[dropcap]Culture[/dropcap] matters. Heritage matters. They’re lights from the past that illuminate the path to the future. Four Oklahoman Indian tribes are exploring new and innovative ways to pass their cultural legacies to the next generation.

“Heritage links us to the past. It makes you who you are. It’s all of the ancestors that went before us. That’s what’s critical to knowing who you are as an individual and what makes you that person today,” says Choctaw Chief Gary Batton.

Preserving the Language

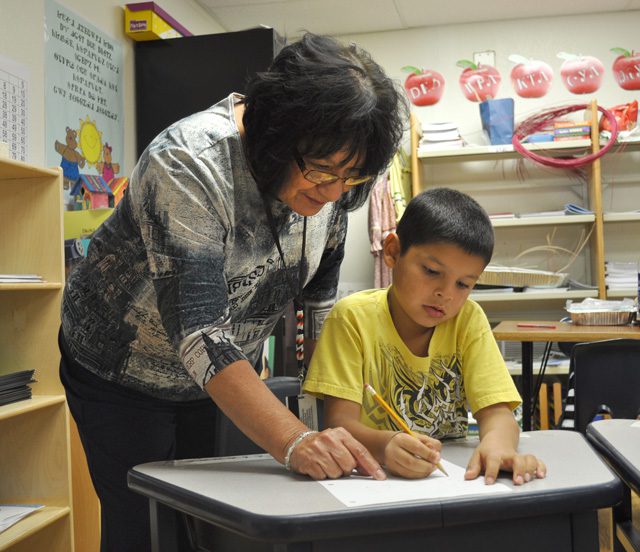

Language drives culture. Without language, culture can’t gel. To introduce the next generation to its culture, the Cherokee tribe starts with language. And it starts young with an immersion school for 3- to 8-year-old students.

“Our immersion school is one of the greatest things we have going in the Cherokee Nation. If I brought people to the nation and could show them only one thing, it would be the immersion school,” says Cherokee Secretary of State Chuck Hoskin.

The school serves about 100 students. The Cherokee language is used to teach all subjects, which is based on the the idea that kids learn languages more easily than adults. And the idea pans out; the school’s a runaway success.

“Probably the most important thing we do is our language program,” Chief Batton says. “A tribe without its language is considered lost.”

The Cherokee language is also available online and on smart phones. In the past year, the New Testament was translated into Cherokee. Other resources including dictionaries are available to those willing to learn.

The Choctaw Nation offers its language in Head Start classes and it is taught in high schools and various colleges. The nation also reaches beyond its geographic boundaries by offering Choctaw on the internet. On top of that, tribal elders who speak Choctaw are connected with eager students.

“We’ve always taken the position that there’s nothing more central to a people’s culture than the language itself,” says Joshua Hinson, language programs director for the Chickasaw Nation.

Hinson focuses his team on two goals. First, he wants to create a small cadre of truly proficient Chickasaw speakers that can in turn go out into the community and teach others. Second, he wants to make the language as widely accessible as possible.

Anompa, a Chickasaw learning program, is available on the web or through Apple’s iTunes store. Hinson’s department is also partnering with Rosetta Stone, the popular language learning company, to produce a product that can be used in schools or on the internet. Hinson also points to tons of published resources such as dictionaries, a teaching grammar, an official workbook, a children’s book and others.

Keeping Values Alive

“Heritage and history tie into our own unique identity as an indigenous people. Today we’re in Oklahoma, but what makes us unique in American society is that our ancestors had a relationship with other landscapes,” says Ian Thompson, the Choctaw tribe’s Tribal Historic Preservation Officer. “And that was over 100 generations. We developed a unique way of looking at the world, a unique language and a unique way of living. All of that still makes unique today even though we’re a removed tribe.”

You can tell a lot about a people by the games they play. Stickball, a traditional Choctaw game, was almost extinct until it was recently revived. Now it’s the national sport of the Choctaw Nation. But to many, it’s more than just a game.

“It can be a rough game, but it’s very much a game of honor. It’s a game of teamwork. It’s a game of giving and taking,” Batton says. “It teaches a lot of life lessons. Anybody can pick up the game of stickball. I think it would help them understand the human element of who we are as Choctaw – that we’re a good, loving, fun-spirited people.”

The nation’s Cultural Services department works hard to make the game available to kids. There’s a Choctaw national team. There’s a vibrant youth league. Tournaments are offered regularly, pitting Choctaw teams against those of other tribes that have picked up the sport.

“It’s a wonderful way to get youth involved in a healthy cultural activity,” says Thompson.

“We’re also doing things that instill our values – values like servant leadership, integrity and honor,” says Batton. “I think about Ireland, where after we came across the Trail of Tears and lost a fourth of our population, we turned around and gave money to the Irish that were going through the potato famine. We want to keep those values alive. We want to make sure that everybody knows that we’re a giving tribe. We’re a caring tribe. We’re really about sharing our hearts.”

National Treasures

No other tribe offers anything like the Cherokee Nation’s National Treasure program. Each year, the chief names two or three artists or artisans to be a national treasure. To qualify, their work must be of the highest quality, it must reflect Cherokee traditions and the artist must be committed to passing their craft on to the next generation.

Victoria Vazquez, a potter and national treasure, grew up watching her mother revive the craft of southeastern tribal pottery. Until then, Indian pottery was limited to Southwestern tribes. Over the years, Vazquez has taught hundreds of students her craft, and the art form is now alive and well in the Cherokee Nation.

