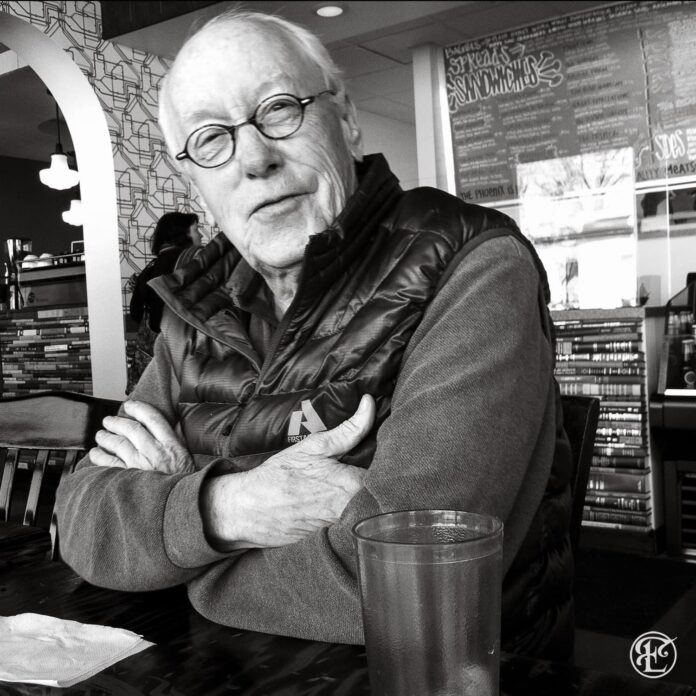

His name was Jim Millaway, but to a generation of Oklahomans, he was Sherman Oaks, or Mr. Mystery, or even sportscaster Stan Sharpe (“It’s not whether you win or lose, it’s whether you beat the point spread”), a character he created during his time as a morning-drive personality on radio station KMOD. His media visibility began in 1970 and ran for somewhere around a decade and a half, establishing him as a comedic cult figure known for his off-trail humor and unique angle of vision. Millaway, who died on December 23 of last year, will be remembered with fondness by a ton of Tulsa-area baby boomers for a good long time.

Almost from the beginning of his Tulsa media run, I knew him. And for about two decades, from the ’80s into the dawning of the 21st century, we were best friends.

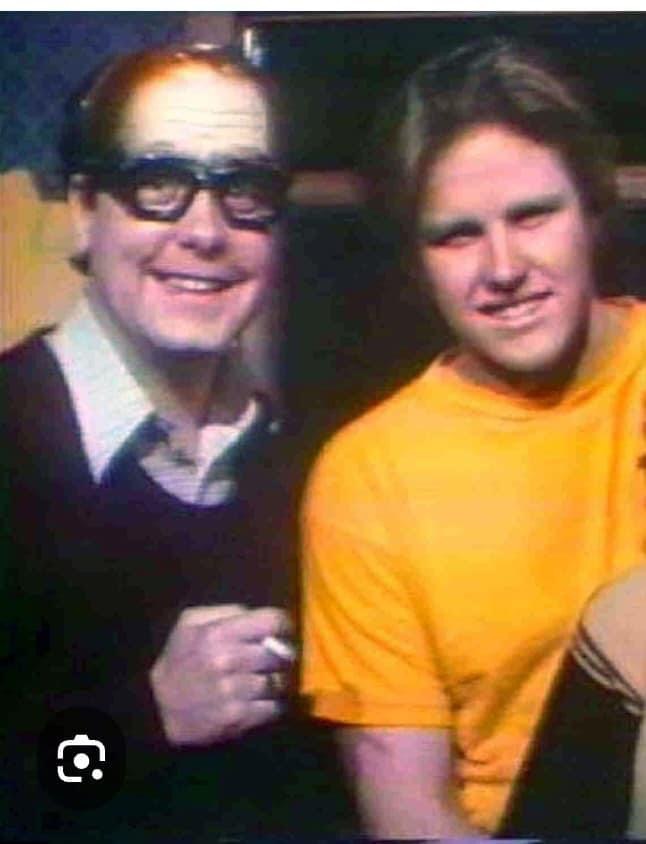

I first met Jim in the summer of 1970, only a couple of months after a late-night show called The Uncanny Film Festival & Camp Meeting had debuted on KOTV, Channel 6, in Tulsa. Hosted by Dr. Mazeppa Pompazoidi, created by Jim’s friend Gailard Sartain, and featuring Millaway’s characters Mr. Mystery and Sherman Oaks in support, the Mazeppa show – as it would soon become popularly known – came squarely out of the tradition established in the late 1950s with a national effort called Shock Theater. It was an invention of the Screen Gems company, which had released a package of old theatrical monster movies to TV and suggested that local television stations use their own talent to introduce the films. Soon, dozens of horror hosts doing ghoulish and ostensibly funny sketches around segments of the films had popped up all over the country (including on KOTV itself, where the characters Igor and Hornstaff did the honors).

