[dropcap]In[/dropcap] a league where the last player selected in the draft is called Mr. Irrelevant, undrafted free agents are considered long shots to even make an NFL team. They certainly aren’t expected to make it to two Pro Bowls, be named second-team All Pro and win a Super Bowl as a key player on one of the most dominant defenses in league history.

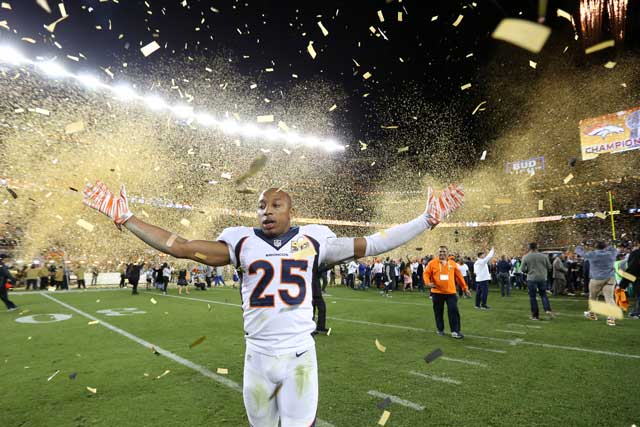

On Feb. 8, however, Bixby native Chris Harris Jr. watched confetti fall from the sky at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California, with the rest of his Denver Bronco teammates after their 24-10 victory over the Carolina Panthers. The Panthers had just finished a 15-1 regular season and were considered the favorites to win going into the game.

“It was an unbelievable feeling,” says Harris, who plays cornerback for the Broncos. “The way my team had to win the Super Bowl – everyone doubted us every week. We didn’t have any blowouts. Every game was hard, gritty, a fight. It wasn’t easy. It just made it even more special because of the way we had to fight to win.”

Being an underdog isn’t new to Harris. He has spent his whole life fighting to surpass expectations.

Building a Legacy

It’s impossible to miss the mark Harris left on Bixby High School. The street in front of the football stadium has been named after him since 2015, marking not only his impact on the school, but the continued love from the city 10 years after his graduation from high school.

“That was an amazing accomplishment right there,” Harris says of having the street named after him. “I just always wanted to leave my legacy, and I think having that right there is part of my legacy. I’m just thankful Bixby did that for me.”

Before Harris arrived, Bixby wasn’t a perennial high school football powerhouse in Oklahoma. With an enrollment of less than 1,500, the school was about half the size of traditional state champions schools. In 2004, the football team posted a 6-5 record. In 2005, the Spartans placed second in the Class 5A football championship.

“We made it a powerhouse,” Harris says. “My class and the class above me, together, we made it a powerhouse.”

The team went 12-2 in 2005 and 10-2 in 2006. Harris was named to the Tulsa all-metro first team both years and earned all-state honorable mention as a junior. He was named an academic all-state player in both 2005 and 2006.

Harris says one of the best things about playing for the Spartans was the sense of family. Many of the football players had been playing on the same team for years.

“Playing there was amazing,” he says. “It was cool because I had grown up with all the guys. All the players had grown up playing together from the fifth grade. That was one thing I loved about playing at Bixby, that we all got to play together from middle school up.”

Photo courtesy Chris Harris Jr.

After high school, Harris committed to the University of Kansas – while he wanted to stay in state, he didn’t receive scholarship offers from the University of Oklahoma or Oklahoma State University. The University of Tulsa offered him a scholarship, but only after he had committed to KU.

For someone used to playing an underdog role, the lack of interest from Oklahoma schools provided extra motivation.

“That always drove me in college,” he says. “I never understood why no Oklahoma schools wanted me.”

Harris finished as one of the most successful defensive players in KU history, ending up second on the all-time tackles list for the school. Despite his continued success from high school to college, though, Harris faced another tough road to the next step in his career.

A Long Offseason

The odds are against any college athlete making it to the professional level. In 2016, the NCAA predicts 1.6 percent of all college football players will reach the NFL. Harris found himself fighting even longer odds after not being considered an NFL-ready player by his coaches at KU.

