the four other musicians who gather in a room at the west Tulsa recreational center every month are loose and jamming by a little after 9 a.m. As kids traipse by on their way to the basketball court, the men sit facing one another, instruments in hand, taking turns calling out tunes that were popular well before any of those passing youngsters were born.

“Let’s try ‘Cab Driver’ in D,” suggests bassist Ed Davison, and in a moment, they’ve launched into the old Mills Brothers standard with the ease and grace of the Queen Mary pulling out of New York Harbor. They’re comfortable playing classic pop, and there’s a good reason for it: Individually, they’ve been making music since the ‘40s.

“They call me the kid of the bunch,” says Davison. “I’m 80.”

Age-wise, the others fall between Davidson and guitarist Lee Oliver, 93, who not only sings and plays solid rhythm, but can also spin out a nice lead when the situation calls for it.

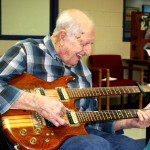

Tom Bordner, behind his accordion, calls the Earl “Fatha” Hines evergreen tune “Rosetta,” and Oliver and Davison leaf through big folders of chord and lyric sheets on the stands in front of them. Beanie Fraley, playing a double-neck guitar (12-string above, six-string below), has no need for a music stand; glaucoma robbed him of his sight a dozen years ago.

The four begin “Rosetta,” which was also a favorite of western-swing king Bob Wills. It sounds more Wills than Hines, which is appropriate, since 89-year-old Fraley is one of the last men standing who played, albeit briefly, in one of the golden-age western-swing groups led by a Wills brother.

Fraley would’ve been somewhere around 10 years old when Bob Wills led his ragtag bunch of musicians out of Texas and through Oklahoma City to Tulsa, launching from T-Town a new sound that would make its way across much of America and beyond. At its base was the kind of fiddle music Wills and his father and grandfather had played for ranch house dances; by the time he got through with it, however, you could hardly find a musical style that it didn’t contain.

As western swing grew and spread throughout the ‘30s and ‘40s, other bandleaders came along to get a piece of the action, including Leon McAuliffe, Wills’ one-time steel guitar player. Wills encouraged his three younger brothers to front their own bands, and they did, giving the music world Johnnie Lee Wills and His Boys, Luke Wills’ Rhythm Busters and Billy Jack Wills’ Western Swing Band. Although Johnnie Lee would stick close to Tulsa, the others would emulate their big brother and work throughout the west and southwest.

It was with Luke Wills, then based in Fresno, Calif., that Fraley made his mark – if only briefly.

“It must’ve been about ‘47 that Luke made the trip out here [to Tulsa] and toured back to Fresno,” Fraley says. “[Guitarist] Junior Barnard had made the tour back here with him, but Junior didn’t want to go back. They put the word out that they were looking for a guitar player. So I was able to tour with Luke.

“It didn’t last a long time – at least a couple of weeks, I’d guess. But some eventful things happened on that trip. Bob Wills had loaned Luke his ‘41 Cadillac Town Car. Billy Jack had just bought a new Plymouth, and he’d loaned it to Luke; and those two cars were what was making the trip, one of ‘em hauling the trailer. Well, the fan that cools the engine went out on that Cadillac up in Burley, Idaho, and we couldn’t find nothing to fix it with. So they put a block of wood under the hood and tied the hood down and drove that Cadillac all the way back to Fresno,” Fraley says. He laughs. “I imagine that engine was shot by the time it got back there.”

Once they got to Fresno, he remembers, Luke Wills dismissed him from the band, “and it seems like the other guys were let out, too. So I went up to Merced (California) and played in a place called Blue’s Rainbow Club. It was just a part-time job. The singer there was Curly Lloyd. As Jack Lloyd, he went on to play [and sing] with Bob Wills.”

Luke Wills wasn’t the only western-swing bandleader to share a stage with Fraley. Right before going on the road with Luke, Fraley spent a little time with the Tulsa-based McAuliffe and his jazz-influenced group.

“I auditioned for him down at the Musicians’ Union Hall, right here in Tulsa,” he recalls. “Leon, he made a comment about me being able to play inverted chords; he must’ve thought I had more music theory than what I did.”

He laughs again. “He hired me, but I wasn’t able to stay. They read arrangements and stuff, a lot of charts, so I was only with Leon about a month or so.”

That gig may have been foreshadowed several years earlier, when a young Fraley was forced to spend six months in a sanitarium in Talihina, following his exposure to tuberculosis.

“I was 14 years old,” he says. “My bronchial tubes were infected – praise God, I didn’t have anything in my lungs. But while I was there, Leon McAuliffe came there to see his first wife. I think she passed away down there, a little later. I picked up my first guitar while I was there, and seven years later, I was playing in his band.”

From then on, Fraley only put his guitar down once for any extended period of time – from 1967 to ‘75, while he was working for an appliance delivery service in Tulsa. Once he picked it back up, however, he began developing a new way of tuning and stringing a 12-string guitar. His experimentation led to a story in Guitar Player magazine’s October 1983 issue.

“I got letters from guitar players all over the world – Taiwan, England, South America, Canada. I’d written an instruction book the best I could with my limited theory, and I sold quite a few of ‘em. I was in the process of resurrecting it for the Internet when I lost my eyesight,” Fraley says.

He still plans to make the technique he calls Twelve-String Magic available on the web.

Fraley’s 12-string magic weaves its spell particularly well this Friday morning on Duke Ellington’s moody “(In My) Solitude,” the others joining in to create a sound that recalls the cocktail-jazz of accordionist Art Van Damme. It’s one of many jazz and pop tunes the jammers do, sometimes led by Fraley’s vocalist wife, Imogene.

Fraley explains that they used to play more country, but the singer who brought in most of those songs recently passed away.

Time and the Reaper have indeed claimed many of the jammers over the years, including steel-guitarist Buster Magness, Fraley’s longtime friend who recorded and played with Johnnie Lee Wills, and Oklahoma City-based western-swinger Merl Lindsay. In the beginning – and no one’s quite sure when that was – it was a big group that played in conjunction with a breakfast at the center.

That was some time ago, though. This morning, it’s just these four men and Imogene, filling up the little room off the hallway, joking with one another, singing the familiar tunes and fingering the familiar chords. There may not be many of them left, but they play on, and their music does not die.