Sartain, Millaway and their cohorts took that basic Shock Theater premise and put a youthful, subversively irreverent, and wildly humorous spin on it. It wasn’t long before word got out and kids all over northeastern Oklahoma were tuning in. It was comedy that belonged to them, not their folks, and they dug it.

Coincidentally, the Mazeppa show’s three-year run dovetailed with a magical time in Tulsa – the legendary, if brief, period that saw Leon Russell, who’d become a wildly successful international superstar, return to his hometown, blanketing the city with rock ‘n’ roll stardust. He became a fan of the Mazeppa show, leading to one of its most memorable episodes, the 1970 Christmas special.

In that one, Millaway, as the ski-masked Mr. Mystery, spends much of the show bragging about how he knows “Paul McCartley” and other famous rockers whose names he consistently butchers. At the end, he pulls off his mask, and it’s Leon Russell himself, who then sits down at the piano and does a song. My group out of Oklahoma State University, the Beef Squad, guested on that same episode; we had been the first band to play the Mazeppa show, and I believe that was our last appearance, as I went on active military duty the next year.

By the time the holiday number aired, Gailard, Jim and I had become good friends. I remember coming home on leave in 1972, fresh out of Vietnam. Jim took me to Boston Avenue Market, a live-music club at 18th and Boston. There, I saw firsthand how Leon Russell’s return had altered Tulsa’s reality. The entire clientele seemed to be made up of unemployed backup singers and young members of the British nobility.

At one point in the evening, looking around the noisy, uber-hip scene, Millaway told me, “You know, if you could somehow get Rolling Stone a week early, you’d own everyone in this place.”

By the time I finished my active duty, in December of ’73, the Mazeppa show was no more. Sartain had gone on to join the cast of the nationally syndicated country-music variety show Hee Haw and was beginning to find the sorts of film roles that would establish him as an enduring Hollywood character actor. Another Mazeppa show cast member, Gary Busey, was also starting to see the first stirrings of his own long-term cinema success.

Millaway, however, took his opportunities around his hometown, except for a brief foray to the West Coast in the late ’70s, where he became a staff writer for the Shields and Yarnell television show, “writing comedy for mimes,” as he sardonically described it to me at the time. (Sartain was a cast member on the program.) I also remember doing a radio appearance with Gailard and Jim after my military service; I believe that series was called The Unfilmy Can Festival. The two of them spent most of our interview time remarking about how my face had cleared up since I’d gone overseas.

In the subsequent years, Millaway wrote material for country stars Roy Clark and Hank Thompson, had the aforementioned morning-show run at the top-rated KMOD, and spun that gig off into a job as the host of Creature Feature (later Groovy Movie), another sketch-comedy series wrapped around old theatrical features. Airing on KOKI, Channel 23, and co-starring Steve Pickle, it featured an exceptionally talented young woman going by the name of Jeannie Summers, who’d been working with Millaway at KMOD. Under her real name, Jeanne Tripplehorn, she would go on – like Sartain and Busey before her – to a notable and lasting career in the movies.

In the mid-’80s, Millaway hosted an hour-long special, The Sherman Oaks Comedy Network, which guest-starred Sartain, who appeared in a Spam-carving segment. The one-shot program also utilized a couple of 16mm films from my collection – an episode of the ‘60s ABC-TV series Expedition called “The Vanishing Musk Ox,” and an instructional short called “How to Twirl a Baton.”

Collecting and watching old 16mm films, especially in the days before home video became fully established, was one of the things Jim and our families enjoyed sharing. We also got into baseball – cards, games, and a fantasy league with some other friends – along with comic books and, especially, pulp magazines, those garish all-fiction publications that thrived in the ‘30s and ‘40s. Together, Jim and I traveled to a number of pulp-magazine conventions, where we never failed to have a fine old time.

Jim – who for some reason called me “Jabbo” – was one of those guys who would blurt out stuff for comedic effect wherever he was, especially if he knew it would make you a little uncomfortable. I remember, for instance, being in a crowded elevator with him when he started asking me, in a loud voice, if I’d gotten any new items for my “hats of the world collection.”

“I just got one in from Chad that I’m real proud of,” he said, and continued to chatter about headgear until we mercifully reached our floor.

Although he rarely imbibed more than one or two beers at a sitting, for many years Jim was a member of the Drinklings, a loose group of writers and musicians who gathered regularly after work to hoist a few. Sipping at his beer, he would dispense acerbic, off-kilter wisdom, something he really seemed to enjoy. I remember, also, that he was a very open-fisted guy, the kind who was quick to pick up a tab.

When I think about him, though, I keep going back to an incident that happened on a flight we were taking to a pulp-mag convention in Ohio. Later on, we found out that there had been a pinhole leak in the cabin; however, at the time the plane went into a virtual nosedive, losing hundreds of feet of altitude in seconds, we had no clue about what was happening. The oxygen masks wriggled down and an obviously flustered stewardess came through, exhorting us all to put them on immediately.

Jim and I did. And as the plane continued streaking downward, with kids screaming and people shouting all around us, he looked at me and said, “I like the flight better where they serve lunch.”