Those of us who’ve spilled a lot of ink and devoted blocks of airtime to what many call the classic Tulsa Sound know that there were, and are, other Tulsa Sounds out there – all featuring their own stars, their own excitement, their own validity and vitality.

And while there were a few Oklahoma writers – my good friend Thomas Conner among them – who devoted considerable amounts of time and talent to chronicling Tulsa’s punk-music scene, punk has long been one of the most overlooked of the city’s sounds.

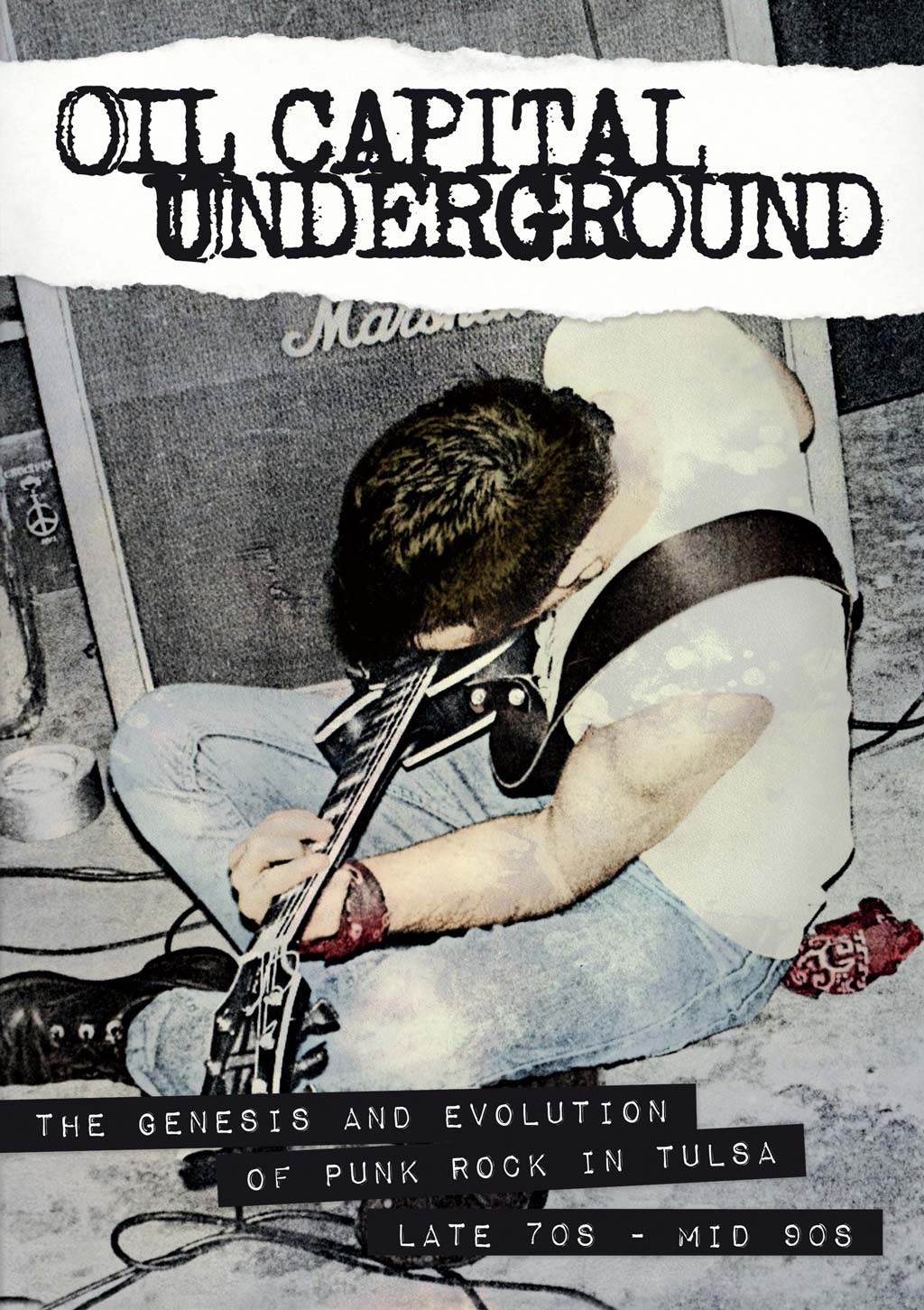

That situation, however, just changed. Oil Capital Underground, a swift, two-hour documentary from writer-director Bryan Crain and his co-producer, Dave Cantrell, gives viewers a sweeping look at – as the doc’s somewhat unwieldy but accurate subtitle puts it – The Genesis and Evolution of Punk Rock in Tulsa, Late ’70s-Mid ’90s. It’s a riveting piece of work, made so in part by the use of original concert and television footage and an inventive graphic style that fits the subject matter perfectly. Crain worked with Terry Waska on the latter; like Crain and Cantrell, Waska is a veteran of the scene after playing bass with the metal-punk bands Pitbulls on Crack and Asylum.

“I was in a band called the Outcasts, which was my main band,” Crain says. “We did parties and stuff, and we played with a lot of the other ones, but nobody talked about us. We weren’t that big. This doc is more about the bigger bands that either toured or put out cassettes or CDs.”

