[dropcap]Poisoned[/dropcap] earth. Lumber communities that vanished with the forest, boom towns that dried up when the oil ran out. Railroads that never came, mines that failed in their promise of riches. Whether consigned to the dust or in the slow process of decay, Oklahoma’s abandoned communities and their tales continue to resonate. Some are still home to a few dedicated holdouts, waiting for a turnaround that never comes. Others have faded into memory and myth. All of them tell the story of our state. There are estimated to be thousands of towns that have come and gone over Oklahoma’s long history. Here are some of their stories.

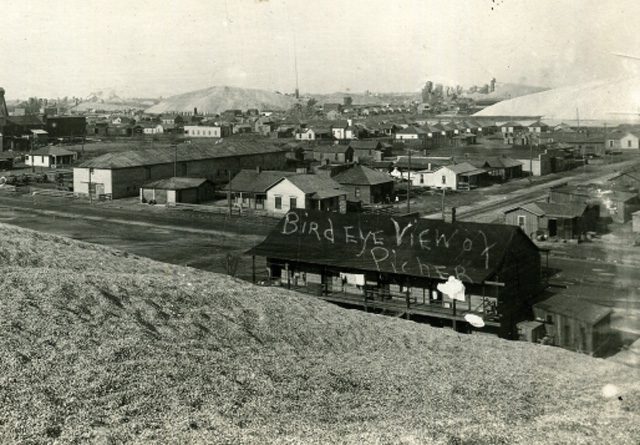

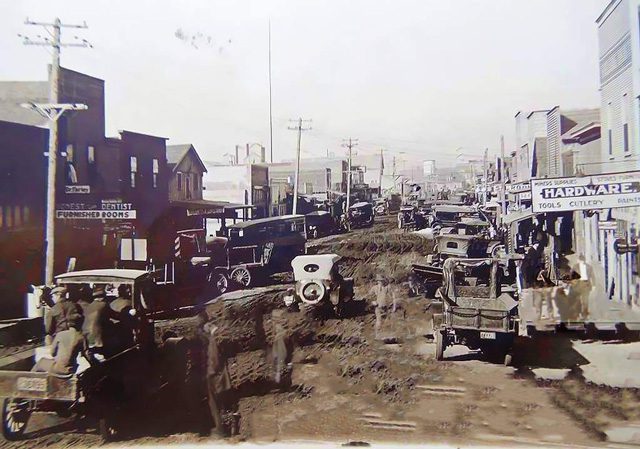

Picher

Picher wasn’t always known as Oklahoma’s toxic city. Nestled in the northeast corner of the state near the Kansas-Oklahoma line, it was once a flourishing town of 20,000 people, called the zinc and lead capital of the world. Residents used the massive chat hills surrounding the city as a recreational area, holding picnics and sled races, unaware they were frolicking on piles of poison. People joked about the orange water, polluted with the runoff of heavy metals from the mines, shrugged and swam in it anyway. Slowly, however, people in Picher began to realize something was very wrong. While mining closed down in the 1960s, people in the town showed alarming rates of cancer and learning disabilities. Infant mortality was high, and children tested with shocking levels of lead in their blood. Today, Picher is known as one of the most polluted locations in the country. As part of the Tar Creek Superfund Site, Picher has been the recipient of millions of government dollars in an effort to reclaim the poisoned land, to little avail. Toxic clouds of dust from the chat blow through now-deserted city streets and buildings. Mining tunnels under the town collapse to create massive sinkholes, some of which have swallowed multiple houses in one greedy gulp. As if Picher didn’t have enough problems, an EF4 tornado – the second-most destructive classification of tornados on the Enhanced Fujita scale – chewed through what was left of the town in 2008. The federal government, intent on buying out property owners to move them to safety, chose not to provide funds for rebuilding. As of a couple of years ago, fewer than 10 die-hard locals were holding out for better times in Picher.

Beer City

If you think things get crazy in the small towns of the Oklahoma Panhandle now, you’ve obviously never heard of Beer City. This den of outlaws and reprobates lurked in the No Man’s Land of what would become Beaver County, between the Texas Panhandle and Kansas. Sobriety-weary Kansans would flee prohibition in their state for the saloons and cathouses of Beer City, indulge in a Wild West show or boxing match, then sneak back home to Liberal, Kansas, with nobody the wiser. What happened in Beer City stayed in Beer City, and local merchants didn’t mind the town’s bad reputation; in fact, they banked on it. One man, either unfortunate or greedy depending on the tale you believe, tried to set himself up as sheriff of Beer City for a while. Whether Amos Bush had a genuine call to a law enforcement career or a less noble passion for kickbacks remains a mystery. What is known is that he met the business ends of several shotguns, and that was the end of the law in Beer City until it was officially incorporated into Indian Territory in 1890. The imposition of discipline and order took the shine off the town’s appeal. Beer City lived fast, died young and left no corpse at all. While a small unincorporated community still exists, nothing of the original hedonists’ heaven remains.

