photo by Chris Humphrey Photographer.

Anniversaries don’t always bring pleasant memories. Some dates on the calendar remind us of horrific episodes, leaving us to shake our heads with disbelief. We may want to forget, but that’s about the worst we could do. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 falls firmly into this category: a wretched event that should be remembered so that we can learn and never repeat it.

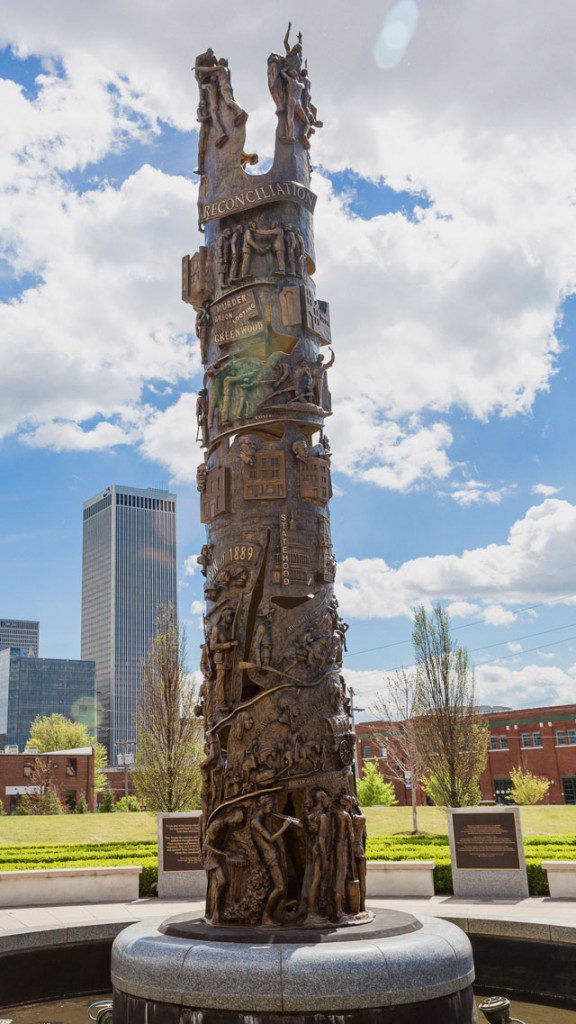

Today, the location of this millstone of hate and conflict offers beacons of hope for the future. The Greenwood District, epicenter of the massacre in 1921, houses the Greenwood Cultural Center and the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation and Reconciliation Park, among other establishments.

Rewind the clock 100 years; the Greenwood District in downtown Tulsa looks entirely different. The community thrived with prominent African-American-owned businesses and homes.

“All manner of businesses, including hotels, movies theaters, churches, pharmacies, haberdasheries, professional offices, shine parlors, beauty salons and much more dotted the Greenwood District landscape. Home ownership and community pride swelled,” says Frances Jordan-Rakestraw, executive director of the Greenwood Cultural Center.

Segregation laws led to the inception of this community, but the inhabitants did not limit their ability and created a thriving district with a bustling thoroughfare of commerce dubbed Black Wall Street.