The craft was almost lost following the Trail of Tears. Nobody pursued it until Vazquez’s mother did the research and taught herself. It was no easy feat. It involves digging your own clay, hand-processing it and wood-firing it outdoors, and it requires an extensive knowledge of traditional Cherokee designs.

“Pottery is now very much alive and well,” Vazquez explains. “After mom became well-known for what she was doing, she started teaching people. Then other Cherokee artists picked up on the idea that we should be promoting our Southeastern designs because most collectors only recognize Southwestern tribes as making pottery. Now other artists use them, for instance, in paintings or basket weaving.”

There are 45 national treasures in the Cherokee Nation. They include artisans teaching everything from graphic arts and contemporary art to music, storytelling and the Cherokee language. In all, about 15 traditional crafts are passed along to young Cherokees by the national treasures.

“It’s the highest honor that an artist or artisan can receive from the Cherokee Nation,” Hoskin says. “I can tell you that I’ve seen their work, and it is high quality. The idea is to honor these artists for their commitment to the arts, but we also hope that it inspires younger people to take up these art forms. Over history, we’ve come close to losing a lot of our art forms.”

Pottery is a priority for the Choctaw Nation, too. For six years, pottery classes have been taught to thousands of people. Many of the original students are now teachers.

“There’s a connection between us and the earth,” Thompson says. “There’s no more concrete expression of that than our pottery.”

Exploring the Past

“Culture decides who we are as a people, and if we don’t share it with the next generation, it’s going to go away. It defines who we are as a nation,” says Chinae Lippard, an archaeologist with the Chickasaw Nation.

Lippard’s found a unique way to pass along the tribe’s cultural heritage. Archaeology isn’t just a doorway to the past. It can be a window into culture. Lippard is working in conjunction with various universities to preserve important Chickasaw cultural sites in the Blackland Prairie, the tribe’s original home. Each year she conducts Homeland Tours where she offers Chickasaw students and leaders a firsthand look at their culture.

“It’s amazing. You can see it on their faces when they first go out there and make that cultural connection,” she says. “It’s a spiritual thing for them. They say, ‘Oh my goodness, this is where my ancestors came from. This is my land.’ They get really excited about it.”

Cultural Centers

The Chickasaw Cultural Center provides a learning experience not just for tribal members, but for the general population. The large campus in Sulphur offers something for everyone. Every day, live demonstrations of Chickasaw dance, beading, finger weaving and drum making provide visitors with an interactive entrance into the tribe’s culture. They can even make bows and arrows or stickball sticks.

“We welcome everyone to come and visit us. There’s a lot here for people to learn who we are,” says Valorie Walters, Executive Officer of the center. “Through our research center here, we have wonderful collections that are here. A lot of those go on exhibit so people are able to come in and learn about whatever’s up at the time.”

The center is also a great place to have lunch. Visitors can explore traditional Chickasaw food. It’s as much a part of the tribe’s culture as traditional crafts, music and dancing.

“As you go through our exhibit halls here, there’s so many interactive items for people to really engage with, whether it’s video or language station. Our visitor services team here can answer any questions about Chickasaw history and culture,” Walters says.

Cultural events at the center are celebrated all year long. A popular event is the Three Sisters Celebration, which celebrates traditional food. The three sisters are corn, beans and squash, and the tribe honors them during the spring planting season.

The Choctaw Nation wants to make traditional foods more popular. They’re healthy, they’re natural, and they’ve been proven for hundreds of years.

“Today, Native Americans suffer the highest rate in the country of diabetes, obesity and stroke. These diseases were almost unknown to us before colonization, when we lived our traditional ways,” says Thompson. “This connects us with the past, but by changing our diets we have the opportunity to overcome a lot of these diseases that we face at epidemic levels.”

Photos by Amanda Rutland, Muscogee (Creek) Nation Office of Public Relations.

Song and Dance Traditions

Song and Dance Traditions

All cultures are unique, but the traditions of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation are distinctly different from other Native American nations. It presents unique challenges.

“When you mention being an American Indian, people put you in feathers with a drum. Our culture is totally different from that,” says David Proctor, Cultural Advisor for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Preservation Program.

Recognizing the importance of music and dance as traditions, the nation makes a strong effort to give them to the next generation. It puts teachers in its communities to teach kids the traditional songs and the unique “stomp-dancing” of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Classes meet weekly, and they’re well attended.

“This is important for the survival of our tribe. Plain and simple,” Proctor says. “Without our traditional ways and culture, without passing our heritage on to other people, our identity as Muscogee people will fade away and we’ll be like everyone else.”

Growing the Herd

Courtesy of the Cherokee Nation, the bison is making a comeback on the Oklahoman plains. The tribe works with the National Park Service and various intertribal organizations to obtain bison. Over the space of a few years, the herd has grown to 100 animals. It recently grew by 12 calves.

The Cherokee are looking at ways to use the bison in the tradition of generations past. The animal provided food, shelter and other forms of sustenance to the tribe.

“The bison are a great success story,” says Hoskin. “Our history with the bison goes back many generations. They’re significant to a lot of native peoples, and they’re significant to us. We’ve got a good, healthy herd. We’ve got a wonderful area in a rural part of Delaware County where people can see the bison. We’re very proud of it as a way of reconnecting with our history.”

Four Oklahoman tribes. Several unique ways of passing traditions and heritage to the next generation. They’re proof that culture is a living thing, not just a ghost in the past.