“They had an NFL prospect list,” he says. “I wasn’t on the list, so I didn’t get any help from my coaches. We also had a lockout at that time, and since I went undrafted, I couldn’t be in communication with the NFL that whole offseason.”

The lockout burdened undrafted players trying to sign with NFL teams. In a normal offseason, teams may contact undrafted players immediately after the NFL Draft in spring. The lockout meant that Harris had to wait to talk to any teams that might be interested in signing him.

His undrafted status and the difficulties posed by the lockout didn’t daunt Harris. He went back to Bixy and stayed ready, even while other people told him to give up on his dream.

“I had to prepare and stay home in Tulsa, and I had tons of people tell me to just quit,” he says. “Give up on it. Get a job. I just kept working out and made sure I was ready to go.”

Harris kept working out and stayed in shape to play football, and his patience and perseverance were rewarded when he got a call from the Denver Broncos. From that moment, Harris says, he knew he was going to make it in the NFL.

“My mom and dad were supportive, still in my corner, and I was thankful for them for continuing to believe in me,” he says. “Once Denver called, my parents knew I wasn’t coming back home. Even though I ended up signing the lowest signing bonus on the team, $2,000, I was happy with that.”

While that signing bonus may not be much in the world of professional sports, what it represented was something greater: opportunity. Harris had a chance to make the roster and an opportunity to prove himself.

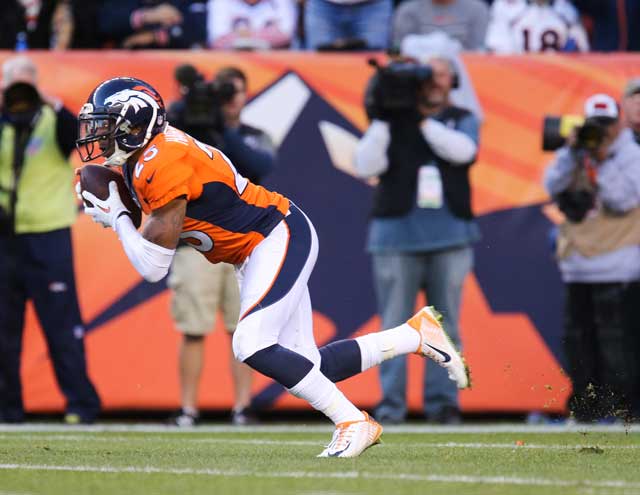

Photo by Eric Lars Bakke.

On the Field

In 2011, his rookie season, Harris lived up to the promise he showed in training camp by earning a spot on the final roster. He was one of four rookies to play in all 16 games for Denver that season, and he made the Broncos’ All-Rookie team and was named the team’s Breakout Player of the Year and Overachiever of the Year.

He built on that success in 2012 and 2013, starting 12 and 15 games, respectively, in Denver’s defensive secondary. The Broncos’ signing of future Hall of Fame quarterback Peyton Manning helped drive them to the playoffs both years. In the 2013 playoffs, however, Harris suffered another setback when he tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his knee, one of the most serious injuries in sports. The injury ended his postseason, but the Broncos made it to the Super Bowl before losing, 43-8, to the Seattle Seahawks.

“Coming back from an ACL injury, you never know how it’s going to be,” he says. “The rehab went great. I think I broke a record, coming back in seven months and starting a game. That was a big accomplishment for me because that was something I wanted to do. I knew it was going to be hard having the ACL surgery in February and then coming back and starting the season at corner.”

Harris didn’t miss a day of rehabilitation as he fought to make sure he would be ready for the next season – and while it was no surprise to anyone who knew Harris, he came back better than ever.

In 2014, he made the Pro Bowl and the Associated Press named him second-team All-Pro. The Broncos rewarded him with a five-year contract extension worth more than $42 million that December – a big accomplishment for an undrafted player who originally received a $2,000 signing bonus.

Last season, Harris was again selected to the Pro Bowl while serving as a key member of Denver’s defense, which allowed 283.1 yards per game, the best in the NFL. Although he was dealing with a shoulder injury, Harris managed to turn it up another notch in the playoffs, recording five tackles and a sack in the team’s Super Bowl victory.

