Just a couple of blocks off Oklahoma 66, down Pine Street in Catoosa, sits the D.W. Correll Museum, an incredible repository of rocks, minerals, fossils, antique cars and carriages, jewelry, bottles and decanters, toys, model ships and autos – and more. There’s so much, in fact, that the collection takes up two buildings.

At every turn, you’ll find something intriguing. Among the major attractions is a room featuring a big display of florescent minerals, which change colors when they’re bathed in ultraviolet light; a fossil plate from Morocco, dominated by remains of the ancient creatures known as ammonites; and a collection of horse-drawn carriages and automobiles, two of which were recently borrowed for the filming of Killers of the Flower Moon.

But for all of that, my favorite exhibit in the whole museum turned out to be something a bit, well, weirder: a mummified cat in a display box. Museum director and curator Eric Hamshar calls the long-defunct animal “Fluffy,” although it’s anything but.

“Fluffy the Cat is our unofficial museum mascot,” Hamshar explains. “He came from the old Catoosa post office, which was built in 1885. Mr. Correll bought it at an auction in 1969 for $400.”

After Correll moved that building to his property, notes Hamshar, it became “a small private museum with rocks and minerals,” a repository for some of the items Correll had amassed throughout his life.

“It had been boarded up for many years when he bought it, and when they opened it up, inside was this naturally mummified cat. I guess he thought, ‘Well, that’s kinda cool.’ So he kept the cat, put him in a little box, and he went into the museum.”

The old post office building was destroyed by a tornado in 1993, but, Hamshar says, “Fluffy survived, and he’s still with us.”

eNot long ago, the Catoosa Historical Society built a replica of the former post office, which stands not far from the present-day Correll Museum and contains a lot of local-history material.

“When they did that,” says Hamshar with a chuckle, “I asked if they’d like to have Fluffy back for their building. For whatever reason, they did not want Fluffy. So we kept him here.”

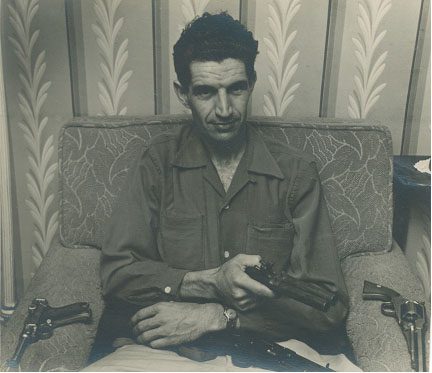

From his display-box home, Fluffy stands sightless watch over an impressive collection of cars and carriages, including a 1917 Packard and 1922 Franklin used in Killers of the Flower Moon. They share space with the likes of a 19th century fringed surrey, an 1898 steam-powered Locomobile, a 1902 Oldsmobile, a 1906 Cadillac runabout, and several others. As impressive as those are, they only represent a fraction of the interests that enlivened the life of longtime Catoosa resident Correll – who, in the 1950s, moved to Oklahoma into a house that sits on the grounds of the present-day museum. (One of his sons currently occupies the residence.)

“It’s an interesting story,” says Hamshar. “D.W. was originally from Rocky Ford, Colorado. His father was a blacksmith during the Depression, so they had hard times. But during World War II, D.W. moved to California and got a job working for McDonnell Douglas, building aircraft. They had two big plants – one in Bakersfield, California, the other in Tulsa.

“While he was in Bakersfield, D.W. met his first wife, who was an Okie. There was a fellow living in that house [on the museum grounds] who worked for McDonnell Douglas in Tulsa. Somehow, these guys came in contact with each other, switched jobs, and switched houses – traded lives, I guess you’d say.”

He chuckles again.

“So that’s how he got to Oklahoma. He worked for McDonnell Douglas for many years, but he did a lot of other things. He owned a service station in Cushing. He had some gas wells. He had a gold mine in Oklahoma, but it was not a profitable endeavor. He did land development, demolition, construction, raised exotic birds, sold rocks, and later in his life, became a jeweler.”

And along the way, he collected. As the museum’s displays reflect, Delmar Webster Correll was a man whose varied enthusiasms led him in all kinds of different directions. Whatever direction he took, he always returned with a lot of keepsakes.

“It’s not unusual, when a good-sized group comes in, for some to get stuck looking at rocks, some ending up with cars they haven’t seen in ages, some to go other places. There’s something for everybody here,” says Hamshar, as he shows me still another exhibit, a display of 100-year-old mining artifacts, minerals and photos.

Photos courtesy the City of Catoosa

“The Tri-State Mining District went from Picher, Oklahoma, to Joplin, Missouri, to Galena, Kansas, [with] lead- and zinc-producing mines for ecabout half a century,” he says. “The ammunition we were firing in both the world wars came out of those mines.”

