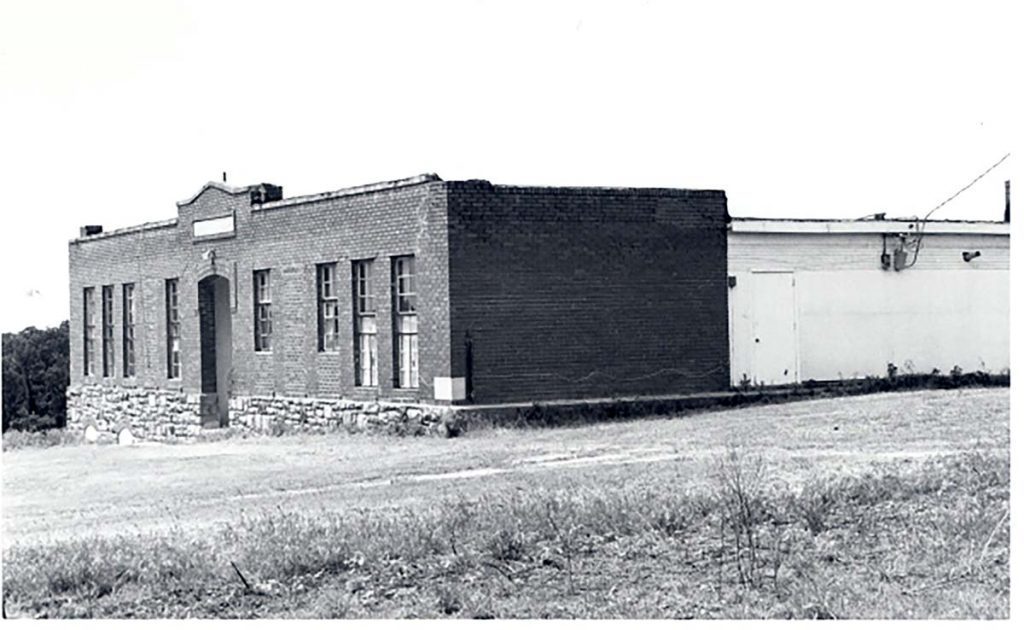

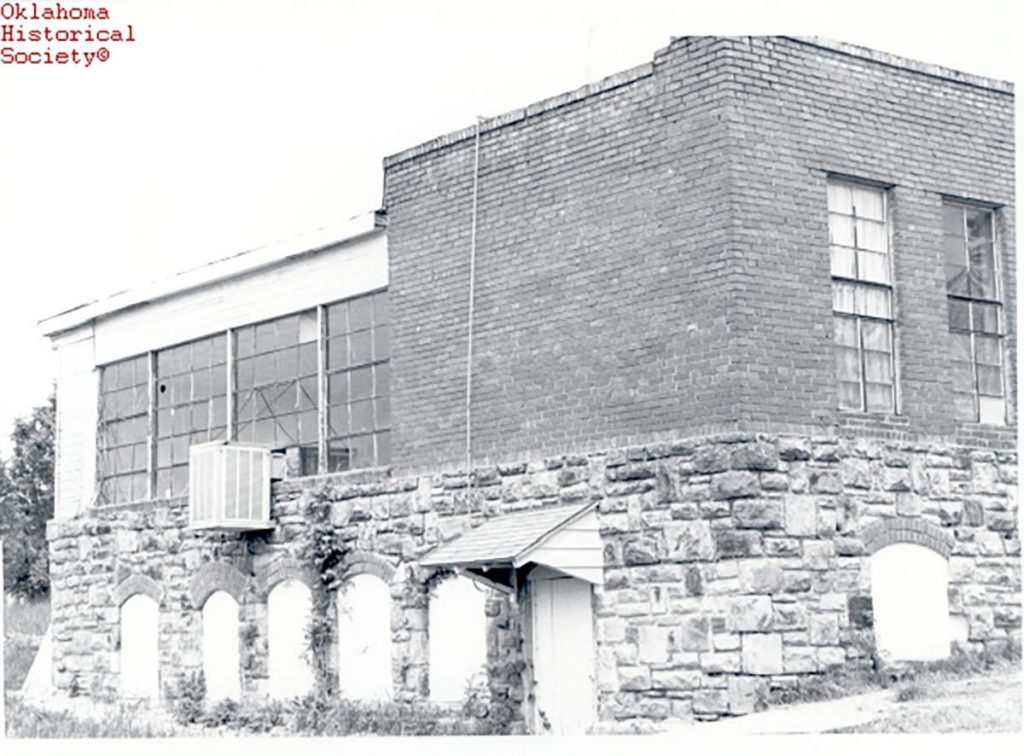

The rectangular building, gray and beaten with age, is barely distinguishable from the wild grasses that grow up around it – simply a smudge on a prairie that threatens to envelop it. In other locations exist mere suggestions of buildings – steps that lead nowhere, a part of a wall, a corner open to the vast sky.

