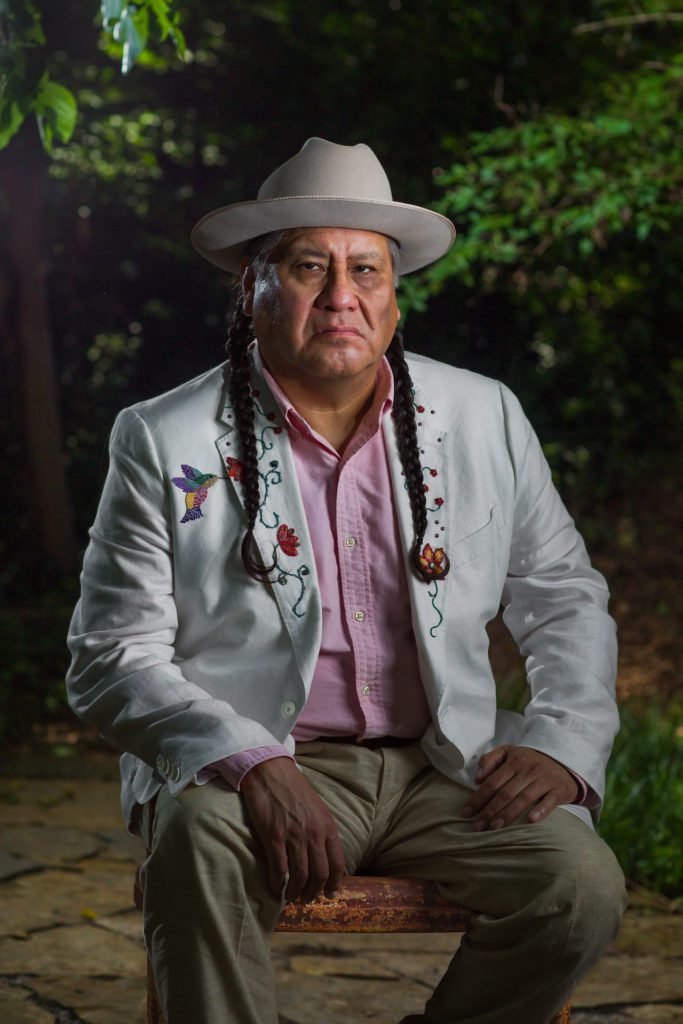

All Eyes on Yancey Red Corn

It was a red carpet appearance like no other.

Yancey Red Corn and Osage Nation Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear, shoulders wrapped in symbolically meaningful tribal blankets, stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Killers of the Flower Moon star Leonardo DeCaprio as they posed for photographs.

Principal actor Lily Gladstone and other Native women invited to the premiere at the May 20 Cannes Film Festival wore spectacular gowns by Native designers, or blankets and shawls handmade by family members.

The photos and video were stunning, and so was what happened inside the theater: a nine-minute standing ovation for the Martin Scorsese film, shot in Oklahoma and based on the nonfiction book by David Grann. The movie also stars Robert DeNiro, Jesse Plemons and Brendan Fraser, telling the story of oil-rich Osage Indians murdered for their headrights during the “Osage Reign of Terror” in the 1920s. The movie is scheduled for an October opening.