Nearby stands a mini-library of newspaper tearsheets, featuring local-interest articles from days gone by, and across from those, a seriously impressive array of novelty whiskey decanters that takes up several shelves – two more areas, apparently, of interest to Mr. Correll. And, while the exhibits and displays have been in some instances supplemented by material from others – including Silver Wolf Trading Post owner Harvey Shell and Hamshar himself – the bulk of it was acquired by the city of Catoosa upon Correll’s passing in August of 1998.

“He donated the museum, but did not leave money to run it,” explains Hamshar. “The city had to do that. They made that agreement before he passed away. So the city owns and operates it; my assistant, Jane King, and I are city employees.”

Also at the museum the day I visited was Alex Reiman, who’s with an outreach effort called the Geoscience Program, which the museum picked up, Reiman says, after COVID forced the Tulsa Geoscience Center, its original administrator, to shut its doors.

“It’s a program for kids, and we offer these services for any school that wants to learn more about earth science,” says Reiman. Activities include fossil digs, lessons on how to identify rocks and minerals, and a chance for students to create their own ‘fossil.’

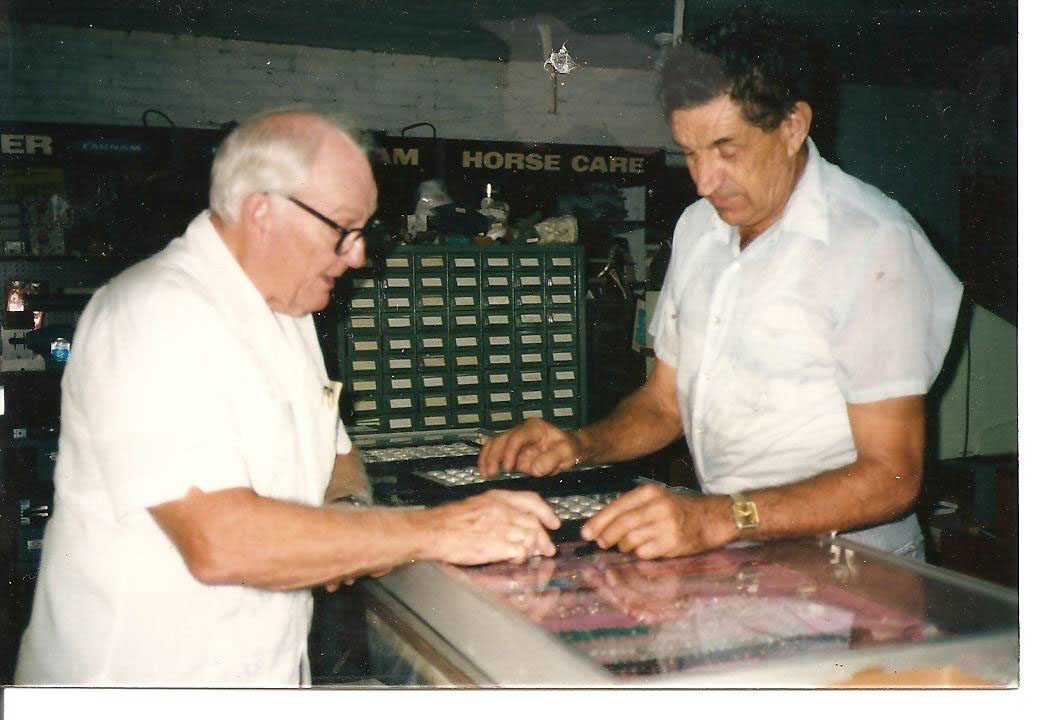

The rock and mineral emphasis continues with the museum’s Bob Hicks Memorial Lapidary Shop, named after a longtime museum employee who helped set up the extensive rock-cutting and polishing equipment and train the employees in how to use it. He died from COVID during the pandemic.

The shop’s finished product, says Hamshar, is either work done on commission or sold in the museum’s gift shop, where the cut and polished stones (including slices of dyed agate rock for a dollar) and many other items (like fossilized trilobites for five dollars each) can be purchased for comparatively little money. The low prices extend to admission charges – $3 for adults, $2 for seniors – with youth under 18, active military personnel, and those holding a Catoosa Library card getting in for free.

“We don’t want anybody to come here and say, ‘Oh, I don’t have the money to do this,’” Hamshar explains. “And we’re trying to keep the prices where everybody can get something [at the gift shop] – especially kids. We want them to go home with a rock or two. Sometimes, that’ll start their own collection.”

The D.W. Correll Museum, 19934 E. Pine St. in Catoosa, is open Tuesday through Saturday. Hours are 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tuesday and Thursday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Wednesday, Friday and Saturday.

(Note: In the print edition of my October column, I miswrote the last name of the Cain’s Ballroom’s David Standingwater. I regret the error, and I thank David for forgiving me.)