Once, these stairs led small feet into a classroom and the corner supported a roof sheltering desks full of students and teachers not accepted in better-funded schools. These safe places once gave black students the chance to learn and grow just like their white counterparts.

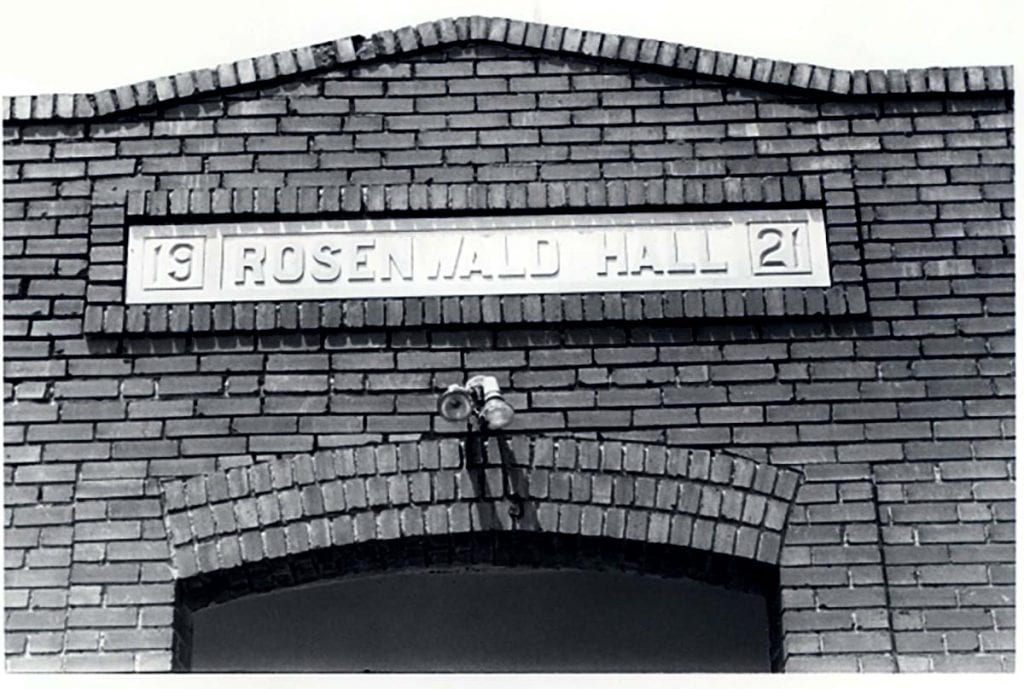

In the 1920s, nearly 200 schools and educational buildings in Oklahoma were built for African-American students and teachers as part of the vision of Julius Rosenwald. His namesake fund, created in 1917, helped to construct more than 5,000 one-room schools in the southern United States for underfunded communities; supported African-American artists and researchers with grants; and provided other educational opportunities for poor areas.

Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama steered Rosenwald, a philanthropist and the president of Sears, toward these projects.

“Rosenwald was a contributor to and served on the board of directors to Tuskegee,” says Larry O’Dell, director of special projects and development for the Oklahoma Historical Society. “Booker T. Washington encouraged him to build schools for African-Americans in Alabama before he started the fund.”

In the Jim Crow era, African-American students across the country faced unequal education, especially in the South, where schools were segregated. Black schools were chronically underfunded … or nonexistent. After Oklahoma became a state in 1907, segregation became the norm.

“The first law passed by Oklahoma’s legislature was a Jim Crow law, Senate Bill No. 1, which separated train cars for whites and blacks,” O’Dell says. “So, schools faced discrimination and a severe lack of funding in African-American communities.”

With Washington’s encouragement, Rosenwald set up his fund to provide educational support for African-American students. The building program ended in 1932 through instructions from Rosenwald, who planned a sunset date on his funds.

“Rosenwald did not endow this fund [as] he wanted to spend all the money, which it did in 1948,” O’Dell says.

