Brenda Alford’s grandparents did not speak to her directly about the horrors of the Tulsa Race Massacre. But after she grew up, she realized she had often overheard conversations about the devastation that began on May 31, 1921, in the Greenwood District and its prosperous Black Wall Street. She learned that her grandparents, James and Vasinora Nails Sr., along with her great-uncle Henry Nails, lost their homes and businesses during the 18 hours of mob violence that destroyed more than 1,200 structures and left as many as 300 people dead.

“After I learned about this aspect of our family history, it was pretty devastating to me to know that people I loved and who gave me their best had been treated in this manner,” says Alford, a career services coordinator for Tulsa Technology Center.

For decades, this event went largely ignored in public discourse and historical education. In recent years, however, awareness has strengthened. To commemorate the massacre’s 100th anniversary, Oklahoma leadership established the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, which launched a yearlong observance on May 31, the 99th anniversary. Grant-funded events such as a theatrical performance, concerts and art exhibits are planned monthly as a countdown to the centennial; these will begin when it’s deemed safe in light of COVID-19, says Phil Armstrong, the commission’s project manager.

Also dependent on pandemic precautions is the groundbreaking ceremony for Greenwood Rising, an 11,000-square-foot history center at downtown Tulsa’s Greenwood and Archer. Construction is additionally set to start this summer on Pathway to Hope, a walking path between Greenwood and Elgin avenues – meant to symbolically rejoin the district that was divided by Interstate-244.

“It’s a very unique time for Tulsa, to be able to tell the city, the state, the world, that this happened, that it was devastating, but we can learn together and grow from it,” says Armstrong.

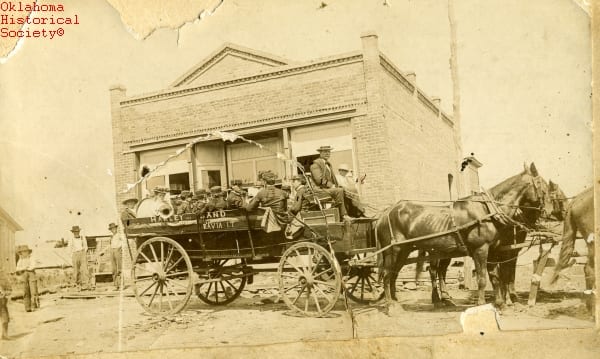

Photos courtesy the Oklahoma Historical Society

Next year, major events are planned from May 31 to June 6.

“Obviously, we’ve made great strides in education and economic advancement for people of color, but there is great work yet to be done,” says Armstrong. “One of the greatest challenges is to combat various stereotypes and negative perceptions of people who live in historic north Tulsa, to bridge the gap between perception and reality, and for people to understand what happens when you wipe out the growth of a bustling and prosperous area and the damage is not addressed for decades.”

State Sen. Kevin Matthews, chairman of the commission, says his vision is “to turn a tragedy into triumph by honoring the lives lost and having a meaningful dialogue about what happened to cause the incident, which we believe was jealousy and envy. Racial tension and hatred are things that are still happening today.”

The commission offers 5 committees: arts and culture; economic development; education; reconciliation; and tourism. Attorney and author Hannibal Johnson is chairman of the education committee, which includes oversight of the Greenwood Rising exhibits.

“Primarily, it’s a narrative history center, which means it’s not focused so much on artifacts as it is on telling the entire story of the Greenwood District,” says Johnson.

The galleries will cover the national context in which the violence happened and describe the massacre and the post-massacre period.

“The third gallery is the road to reconciliation, which focuses on what we have done to move the community closer to a unified whole,” says Johnson. Topics will include police relationships with the black community, criminal justice and reparations, which Johnson says “are all conversations around race that we need to have if we are going to move toward reconciliation, but that require a certain amount of courage to engage in.”

U.S. Sen. James Lankford, a commission member, says that while much positive change has been made in the last 100 years, “there’s still more to go. We worked very hard on getting the curriculum into schools. It’s extremely important that the next generation of students learn about this. And it’s important that we have a physical location that people can visit, a place of remembrance and reflection.”

Another large point of conversation is the likelihood of mass graves in Tulsa, as martial law was declared after the violence subsided during the massacre, and survivors were not allowed to bury their loved ones.

Alford is the chairman of the 1921 Mass Graves Investigation Public Oversight Committee, which is working with anthropologists and archaeologists who have identified two likely common graves. Further investigation had been scheduled to begin in April but was postponed indefinitely by the pandemic, she says.

Alford’s ancestors left a legacy of courage and industry. Besides their flagship business, Nails Brothers Shoe Shop and Record Shop, they owned a dance pavilion, a roller rink, a taxi service and a chauffeur business. Her aunt, Cecelia Nails Palmer, who was 2 when the massacre happened, became a university professor and Fulbright scholar.

“They were courageous people,” Alford says. “They taught their kids to be very positive-minded people. They had every reason in the world not to want to do that.”

While racism still exists heavily across the world, the centennial commission is taking steps in the right direction with its unifying infrastructure, events and more expansive education on a disturbing part of Oklahoma history.

“Secrets have power,” says Matthews, “but we take the power away by unveiling it and discussing it.”