“I wanted to have a great game in the Super Bowl,” he says. “I gave up 7 [receiving] yards. That was my goal, to go in there and shut down those Carolina receivers and [Carolina quarterback] Cam [Newton], so I definitely feel like I did my job helping the team win the Super Bowl.”

Exactly how well Denver’s defense did last season, however, came as a surprise to the team, who had to be corrected by President Barack Obama on a visit to the White House to celebrate their championship.

“We all thought we led in 14 categories, but then we went to the White House and Obama said we led in 19 categories,” Harris said. “That just made it more impressive, what we did last season.”

Off the Field

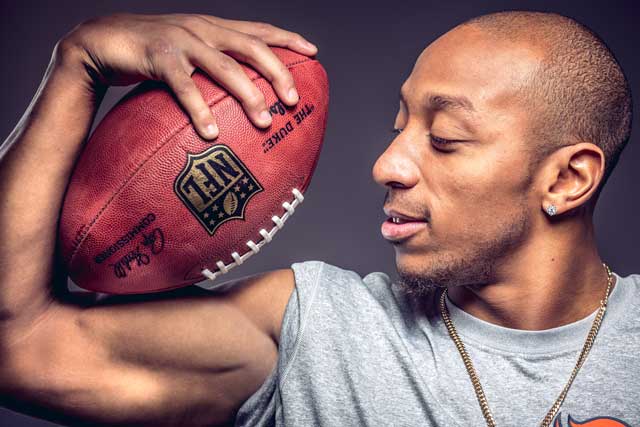

While Harris was finding success in the NFL, he was also living a full life off the field. In 2012, he married his college girlfriend, Leah, and in 2014 they had a daughter, Aria.

“Ever since I met Chris, I always said ‘perseverance’ was his middle name,” Leah says. “He would always joke and tell me he knew I would be his wife one day, and that’s the same attitude he has for everything. He has always claimed his success in his career and that really sets him apart from the rest. He doesn’t allow hurdles to get in the way of his dreams. That and his big, loving heart are my favorite things about him.”

Photo by Max Ralston

He has shown that heart in many ways, including working with Leah to set up the Chris Harris Jr. Foundation, which is dedicated to helping other underdogs. He holds an annual free football camp for children titled – what else? – the Underdog Football Academy. He has also been a spokesman for Domestic Violence Intervention Services, and his foundation has worked with organizations like Big Brothers Big Sisters of America and The Salvation Army.

“I started the foundation my rookie year,” Harris says. “I just wanted to always help out kids who are the underdogs and who want to do something in life, who want to always be active. That’s something we always try to preach to the kids. We preach anti-bullying. That’s just some stuff – we try to motivate them. We have kids in Texas, Oklahoma and Denver, and we just try to do whatever we can to make their lives easier and give them a head start.”

Always an Oklahoman

Although Harris and his wife live in Dallas during the offseason, he says Oklahoma will always be his home.

“Oklahoma – everybody knows I’m from there,” he says. “All my family is there. It’s where I grew up. Growing up in Oklahoma, being a country boy, I always loved it. I always come back home. I always get homesick. There’s always a time during the season where I can’t wait to get back to Oklahoma and see my family. There’s so much love there. I always love to come back home.”

Playing for Denver has made that trip a little easier for Harris. His family makes it to many of his games, and he says he always plays to a packed house when the Broncos play their game in Kansas City every season.

“It’s good, not being too far,” he says. “[Denver]’s about 10 hours away from Oklahoma, but shoot, my family seems to make that drive fairly easily.”

Harris continues to see more success in his future, both individually and as part of a team.

“We’re still hungry,” he says of Denver’s defense. “We still want to be a dominant defense, but to be able to do what we did last year — it’s definitely going to be challenging.”

And while Harris may be coming off a big season and a Super Bowl victory, he’s not planning to lose his underdog mentality anytime soon.

“I’ve never been first-team All Pro,” he says. “That’s something I want to do. It’s an accomplishment I haven’t got, so that’s my focus this year. I know if I’m a first-team All Pro, my team is going to be winning.

“I have an I-hate-to-lose, competitive nature and always try to prove people wrong. I think that’s really what drove me to be the player I am.”