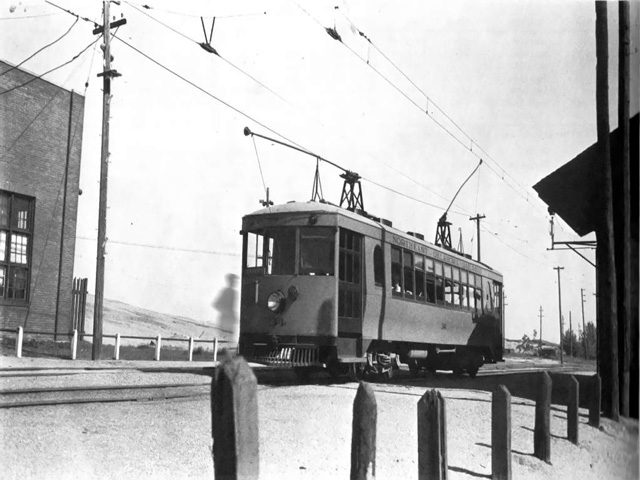

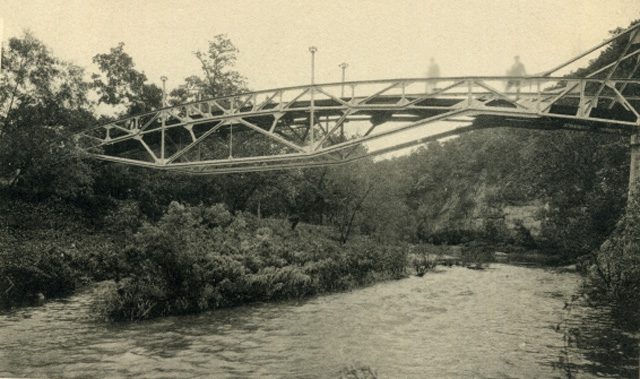

Bromide

In northeast Johnston County at the dead end of State Highway 7D lies what’s left of the town of Bromide. Known under various names before its incorporation in 1908, the town was eventually named for the high levels of bromine found in the waters of its “healing” mineral springs. Bromide built its foundations on quarrying limestone and running a brisk tourism business. Up until the 1920s, local railroads offered leisure excursions to the spa resort and its hotels, swimming pools and bathhouses. By the time the Great Depression hit, however, the taste for tourism dried up, and Bromide never became the hit that nearby Sulphur did. Today, you can still visit what remains of this town in the Arbuckle foothills: a few businesses, a church, several dilapidated residences and capped springs abound. The area is also home to several picturesquely creepy cemeteries that may be of interest to history buffs and the spook savvy alike. The ruins of a nearby Chickasaw boarding school, Wapanucka Academy, are now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Ingalls

The skeletons of one of the most notorious towns in Oklahoma history lie east of Stillwater in Payne County. Once, its streets clamored with doctors, stablemen, barkeeps and school teachers. Today, the town of Ingalls is mostly home to ruined buildings and reproductions of original structures, as well as a stone marker that reads:

In Memory of U.S. Marshalls

Dick Speed – Tom Houston – Lafe Shadley

Who fell in the line of duty

Sept. 1, 1893

By Dalton and Doolin Gang

The monument marks the spot of the Battle of Ingalls, a bloody brawl between U.S. Marshals and the Doolin-Dalton Gang, a.k.a. the Wild Bunch, the Oklahombres or the Long Riders. Disguised as “boomers” in covered wagons, law enforcement descended on the outlaw hideout town with plans to finally apprehend some of the West’s most violent gunslingers. It was a showdown that left five people dead within minutes. Strangely enough, the population of Ingalls today remains much the same as during its initial founding – some 150. As of last report, there was a regular schedule of activities at the Ingalls Community Center, including an annual reenactment of the battle that made the town famous.

Meers

At the turn of the 20th century, miners struck gold in the Wichita Mountains — or so they thought. A local resident claimed her chicken clawed up a “yuuugge” nugget of the precious metal, which raised the hopes of prospectors. It’s also rumored that two mining companies conspired to “salt” ˜– spray the mines with just enough gold buckshot to drive up business – the Meers area. Regardless of which stories you believe, a gold rush was on in Meers, and a feisty mining camp sprang up. During its golden age, the town was home to an array of merchants, doctors, a gold smelter and even its own newspaper. But by 1905, what gold there had been vanished, and so did the town of Meers. Today, all that remains of the original structures is one building, now known as the Meers Store and Restaurant. Most travelers journey down State Highway 115 not for a glimpse of the past, but for a taste of the burgers; the Meersburger, served in a full-sized pie tin, may be the most famous burger in the state of Oklahoma. The old building also houses the Meers Observatory, a seismograph placed by the Oklahoma Geological Survey to monitor the Meers fault line. You may not be able to explore any ruins, but visitors to Meers can at least fill their bellies before exploring the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge.

