“Sickle cell is the most common inherited blood disorder in the United States, affecting an estimated 100,000 Americans,” says Ashley Baker, M.D., interim director of the Pediatric Sickle Cell Program at Oklahoma Children’s Hospital OU Health, as well as the associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences in OKC.

There are variations of sickle cell disease, she says, and Hb SS – also known as sickle cell anemia – is the most common form.

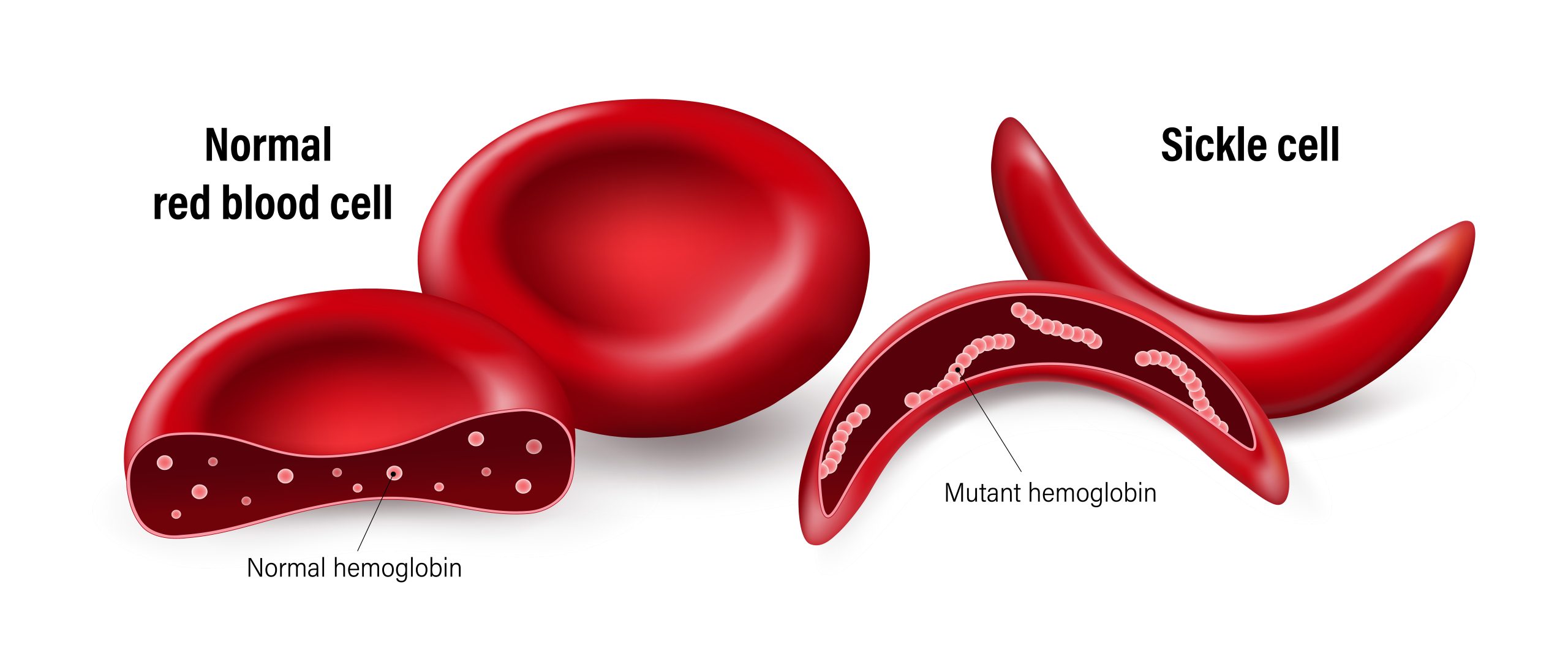

“It’s caused by a mutation in the beta globin gene, which is responsible for making hemoglobin,” says Baker. “Hemoglobin is the protein in red blood cells which carries oxygen to all parts of the body. The abnormal hemoglobin causes the red blood cells to be rigid and shaped like a C, or sickle. Sickle cells can get stuck in blood vessels (vaso-occlusion) and block blood flow. Vaso-occlusion can cause intense pain, stroke, pneumonia and other organ damage, and vaso-occlusion in the spleen increases the risk of life-threatening infections. Sickle cells also break down faster than normal red blood cells, leading to anemia.”

Regarding the genetic component, Baker says a child gets sickle cell disease when he or she receives two sickle cell genes – one from each parent. In addition, she says sickle cell disease is more common in certain ethnic groups including people of African descent, Hispanic-Americans, and people of Middle Eastern, Asian, Indian and Mediterranean descent – though all ethnicities are affected.

“Sickle cell disease is diagnosed at birth by the newborn screen, mandatory in all states,” she says. “It can also be identified prenatally. Affected infants may not have symptoms until five or six months of age. Adults born prior to universal screening or outside of the United States may be unaware of their diagnosis if they only have mild symptoms.”

For those living with sickle cell disease, treatment plans can be complex and require consistent medical supervision to help relieve pain, prevent infection and minimize organ damage.

“Life threatening infections can be reduced through use of prophylactic penicillin, routine childhood immunizations and immediate evaluations for fever,” says Baker.

In addition, she says Hydroxyurea, a medication approved by the FDA in 1998, reduces the rates of pain, hospitalizations, pneumonia, stroke and anemia, and prevents or slows down organ damage. Newer FDA-approved medications include voxelotor, L-glutamine and crizanlizumab – and in 2023, the FDA approved two new gene therapies “to provide very effective disease-modifying treatment that may be life-changing,” says Baker.

While research continues, at this time the only potential cure for sickle cell anemia is through a bone marrow transplant – but with the need for finding a genetic match and the risks and complications involved with a transplant, the potential for this course of treatment varies by individual.

“Sickle cell disease is a chronic, debilitating, life-threatening blood disorder that has a higher risk of early mortality,” says Baker. “At Oklahoma Children’s Hospital OU Health, we have a comprehensive team including physicians, nurse practitioners, social workers, nursing and psychologists to provide care to approximately 200 children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Our goal is to prevent and treat medical complications and improve quality of life for this unique group of patients following national guidelines and standards of care.”

![AdobeStock_554881676 [Converted]](https://b1523572.smushcdn.com/1523572/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/AdobeStock_554881676-Converted.jpg?lossy=1&strip=0&webp=1)