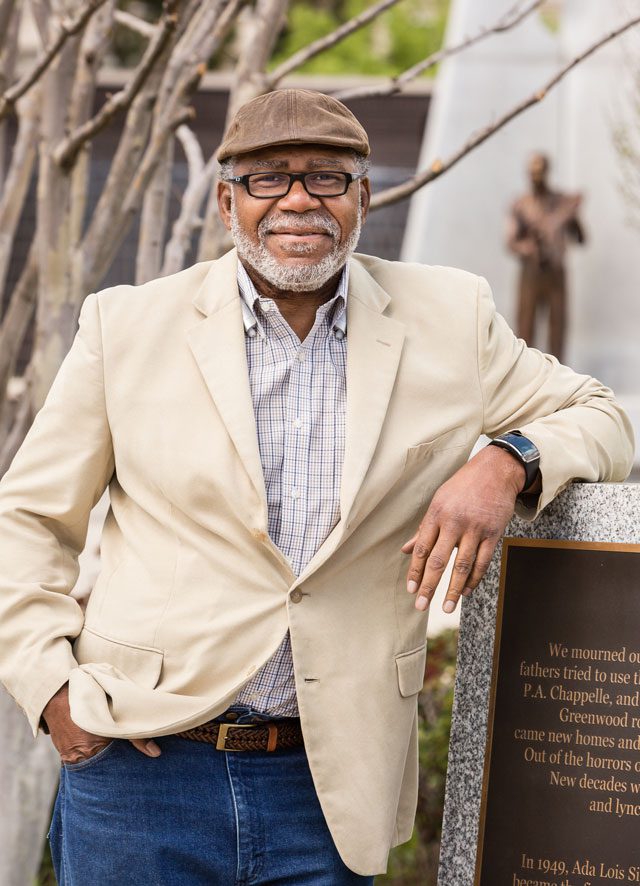

“In the face of restrictive laws and practices of society that forbade such an independent entrepreneurially successful community [to be] possible in the U.S. during Jim Crow and segregation, Greenwood beat the odds,” says Reuben Gant, interim executive director of the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation.

Everything changed precipitously May 31 and into June 1, 1921. That night, an angry white mob destroyed Greenwood by burning it to the ground. The events left thousands of African-Americans homeless and wiped out hundreds of businesses. The violence was not restricted to property. Between 50 and 300 people died; the death toll is not definitive. What is certain is that Greenwood and its inhabitants were devastated. The area was rebuilt after the events by its victims, but the damage done to the lives and culture there was felt for decades.

During the 1970s and ’80s, leaders recognized the need to preserve the history of the Greenwood district. The Greenwood Cultural Center was built.

“GCC works primarily to teach about the history of the Greenwood District and preserve historical artifacts for educational purposes,” Jordan-Rakestraw says.

The Greenwood Cultural Center has told the story of Greenwood for 30 years with pictorial exhibits showcasing the history of the area. It incorporates the preserved Mabel B. Little Heritage House, the only neighborhood home still standing from the riot. The center includes the Black Wall Street monument and photos, newspaper articles and maps illustrating the riot.

“The Greenwood Cultural Center is an historical, economic and cultural focal point of the African-American experience in Tulsa and in Oklahoma,” Jordan-Rakestraw says.

The cultural center also houses the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, which works to preserve the history and spirit of this community. It’s named for John Hope Franklin, a native of the black township of Rentiesville and graduate of Booker T. Washington High School in Tulsa. He received a doctorate in history from Harvard and was the history department chair for many years at the University of Chicago. He wrote many books about the African-American experience. His father, civil rights lawyer Buck Franklin, defended many African-Americans during and after the race riot.

“The center’s vision is to transform society’s division into social harmony,” Gant says. “In doing so, the center has adopted as its mission, ‘In the spirit of John Hope Franklin, the center promotes reconciliation and generates trust through scholarly work and constructive community engagement.’”

This is accomplished through an annual national symposium that takes an in-depth look at reconciliation in its many forms and from a variety of angles, the gathering of archival information about Greenwood both before and after the riot, and dialogue in the community about reconciliation.

Remembering the massacre and the people whose lives were changed forever is important in order to learn lessons that we can apply today. The Franklin center highlights the impact that reconciliation can have on our community and the world. The center has created an “open forum to address the issue of race, to combat stereotypes and misperceptions that permeate throughout society because of unfamiliarity,” Gant says.

This is all done in an atmosphere that encourages people from different walks of life to listen, interact and really hear one another with no expectation of conformity, and to foster greater familiarity and understanding, he says.

Jordan-Rakestraw adds: “The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre must be taught. If we fail to understand our past, we risk making the same mistakes over and over again. Knowledgeable, thoughtful facilitators allow us to explore this history and the underlying racial context it reflects in ways that move us forward together as a community.”