Cooperton

Founded in 1899, this former Kiowa County trading post wasn’t home to any outlaw shootouts. It never rang with the rough laughter of miners, and it boasts no memorable ghosts. Cooperton’s story is iconic in that, like so many Oklahoma ghost towns, it waited in hope of an economic boom that never came, and failed to flourish when the railroad passed it by for another town. At one time the town boasted medical personnel, a church, multiple schools and general stores, and a newspaper, the Cooperton Banner. Today, nobody is sure how many people remain; no more than 20 were counted during the 2000 U.S. Census. Relics abound, however, and visitors can find the ruins of several residences, the old church building, a defunct filling station, a bank dated to 1927, an eerie gymnasium and more. Cooperton’s remains lie near the intersection of State Highways 19 and 54. No promises are made for your safety, though – Cooperton’s remaining structures are quite literally crumbling.

Cowboy Flats – Pleasant Valley

Once part of the Unassigned Lands – so called because it was the only land in Indian Territory not assigned to a tribe – Cowboy Flats was a vast area near the Cimarron River used to (illegally) graze massive herds of cattle. The area was rid of opportunistic cattle ranchers and settled during the Land Run of 1889 (and slightly before, by some enterprising individuals known as Sooners), when it was rechristened as Pleasant Valley. For a while, however, there was nothing pleasant about it. The area was a popular hangout for cattle rustlers and outlaws, including the omnipresent Oklahoma bad boys, the Doolin-Dalton Gang, members of which owned unworked claims in the area. Things settled down after the turn of the century, however, and Pleasant Valley grew to include churches, several doctors, a post office and more. With the advent of the highway systems and automobile travel, however, life in Pleasant Valley slowly withered. By the 1940s, the post office there closed. Now all that remain are a few tenacious remnants of old buildings and houses in Logan County, northeast of Guthrie.

Slick

Like so many of Oklahoma’s abandoned communities, Slick started out as an oil town in the early 20th century. The arrival of the railroad made Slick a hub of shipping and market activity. Home to saloons and cafes catering to roughnecks, the town had some 5,000 residents at its peak. None of it was meant to last, however. Within 10 years of its founding, the railroad was abandoned. Today, around 100 people remain in the community, which is about 10 miles southeast of Bristow on Highway 16. Most residents are commuters to the Tulsa area. What is left of the town includes the collapsing L’Overture Public School, where chalkboards still bear the scrawling of past students and a derelict auditorium waits for an audience that will never come, and several abandoned residences and decrepit storefronts. As far as ghost towns in Oklahoma go, there is a lot in Slick for the intrepid (and safety-conscious) urban explorer to enjoy.

Boggy Depot

In 1837, resettled by the U.S. government, the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes founded the town of Boggy Depot in what would become Atoka County. Boggy Depot quickly became a center of commerce for the area, serving as a mail route between the west coast and the Midwest, and at one time was the temporary capital of the Choctaw Nation. Oklahoma’s first Masonic lodge was founded in the town, which also included hotels, a bakery and an apothecary shop, among other merchants. As lively as the Boggy Depot was, its tale is a familiar one. When the railroad was built through the nearby town of Atoka, Boggy Depot couldn’t compete and was slowly abandoned. Remains of the historical town include the home site of Choctaw Principal Chief Allen Wright, credited with coining the state’s name, and a cemetery containing Wright’s remains along with those of missionary Rev. Cyrus Kingsbury. During the Civil War, Boggy Depot served as a Confederate headquarters, and another local cemetery is home to the Confederate casualties from the Battle of Middle Boggy, fought in the area in 1864. Nearby is the area formerly known as Boggy Depot State Park. Funding for the park was cut by the state, but the recreational area is now maintained by the Chickasaw Nation.

Bathsheba

Rumors of a long-gone Oklahoma Amazon tribe of females, located somewhere between Enid and Perry, have persisted for decades. According to legend, the town of Bathsheba (also called Bethsheba) was founded in the early 1890s by 33 women who were having none of it – no males of any sort (including animals) were allowed in the town. Almost immediately, as the story goes, a dozen residents decided maybe this lifestyle wasn’t their thing at all and abandoned the fledgling city. Another story relates how one citizen was discovered with a razor and exiled because she brought an object of male influence to the town. Soon after the town’s founding, a brave (although possibly hyperbolic) Kansas reporter claimed Bathsheba was a real place, home to at least one woman whom he recognized. When ordered to return by his editor to gather more information, he found the town vanished. Over the past century, several newspaper stories and even a novel have been written regarding Bathsheba, but nobody, including Ghost Towns of Oklahoma author John W. Morris, was able to discover any proof that it ever existed. If you’re roaming the back roads of Garfield County some fall night, let us know if you find anything.