Christopher Lewis was a true child of Hollywood. His father, Tom, made his mark as a radio-entertainment pioneer and film producer; his mother, Loretta Young, reigned as one of the very biggest stars of Tinseltown’s Golden Age, on her way to becoming a 1950s television icon. Over the past several decades, Chris and his wife, Linda, had spent most of their time living around his native L.A., as well as in Arkansas and Florida. They were wintering in the latter state on Jan. 28 when Christopher died from heart issues. He was 76.

Although Hollywood was his home, Chris Lewis, beginning in the early ’80s, lived and worked in Tulsa for a good long stretch – and, interestingly enough, it was in Tulsa, not L.A., that he and Linda left their most lasting mark on the entertainment business. Shooting their first feature when the notion of creating movies solely for home video (as opposed to theatrical and/or TV distribution) was brand-new, they became two of the very first filmmakers in the world to show not only the feasibility of that revolutionary idea, but its profitability as well.

“Christopher would be enjoying the news that emerged recently about Oklahoma becoming more and more of a film center,” says Michael Wallis, a writer, actor and filmmaker who collaborated with the Lewises and his own wife, Suzanne, on several documentary projects. “He was a part of that. I think he should be considered one of the pioneers of modern filmmaking in Oklahoma.”

As was the case with Michael and Suzanne Wallis, my relationship with Chris and Linda was a long and fruitful one. It began when Chris, then a local TV anchorman, interviewed me about a book I’d just put together, which collected stories about a pulp-magazine character from a bygone era named Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective (as written by a 1920s Tulsa Tribune employee named Robert Leslie Bellem). Chris and I hit it off, and after reading the book, he was sufficiently intrigued to offer an option, which meant that he gave me some money in return for having exclusive rights to make a movie out of it during a certain period of time. He told me that he and Linda were looking into producing some movies for the Tulsa-based VCI, one of the biggest of the independent videocassette distributors.

Even though I was a relative newcomer to the book scene, I knew that the chances of an option ever leading to a real movie were miniscule. But I happily took the money and went on about my business – which, at the time, included writing entertainment for the Tulsa World.

It was in that capacity, not all that long after our TV interview, that I found myself on the Cascia Hall campus in Tulsa, watching Chris direct a scene from what would turn out to be a trailblazing horror movie, Blood Cult.

“Actually, I attempt to direct,” he told me for my on-the-scene story that appeared in the March 15, 1985 World. “When you do ‘em fast like this, what you do is keep things moving, keep doing a lot of things quickly.”

He and Linda, who produced the picture, indeed kept things moving, with major assistance from VCI owner Bill Blair, who’d co-written the script. Shot in nine days with a total crew of nine and cast of around 20, Blood Cult was ready to go by June 27, when it had its invitation-only premiere in the Arizona Room of the Doubletree Hotel at Warren Place in Tulsa. VCI then put it on sale internationally, billing it as “the first feature-length motion picture made especially for the home-video market.”

Of course, tracking down the “first” of anything is always difficult, and before Blood Cult there had been other movies that had gone directly to home video. However, most of these were films that hadn’t been able, usually for reasons of quality, to get a theatrical release, and their backers had subsequently dumped them onto the videocassette market to cut their losses. Blood Cult was one of the very first – if not the first – of the films aimed intentionally toward home video to show a significant profit. In doing so, it ignited a direct-to-video feature-film boom that spread across the country and the world. In only a few months, a plethora of other distributors and moviemakers had jumped into that particular pool, and very soon, scores of movies glutted the home-video marketplace. VCI and the Lewises turned out two more horror features together, The Ripper (also 1985) and Revenge (1986), before parting ways.

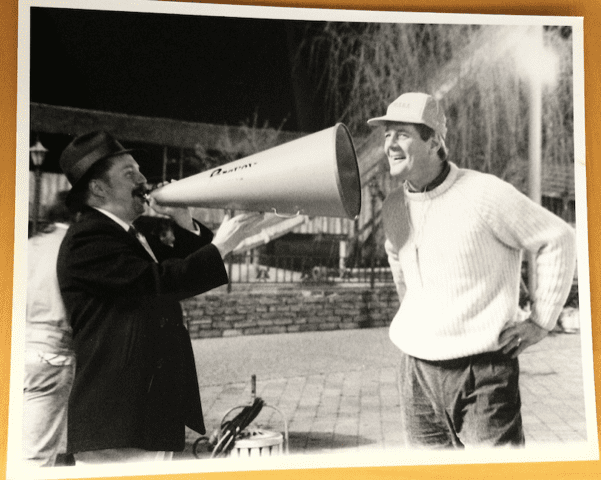

John Wooley (left) is seen here in costume with Chris Lewis for an extra role in Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective.