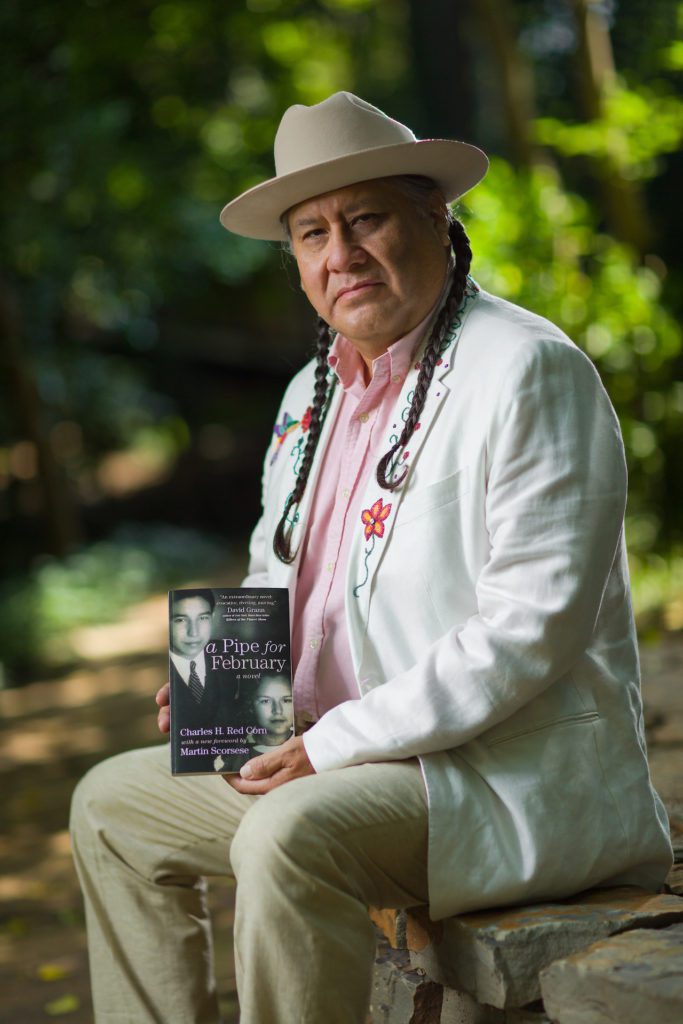

Red Corn, an entrepreneur who lives in Norman, plays the role of Chief Bonnicastle. While the chief is not featured in Grann’s book, he is a character in A Pipe for February, a novel written by Yancey Red Corn’s father, Charles H. Red Corn, who died in 2017. Scorsese relied heavily on the novel as he made changes to the script after meeting people in Osage County.

Red Corn, a tribal name-giver who has been dancing in Osage ceremonies since the age of three, was invited to help oversee historical and cultural accuracy.

“They used me as a consultant, so I felt like I was part of the process,” he says.

Red Corn assists families in choosing Osage names for their children, and the red broadcloth he wore over his tuxedo at Cannes was his name-giver blanket, made by his mother and sister and trimmed in ribbon. His mother is the acclaimed Caddo potter Jeri Redcorn, and his sister, Moira, a Pawhuska physician and artist, was Red Corn’s guest for the trip to France.

Talee Red Corn, Yancey’s cousin with whom he grew up in the Pawhuska Osage Indian Village, sat beside him that day in the limo as they approached the theater. Talee portrays an Osage priest in the movie.

“I told [Talee], let’s just walk on that red carpet like we walk into our dances in Pawhuska: like we belong there,” says Red Corn.

Dozens of tribal citizens worked as staff members and extras as the film was being shot, Red Corn mentions.

“Everywhere I looked, I would see Osage people that I knew,” he says.

The movie was not easy to watch, Red Corn says, “but it’s a great film, and it’s a story that needs to be told.”

Infrastructure Updates

An 11-story hotel with more than 400 rooms. Indoor and outdoor waterparks, a family entertainment center, an art market, retail shops and several dining options. It’s called the Okana Resort, and although it’s not scheduled to open until the spring of 2025, the $400 million project is already changing the landscape at OKC’s First Americans Museum.

“We expect to add about 800 jobs to the Oklahoma City area, and a $97 million economic impact the first year,” says Chickasaw Lt. Gov. Chris Anoatubby.

“It will complement the First Americans Museum as well, because that’s really the centerpiece,” he adds.

The Chickasaw Nation has more than 100 businesses scattered across its tribal boundaries, with construction and expansion projects planned or underway for casino resorts in several cities.

Anoatubby says he’s excited about a partnership with Indian Health Service to build a hospital in the Newcastle area. The tribe has hospitals in such cities as Tahlequah, Claremore, Lawton and Okemah, but none in the OKC metro.

“One of our goals is to try to get healthcare services no more than an hour away from all tribal citizens,” says Anoatubby. “All of our facilities are very highly utilized. We serve members of other tribes as well.”

The Cherokee Nation broke ground in April on a $400 million hospital that will replace the nearly 40-year-old W.W. Hastings Hospital in Tahlequah.

“To start building the walls that will bear our future citizens, save countless Cherokee lives and heal and comfort our sick in their most critical time of need is a defining moment in the Cherokee Nation,” Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said during the ceremony.

The Choctaw Nation partnered with country music legend Reba McEntire to create Reba’s Place, a dining and entertainment venue that opened this year in Atoka.

