Most think of Helen Keller – who had nearly total vision and hearing loss – when they picture a deafblind person, says Jody Harlan, the communications director for the Oklahoma Department of Rehabilitation Services (ODRS). But deafblind people, defined as those with combined hearing and vision loss limiting access to both auditory and visual information, are more prevalent in society than one may think.

“People can have a range of vision and hearing losses and can develop both losses as they age, or due to illness,” says Harlan. “Some don’t know that people they know are deafblind. But there are services and non-profits operated by people like Jeri Lynn-Cooper and Cassandra Oates that are making the public aware of deafblindness and the needs of deafblind people.”

It’s all a matter of perspective, says Oates, the founder and CEO of the Sight-Hearing Encouragement Program, who is deafblind herself.

“Because we are normal,” says Oates. “It’s like if someone lost their foot and a hand. They are still a normal person, but would possibly need a prosthetic to help them utilize that lost or missing body part. Being deafblind is the same thing. We don’t ‘suffer’ from the sensory loss, but we experience the loss and learn to live a different way of getting around and communicating.”

Oates’ program helps connect deafblind people to the world and the environment around them, she says.

“We have workshops, educational classes, trips, camps and more to get everyone out and moving – and not shut-in from the world. We are working to rapidly expand and touch more and more cities to show the world we the deafblind individuals are strong and are independent. We can do it.”

Lynn-Cooper, founder and CEO of Jeri’s House who is also deafblind, shares the same “can-do” attitude.

At Jeri’s House, individuals participate in a variety of activities. They learn communication through Braille and/or sign language; hone independent living skills such cleaning, cooking, organizing, labeling, and identifying currency and clothing; get help with medical management; enjoy leisure activities, advocacy and Bible study; and generally get assistance in adjusting to their ‘new normal’. Awareness is key, says Lynn-Cooper.

“I wish others wouldn’t be afraid or intimidated by those of us who are deafblind,” she says. “I understand their awkwardness, because they don’t know what to do or how to act. Simply say, ‘How can I talk with you?’ Often we are isolated due to lack of education or awareness.”

There are also schools for the blind and deaf in Oklahoma, says Harlan. ODRS operates the Oklahoma School for the Blind in Muskogee and the Oklahoma School for the Deaf in Sulphur. Both schools provide services free of charge to students who attend class on campus, commuter students and those who attend summer school.

“In addition, the schools provide free outreach services, including vision or hearing evaluations, curriculum assistance and consultation benefiting students who attend other public schools, their parents and educators,” says Harlan.

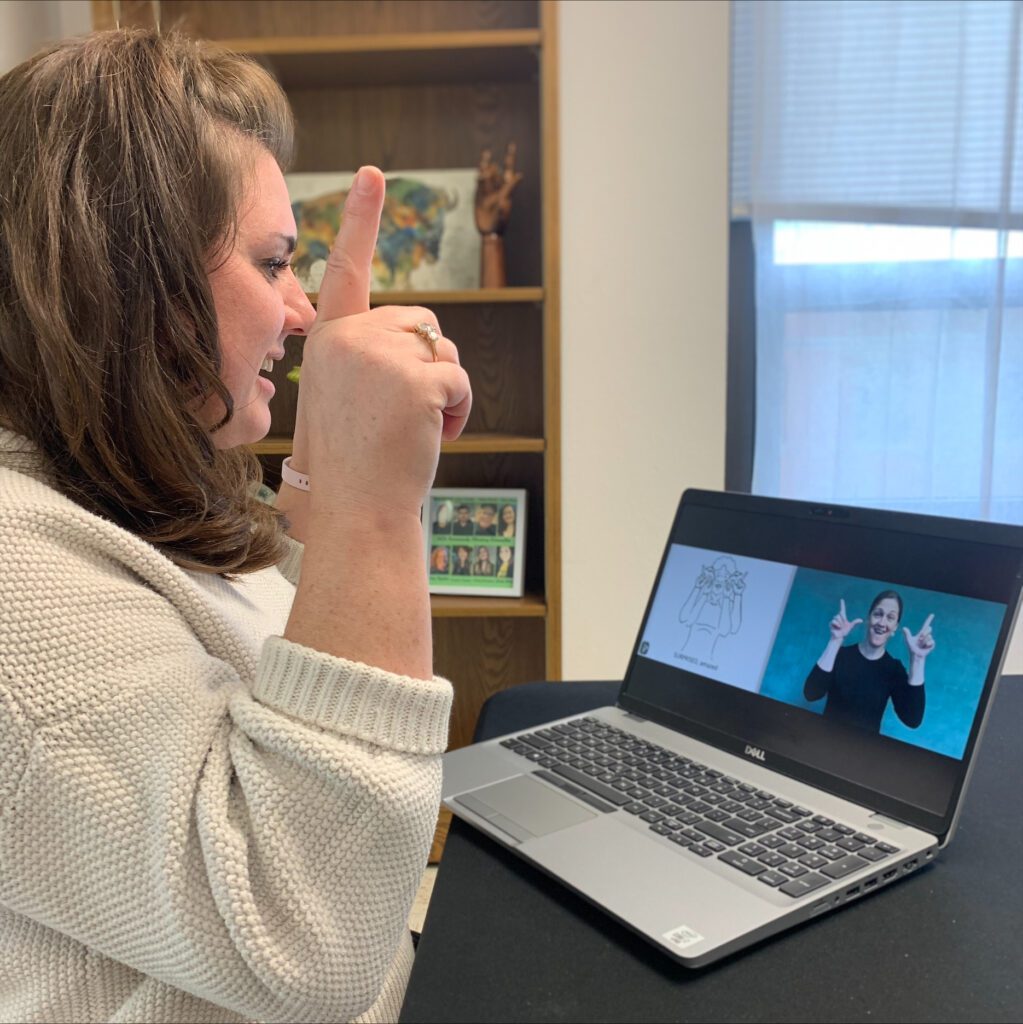

Last year, 452,934 students took free online American Sign Language 1 and 2 classes through the Oklahoma School for the Deaf, says Harlan. Classes are offered in spring and fall. Check out osb.k12.ok.us and osd.k12.ok.us to enroll or learn more.

Communication Tips

When conferring with a person who has dual sensory loss, the ODRS offers the following tips:

• Say the person’s name or lightly touch them on the hand or arm before speaking to them.

• Speak at a normal volume. You may need to move closer but don’t raise your voice.

• Speak at a normal rate, unless you have a tendency to speak fast.

• Do not over emphasize or exaggerate your speech.

• In an area that echoes, you may need to speak a little softer and move a little closer to the individual.

• When in a group setting, attempt to have only one person speaking at a time.

• Specify when changing topics.

• Do not answer questions that are directed to the individual.

• Inform the person when you are moving away or leaving.

• When using phonetics, use words that are not similar to others. For example, “T” for tango and “P” for puppy.

• When stating numbers, use single digits. For example, “five six” rather than “fifty six.”

• Give directions such as “left” or “right” rather than “over here” or tapping on a table. Distinguishing where sounds are coming from is difficult.

• When something needs to be repeated, only one person needs to restate it.

• You cannot go wrong with simply asking the individual, when in doubt, “How can we best communicate?”