A couple of years later, Chris and Linda were in Nashville, co-hosting the TNN TV series Side by Side. After that show ended, they returned to Tulsa to shoot a made-for-TV movie for the LBS network, which supplied programming for hundreds of independent stations across the country, including Chicago’s WGN, New York’s WPIX and Los Angeles’s KTLA.

The film? It was an adaptation of one of the stories from the book Chris had optioned from me years earlier, featuring the old pulp-magazine detective Dan Turner. And they asked me to write the script. So I went from covering Chris’ movies to working with him and Linda, an experience that’s echoed by what Michael Wallis remembers about his own time with Chris.

“My memory of him is this great big guy with a smile on his face, just moving forward,” Wallis remembers. “How easy was it to work for him? It was very easy. He was not temperamental. He was certainly not a negative person. He was good to work with, because he’d listen if you had an idea. He was a very compatible guy.”

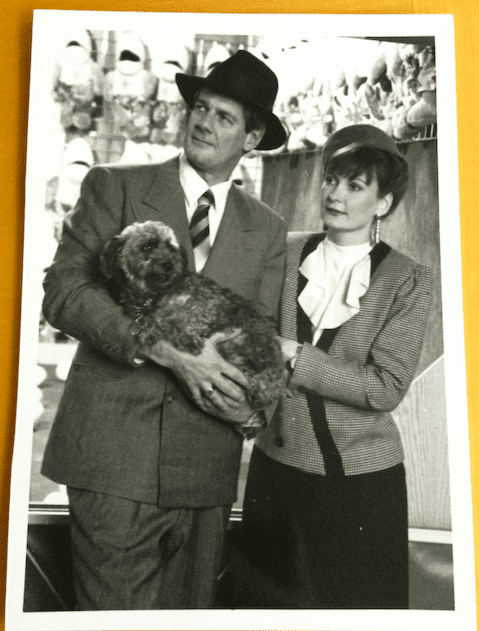

For 1990’s Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective (released on video as The Raven Red Kiss-Off), Chris and Linda got to work with a higher budget and a bigger roster of stars than they’d ever had before, including lead Marc Singer of V and Beastmaster fame. Still, even with the added pressure that always comes with more money and increased studio oversight, Chris remained unflaggingly – as Wallis puts it – compatible.

Following the release of Dan Turner, the Lewises concentrated on making documentaries; like Michael and Suzanne Wallis, I was privileged to work on several of them. Periodically, Christopher would make a Dan Turner presentation to a studio or producer, always including me as the writer; a couple of times we came close to relaunching the character, but never quite got the green light.

Still, Chris hung in there. Several months before his death, he had worked up a new, detailed proposal for a Dan Turner series, and he recently emailed me that his new production company was called Paravox Studios – the same name as the fictional film company in Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective. He always signed his emails “Bernie,” the first name of the Paravox executive in our movie, addressing me as “Pedro,” for Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective’s gambling-house proprietor (played by former Laugh-In star Arte Johnson). At the same time, recalls Michael Wallis, he and Chris were also talking seriously about future movie projects. (Reflecting Chris’s penchant for nicknames, they referred to one another as Ernest, for writer Hemingway, and Otto, for director Preminger.)

In his septuagenarian years, Christopher Lewis had every right to feel that he’d done enough in the business. As one of the first filmmakers to show the world that movies didn’t have to be exhibited in theaters to turn a profit, he’d been in the forefront of a huge development in motion-picture history. In addition, he’d continued to explore a variety of subjects, including his love of trains, in documentaries that were watched by uncounted eyes on television stations, videocassettes and DVDs. Yet, for all of that, Christopher Lewis kept on doing what he did, kept on pitching, kept on trying.

It took the silencing of his heart to stop him.