Nearly 500 years ago, philosopher Francis Bacon penned a notable phrase about finding alternatives. And it could apply – with a twist – to landlocked Oklahoma.

“If the Hill will not come to Mahomet, Mahomet will go to the hill,” the English statesman wrote in his famous collection, Essays. That take-charge approach is apropos to the Sooner State, home to the most human-made lakes in the country.

A perfect storm of factors explains why Oklahoma has more than 200 constructed lakes, nearly ranging from A to Z (Altus to Yahola). That number may seem odd given the state’s historical identity with drought and zero natural lakes of significant size.

After the devastation of the Dust Bowl, the state seemed to say, “If the Water will not come to Oklahoma, Oklahoma will bring the water to it.”

The lakes are a product of powerful politicians; ideal topography to dam numerous rivers, creeks and streams; federal funding of flood-control projects; and a cultural will to supply drinking water and irrigation to as many people as possible.

Earl Groves, recently retired after 10 years as chief of operations for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Tulsa district, says the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System is a perfect example of all the variables coming together to make water readily available to millions of people.

Oilman Robert S. Kerr (governor and thrice-elected U.S. senator) and Carl Albert (longtime U.S. representative and one-time Speaker of the House) used their clout to make the navigation system a reality.

“Many lakes are connected to and affected by that system,” says Groves, who spent 43 years with the corps. “It was the largest corps civil works project at the time. It created the most inland port in the country [Catoosa].

“Kerr and Albert had the foresight to make it good for everyone – municipal water supplies, agricultural irrigation, fish and wildlife, recreation and flood control.

“The planning began in the 1950s and, one after another, lakes came online before the navigation system went live on June 1, 1971. That’s the jewel in the crown.”

Before that massive project, national flood-control money funded many other Oklahoma lakes. Sites for dams were relatively easy to locate because, as Groves notes, the state has only two primary watersheds – the Arkansas and Red rivers. Rolling hills and plains created natural horizontal funnels throughout the state.

“You can’t dam a river in the wrong place,” Groves says. “It’s not politically smart. There was a joke among politicians that there was a race to see who had the most lakes, but that never happened.”

In the dry western part of the state, human-made reservoirs collect rain that forms over the Rocky Mountains and dumps in Kansas and Oklahoma.

In the relatively wet eastern part of the state, lakes prevent routine flooding. For example, Bixby and Tulsa’s Brookside became inundated whenever the swollen Arkansas River leaped its banks. Keystone Lake severely curtailed the number of floods.

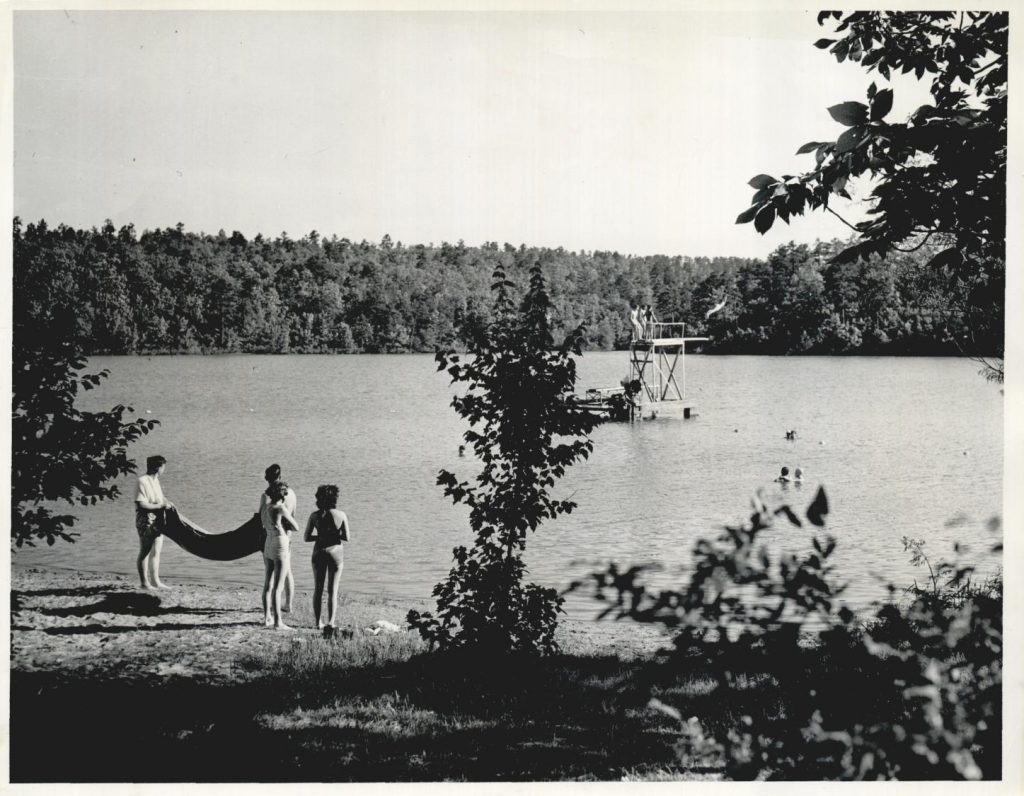

A prosperous byproduct of all these human-made lakes is outdoor activity.

“It was not an original intention to have tourism and recreation,” Groves says. “It’s now a multi-billion-dollar industry. These lakes have propelled our tourism, which is the No. 3 industry in the state.”