Crain’s collaborators on Oil Capital Underground fall into that category. Cantrell was lead singer for Bunnies of Doom, among other groups, while Waska’s Pitbulls on Crack was another major Tulsa punk act.

But the biggest of them all, notes Crain, was N.O.T.A. (standing for None of the Above), which transcended local success.

“N.O.T.A. toured with the Dead Kennedys and a lot of other national bands,” he says. “They put out records. They played out of state more than they played here. And they put Tulsa on the map. If they would’ve stayed together, they would’ve been as big as Black Flag or anyone else. And they’re still recognized. People today still love N.O.T.A.”

As is the case with most of the other bands covered in the documentary, N.O.T.A. is represented not only by archival material but also by new interviews. In one of them, vocalist-guitarist Jeff Klein reminds viewers that punk was as much as anything a reaction to the arena acts that had come to dominate rock music in the late ’70s.

“Anything that wasn’t Journey, or Styx, or Emerson Lake and Palmer,” he says, “was punk rock.”

And while there were significant differences between the American and British punk movements, including the reasons for their respective existences, many would agree with interviewee Anthony Lookout (of the New Mysterians) that the appearance of the Sex Pistols – the most notorious of Britain’s punk acts – at the Cain’s Ballroom in January 1978 fired the starting gun for Tulsa’s punk movement.

Once it began, Klein says, a lot of different musical styles gathered under the same umbrella, without much separation between punk music and what was being called new wave. Because they were all outside the mainstream, they sought more or less common ground. The documentary credits Joe Danger (New Mysterians, Los Reactors) with finding a Tulsa venue that would commit to featuring these alternative rock-music styles.

“The first place was the Bleu Grotto,” Crain says. “It was only open for maybe six months, but Joe Danger went in there and talked the owner into letting them have shows. So that was the starting point, and it was a really small period of time. Then after that, in the early ’80s, was the Crystal Pistol, over on North Sheridan.”

After the national punk act Black Flag played the Crystal Pistol, he adds, “that’s really when the scene started to separate. It separated the real punks from new wave. In the Bleu Grotto days, they were kind of together. A band called the Jacks had played with N.O.T.A., and the Jacks were real mellow. Back then, it was like, ‘Hey, you’re a different band. I’m a different band. Let’s play.’”

The Bleu Grotto and Crystal Pistol are long gone, along with most of the other punk venues of the ’80s and ’90s. But, as is the case with the people who made the music, some of the operators and promoters are still very much around, including a couple of well-known names: Davit Souders of Ikon and Khaled Rahhal of Club Nitro. Both are featured in Oil Capital Underground.

“Souders had a dance club, but he would have punk bands like D.R.I. in there,” Crain says. “It was so bizarre. He’d have local bands play with national acts, and that was genius. I went there all the time.

“K. Rahhal is like the godfather of the whole [Tulsa] punk scene. He started in ’84, and he went the longest. We love him now, but we hated him then because he was so mean. But he was trying to wrangle all these teenagers, and they’re slam dancing.

“He’d let you play, even if you sucked. It could be your first gig, you could be terrible or great, but he would bring you back. That’s one good thing about K. His longevity and what he provided was what makes him important. I mean, where are you going to play if you don’t play at Nitro and you’re terrible? It was a starting-off point.”

Rahhal is one of the most colorful figures in the Oil Capital Underground tapestry, but he’s far from the only one. There’s a conversational quality to Crain’s interviewing that allows the personality of each subject to shine through.

“I wanted this to look more immediate,” says Crain, trying to emulate Dogtown & Z-Boys, the award-winning skateboarding documentary from 2001. “For the most part, I wanted it to be like talking to friends. I didn’t want it to be too pretty. I mean, I’m a photographer, I’ve got to have framing and stuff, but I wanted it to be like I walked up and started talking to them. That was the whole feeling.”

Early in Oil Capital Underground, Anthony Lookout concedes that “maybe we looked threatening” from the outside, and, indeed, much of the film conveys that same sense of danger. Decades may have gone by, but much of this music still appears angry and extreme.

Was it? To really know, you probably had to be there.

“The music wasn’t dangerous,” Crain says. “Sometimes there were skinheads hanging around with the punks, and they’d always provoke fights. But other than that, except for the slam dancing, it wasn’t dangerous. It was just aggressive and young and full of angst. You didn’t have to be the greatest player to play it, but there were some phenomenal players who did, like [drummer] Brandon Holder. I mean, he played with Leon Russell. He was in a band called Baby M, and they were actually great musicians.”

Ultimately, he adds, those great musicians are who he wants to celebrate in Oil Capital Underground.

“Except for maybe YouTube or word of mouth, these incredible players have gone unnoticed for all these years,” he says. “Hopefully, they get some recognition now.”

Already, the documentary itself has won major recognition. In late June, it was one of 10 features from around the globe to earn a Gold Lion Award at the Barcelona International Film Festival.

Oil Capital Underground begins a run at Tulsa’s Circle Cinema at 7:30 p.m. Aug. 3.