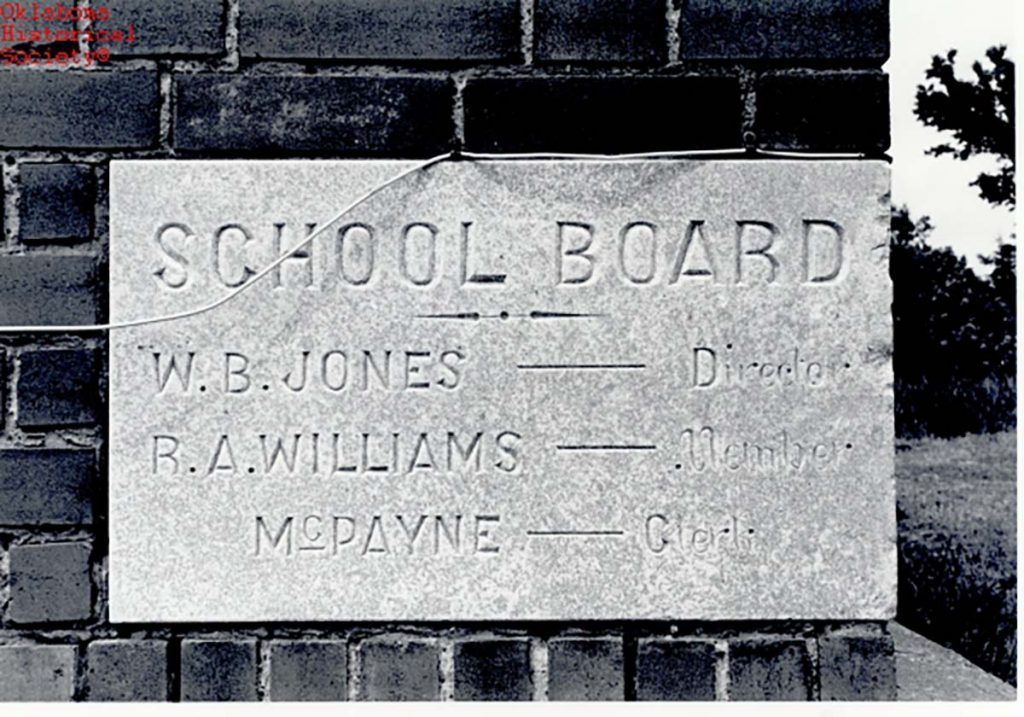

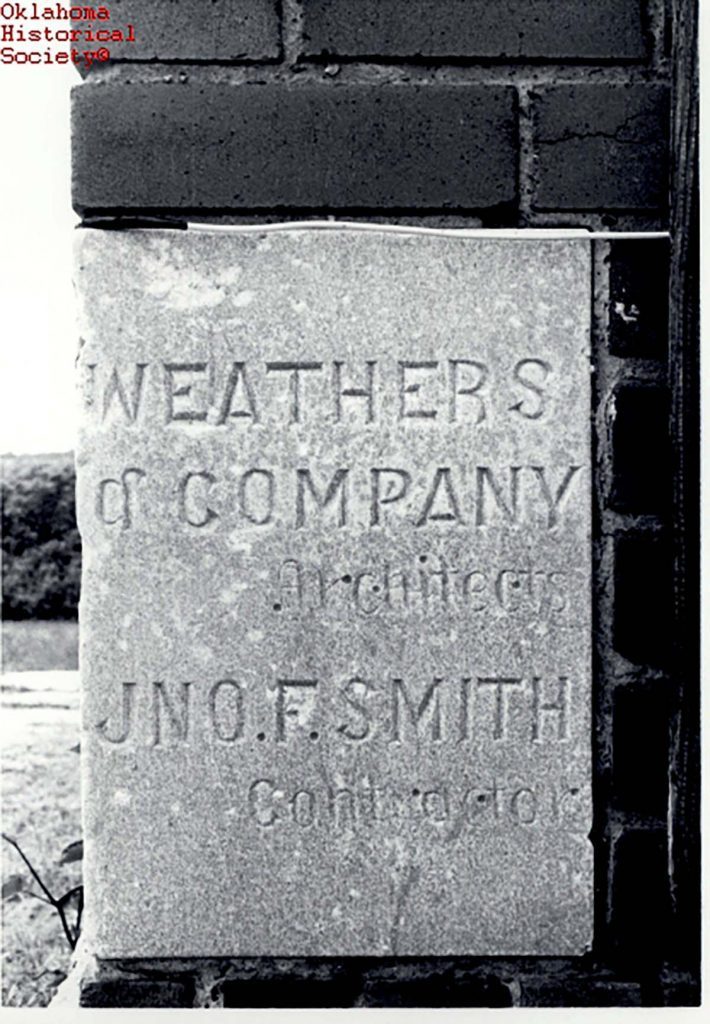

The fund didn’t bankroll the entirety of any single project but provided seed money to spur local groups – from both the white and black communities – to invest in education.

“It let the community get involved and gave them incentive to raise the rest of the money,” O’Dell says. “It was very successful in doing so.”

Due to the small size of many of these structures and the use of weatherboard as a building material, most schools are gone. Many were abandoned after rural districts began to consolidate in the 1940s – and they disappeared into the prairie grasses of history.