“The opening of Reba’s Place has created more than 100 jobs, and about 50% of those positions are filled by members of a recognized tribe. We’ve seen more than 230,000 visitors stop by the restaurant, resulting in an annual impact of more than $11 million to the area,” says Tammye Gwin, senior executive officer for the tribe’s Division of Strategic Development.

“Another project we are very excited about is the $238 million Choctaw Landing in Hochatown,” Gwin says. “We broke ground on the resort in 2022, and it is scheduled to open next spring. The resort’s opening will create more than 400 jobs in southeast Oklahoma and will create an annual economic impact of $95 million for the region.”

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Chairman John “Rocky” Barrett, speaking during the June Sovereignty Symposium in Oklahoma City, said tribal operations are constantly growing.

“Medical, housing, commercial, government, infrastructure … we are expanding all of them,” Barrett says.

The tribe has 2,200 employees with about 200 jobs unfilled, Barrett says.

“We have increased wages up to 50% and still can’t fill jobs,” he says. “We will need to reach down into high schools and tech schools to augment training and work with unions on apprenticeship programs, to get skilled labor back in Indian Country.”

Female Leaders in Native America

“I want to be remembered as the person who helped Indigenous people restore faith in themselves,” Wilma Mankiller wrote in her autobiography, Mankiller: A Chief and Her People.

Mankiller was the first woman principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, doubling tribal enrollment and focusing on health care, housing and education during her tenure from 1985-1995.

Native women across Oklahoma continue her legacy by serving as elected officials and heads of tribal services.

Deborah Dotson, now in her second term, was the first elected woman president of the Delaware Nation. Women also serve the Anadarko-based tribe as vice president, secretary and treasurer.

Dotson, a former paralegal, started her political career in 2015 when she was elected as a committee person. After a couple of years observing the tribal president at work and not always agreeing with him, she said to herself, “I can do this. I can be president.”

Since she took office, tribal enrollment has grown by more than 700 due to drop

ping the blood-quantum requirement in favor of lineal descendancy. Burial assistance was increased from $3,000 to $6,000, and tuition assistance was raised from $3,000 to $6,000 per semester for non-Pell grant students.

After Terri Parton was elected president of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes in 2012, “everything we did was for the people,” she says. “We bought land. We did after-school programs. We went after a lot of grants. As long as your vision is all the same, the disagreements you can set aside.”

An Emphasis on Education

The Choctaw Nation is among many Oklahoma tribes that offer education assistance to citizens and employees, says Gwin. The career development department offers financial assistance to students seeking a certification or license through a college or vocational/technical school.

Choctaw Nation employees have access to $2,500 a semester in tuition reimbursement.

The higher education program helps tribal citizens pursuing degrees at accredited colleges and universities. Last year, Choctaw Nation provided more than 10,600 scholarships.

There’s also a one-time $300 payment for clothing purposes. More than 2,100 students received the college clothing allowance last year.

The tribe offers a one-time payment of $500 for technology purposes, Gwin says, and last year, more than 1,300 students receive a technology allowance.

The Concurrent Assistance Program offers financial assistance to qualified high school students attending an accredited college or university. Funding amounts are $200 for three hours of college credit or $400 for three or more college credit hours. More than 420 students received concurrent assistance scholarships last year.

The Higher Education Stole Program offers a Choctaw Nation stole valued at $53 to eligible graduating students.

“Last year, we distributed 690 stoles to graduates,” says Gwin.

The Chickasaw Nation has more than 6,000 tribal citizens enrolled in college.

“We help support them with scholarships to the tune of $28 million,” says Anoatubby.

The Native American Hall of Fame

James Parker Shield was just 19 when he met the person who would become his lifelong mentor. His name was Ernie Stevens Sr., and he’s now a member of the National Native American Hall of Fame. This citizen of the Oneida Nation was an advocate for Native rights and tribal self-governance who worked for a long list of social and political agencies; he was also the first staff director of the federal Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs.

“Ernie was my hero when I was in Washington, D.C.,” says Shield. “He took an interest in me, he encouraged me, he introduced me to people.”

Shield went home to Montana, studied history, started his own career and for 18 years was a board member of the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center.

And when he founded the National Native American Hall of Fame in 2016, it was people like as Stevens he had in mind.

“These role models that we have in the Hall of Fame, they can inspire younger Native Americans,” says Shields.

After a few years in Great Falls, Mont., the Hall of Fame has been moved to First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City. The invitation came from FAM director James Pepper Henry, and Shield says his board thought it was a great idea to move to a facility in the center of the country with a climate better suited for year-round tourism.

