Once again, we’re deep into another season of baseball, and for those of us who love the sport like no other, much of its charm lies in its timelessness.

It’s not just that baseball is one of the few sports with no clock, meaning that any game could theoretically go on forever (just as they sometimes seemed to do during our golden summers of pickup ball). It’s also that, in a sense, the game has gone on forever, with names and faces flowing through it like an unending river.

As Donald Hall writes in his 1976 book, Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball: “Seasons and teams shift, blur into each other, change radically or appear to change, and restore themselves to old ways again…. In the country of baseball, time is the air we breathe, and the wind swirls us backward and forward, until we seem so reckoned in time and seasons that all time and all seasons become the same.”

In no other sport is the past so inextricably linked to the present, and the present to the future, in that timeless continuum. So it’s only right that this column about a ballplayer from my hometown of Chelsea goes back a couple of generations, and that he was a fan of the baseballers of an earlier generation.

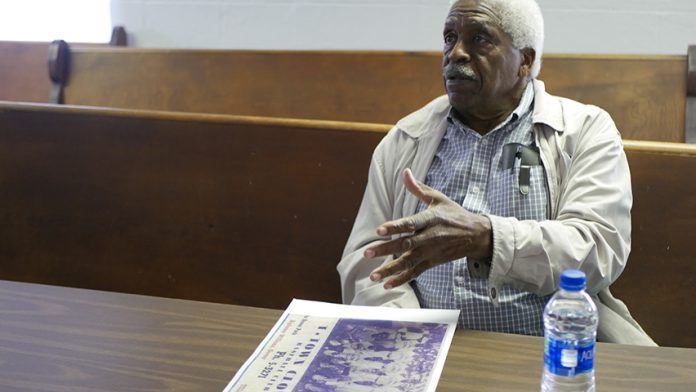

“We had a radio, and my dad kept it on the St. Louis Cardinals,” Gerome Riley says with a chuckle. “On Saturday nights, it was the Grand Ole Opry, and through the week, it was the St. Louis Cardinals. I used to be able to name you all the players the St. Louis Cardinals had – Red Munger, Stan Musial, Red Shoendienst, Harry Brecheen – all of those old guys from way back when. And I could name all the players on most all the teams they played.”

Gerome’s friend Ralph Terry lived a couple of blocks away, and the two boys spent days together hunting, fishing, and, when the season arrived, playing lots of baseball.

“We used to go to [Chelsea’s] McSpadden Park every day in the summer, when school was out, and we’d be up there from sunup to sundown,” Gerome says.

Ralph was the pitcher in a lot of those contests, and Gerome was often the catcher. (Much later, Ralph called Gerome one of the best catchers he ever had.)

However, that pairing only went for what Gerome terms “recreational” games – when a bunch of kids showed up and divided themselves into teams. It was a relationship that could not extend into organized sports. In those Jim Crow days, Gerome and his siblings attended a different school, named after African-American poet and author Paul Laurence Dunbar, so they couldn’t play for Chelsea’s public school teams.

Gerome remembers that legendary Chelsea coach Rupert Cross let him and his brothers practice with the high school squad; in the summers, when Cross coached Chelsea’s American Legion team, he sometimes put them in as late-inning replacements.

Meanwhile, the 1947 professional baseball season got underway and Gerome switched his allegiance from the Cardinals to the Brooklyn Dodgers – along with millions of other African-American fans, who finally saw a member of their own race crack the major leagues’ color barrier.

“All blacks were Brooklyn Dodger fans because of Jackie Robinson,” Gerome says. “But Ralph was a Yankee fan. And we used to talk about it. He said to me, ‘Riley, I’m gonna play with the Yankees one of these days.’ And I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding.’”

He wasn’t. At age 17, Ralph signed with the Yankees. Breaking into the majors in 1956, he went on to become a two-time All-Star, a World Series MVP and the top right-handed pitcher on what some say was the greatest baseball team of all time – the 1961 Yankees. He remains the only pitcher to throw the final pitch in two World Series Game 7s.

“We just didn’t get the exposure. We had outstanding ballplayers, but they never got the chance.”

Well before all that happened to his friend, Gerome began attending high school in nearby Claremore since Dunbar ended at the eighth grade. And it was there that he encountered the Claremore Clowns, a semi-pro black baseball team playing throughout the area. Just about every place of any size had what was called a town team made up of locals, and the Clowns played them, Gerome recalls, “on a 60-40 basis.”

“The home team got 60 percent of the gate receipts, and the visitors got 40,” he says. “We made money to buy gas, and money to buy some beer or food or something, but that’s all. There weren’t any individual salaries or anything like that.

“We would probably play two or three times a week – night games – and then on Sunday, when we always had a game. A lot of those cities and towns, they were against blacks. But they always loved to play us because they loved to see the black guys play. That’s why we drew such a crowd. Of course, they always wanted to beat us, too.”

Gerome was in high school when he started with the Clowns – or, rather, with an auxiliary team.

“Ange Lee Alexander, who played on the Clowns, got a lot of us young high school guys and made a team out of us,” he says. “We were called the Hot Shots, and we’d play before the Clowns against junior teams from those towns. Mr. Alexander had hogs. He’d haul ’em in an old pickup, and when we got ready to go play ball, he’d wash that truck out and that’s what we rode in, in the back.”

He laughs.

“I never will forget that.”

As the original team members aged out, the Hot Shots, including Gerome, moved onto the Clowns’ roster, and the barnstorming continued.

As indicated by their name, there was a comical aspect to the Claremore Clowns, something that was often part and parcel of black touring outfits in those days.

“They had what they called a ‘shadow ball,’ where a guy would swing and pretend he’d gotten a hit, and they’d act like they were throwing it around, hit their hands in their glove like they were catching the ball, and when he got to home plate the catcher would pull a ball out of his pocket and tag him out,” Gerome says. “Mac Kilpatrick was our catcher, and he always caught with a cigar in his mouth.”

But once the pre-game hijinks ended, he adds, the team got “real serious” about playing.

“I could name you some of those guys I know could’ve gone on and played professional ball,” he says. “We just didn’t get the exposure. We had outstanding ballplayers, but they never got the chance.”

As an example, Gerome cites teammate Charles Ray, whose son ended up notching a 10-year career as a major league infielder.

“Charles Ray didn’t get to play [pro ball], but his son Johnny got on high school and college teams and got the exposure,” Gerome says. “He got that recognition. That’s why it didn’t happen for us. We came up playing just because we loved the game.”

For Gerome, the Claremore Clowns were always a sideline – or, perhaps, a manifestation of that lasting love. The Clowns faded away, along with the town teams and other barnstormers, in the late 1950s, even as integration reached his native Oklahoma.

So, as Ralph Terry made his ascent to the major leagues, his friend and former battery mate pursued a successful career with Phillips Petroleum by fighting his way up to become a station manager in an era when that didn’t happen much with people of his race.

Some 60 years later, Gerome has become well-known as a sports historian as well as an educator and advocate for voters’ rights.

A couple of years ago, I was privileged to help Ralph Terry write his autobiography, Right Down the Middle. With this column, I’m happy to have been able to tell a little bit of his old friend’s baseball story as well.