And the 39 tribes based in Oklahoma will always be well-represented as the Hall of Fame chooses board members and new inductees, says Shield.

The Hall of Fame opened in March in an ancillary building that was once a welcome center for FAM. Once the money is raised, a wing will be built to house it. Currently, admission to the Hall of Fame is free for people who don’t also visit FAM.

Induction ceremonies started in 2018 and have been held at FAM since 2021. This year’s induction is set for Oct. 14, and members of the 2023 class are government leader Joe DeLaCruz, Quinault Indian Nation; actor Will Sampson, Muscogee Nation; writer Leslie Marmon Silko, Laguna Pueblo; journalist Mark Trahant, Shoshone-Bannock Tribes; attorney Richard Trudell, Santee Dakota Sioux Tribe; and educator and activist LaNada War Jack, Shoshone-Bannock.

Other tribes in Oklahoma with citizens in the Hall of Fame include the Pawnee, Cherokee, Kiowa, Sac and Fox, Chickasaw, Comanche and Osage nations. Shield, who is Chippewa, says the mission has been expanded to include an educational outreach to secondary schools, and he foresees activities such as art exhibits and a symposium for Native writers.

Learn More:

At nativehalloffame.org, you can find photos and biographies of each of the people who have been inducted into the National Native American Hall of Fame since the first class in 2018. There was no induction in 2020.

Luminaries chosen so far from among the tribes in Oklahoma include Jim Thorpe, Maria Tallchief, N. Scott Momaday, Wilma Mankiller, Allan Houser, John Herrington, Wes Studi, Pascal Poolaw, Bill Anoatubby, Joy Harjo and Mary Golda Ross.

The mission of the Hall of Fame is to honor the achievements of Native American path-makers in contemporary society, starting with the Civil War period, in such categories as entertainment, government, science, education, communications, advocacy, business, culture and athletics.

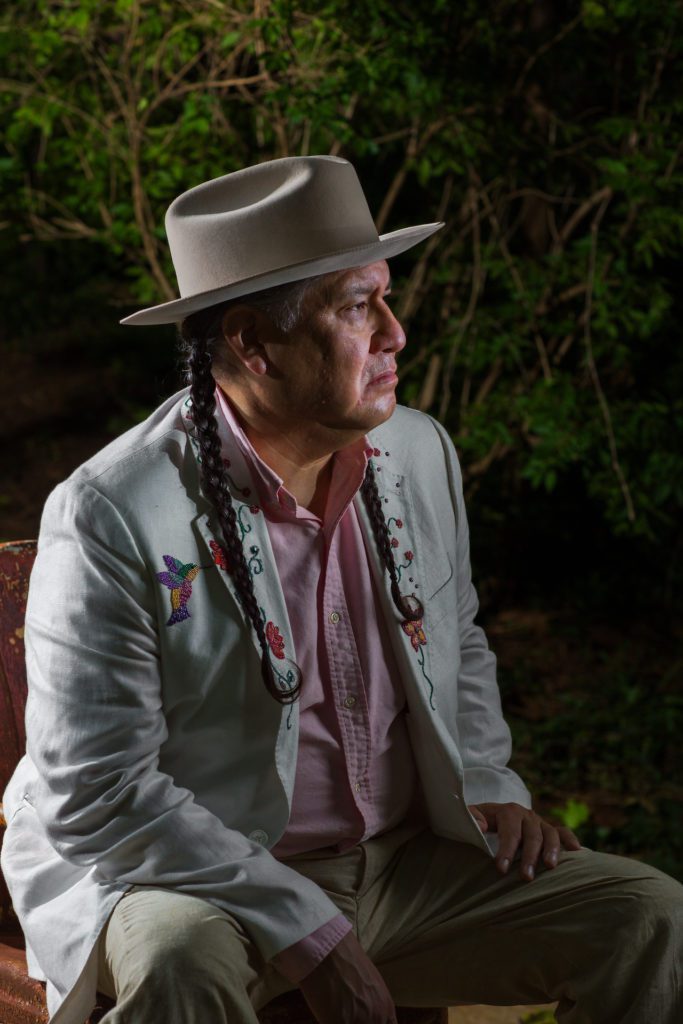

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: BONUS GALLERY WITH YANCEY REDCORN

Photos by Brent Fuchs