Sam Harris may be the ultimate show-biz hyphenate.

It’s hard to believe that some 37 years have passed since the Sand Springs native brought down the house, and the whole country, on the TV talent show Star Search, leading to a recording contract, hit songs and a string of full-length albums. That’s when the hyphens began for him: singer-television performer-major-label recording star.

Over the subsequent years, he’s compiled more and more credits in all kinds of entertainment fields. He’s been an award-winning Broadway performer, TV producer, songwriter, scriptwriter and even an in-demand television talk show guest. Then, in 2014, he added “author” to that list, when Simon & Schuster’s Gallery Books brought out his memoir Ham – Slices of A Life.

What’s left to hyphenate for Harris? Well, how about “novelist”?

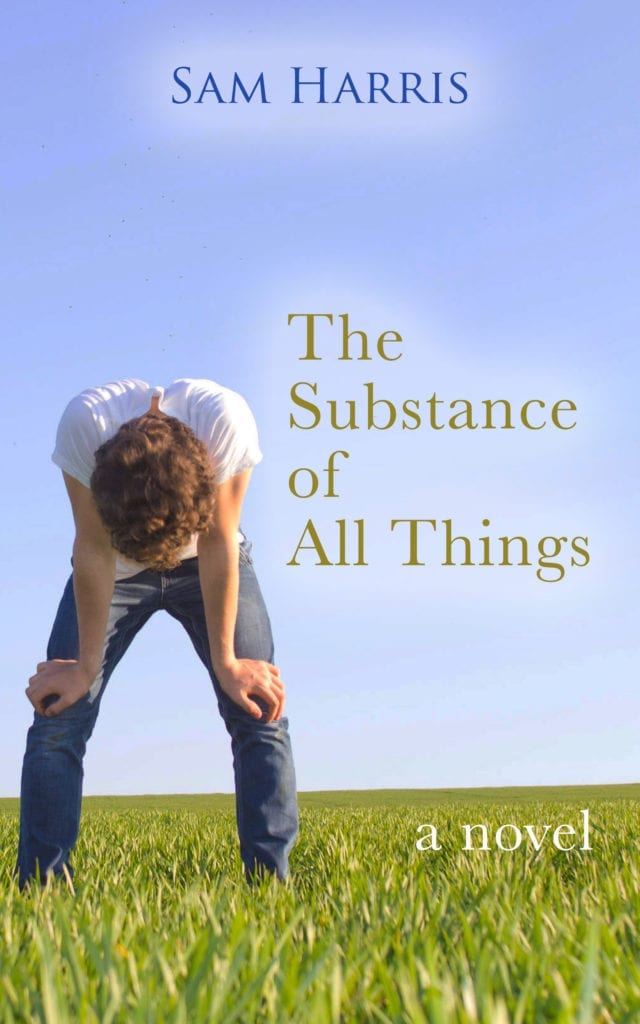

That’s what he’s become with the publication of his new book, The Substance of All Things, an often harrowing, beautifully realized story about an Oklahoma boy who, after suffering a horrendous automobile accident, finds that he can heal with his broken hands. Unlike Ham, The Substance of All Things is fiction. However, as Harris notes, his protagonist’s town of Dalton is based on Sand Springs, and some of the scenes and characters in the novel come out of his specific past – including a memorable minister who make his appearance early in the book.

“We had a pretty theatrical preacher at Broadway Baptist [in Sand Springs],” recalls Harris with a chuckle. “He was fire and brimstone, and he held the Bible up and he’d turn red. It was very exciting. He’d had several heart attacks, and you were always thinking, ‘This is the moment. He’s going to die right now. This is the big one.’”

“I think a lot of artists can talk about that moment: ‘

Oh. That’s it. It’s been waiting there for me to discover.’ It just clicks.”

So, while The Substance of All Things is definitely a work of fiction, Harris’ own experiences as a youth form the book’s mise en scene, to use a term from theater and film.

“The way the town looks, the way the buildings are – we write what we know, and I know what the culture was like,” he explains. “I know what the air felt like. I know the colors of the sky. The references that I make to the environment, and the people, and the colloquialisms, and all that stuff, that’s from my childhood.”

It was reacquainting himself with his childhood that finally led to the breaking of a year-long writer’s block, which followed his editor’s suggestion that he try writing a novel. But even before the block came, the simple notion of committing to a full-length work of fiction was burden enough.

“It was something that had always been at the back of my mind, but it seemed so daunting,” he says. “It seemed so large. The idea of a novel is very different from a collection of essays [as with Ham].

“So it was very intimidating, the thought of it. My editor had thrown me a couple of ideas about what he thought I should do, but it didn’t fit with me. So I had a block for a year. I’m not really a writer’s block person. Pretty much when I engage, the river flows. But this just would not come. I think I was overwhelmed and afraid of what it was supposed to be.”

Then, one evening a few years ago, at a dinner party, he told a friend about the trouble he was having breaking his block.

“He began asking me questions about my childhood, just to get my brain going,” says Harris. “And I remembered this short story I’d written, which no one had ever read, that was about a particular personal time in my life. And then, as I was talking to him about my childhood in Oklahoma, all of a sudden the concept, the seed of it, just hit.

“I think a lot of artists can talk about that moment: ‘Oh. That’s it. It’s been waiting there for me to discover.’ It just clicks.”

Unwilling to let any more time pass, Harris asked for a legal pad and then, he says, “While everyone else was in the dining room, I sat in the bedroom and started making notes.”

He admits to not knowing initially where he was going with the story, or what was going to happen. But he did have his protagonist, an adolescent boy named Theo Dalton, whose gift for healing with his hands gradually turns into an untenable burden.

With a narrative structure that alternates between young Theo and the present-day adult Theo, The Substance of All Things skillfully hints about its protagonist’s fate without giving anything away. The current Theo is a therapist – “a healer in another way,” Harris notes – and his interactions with a deeply challenging female client provide, as Harris puts it, “the conduit for the depth with which he explores his past.”

He adds, “I hate to use the word ‘channeling,’ because it sounds so clichéd. But sometimes when you’re writing a character, and you finish a part, you think, ‘I didn’t know that was going to happen.’ You don’t remember writing it. You don’t know that it’s happening as it’s coming out. You just know that it happened – and it’s a great feeling.”

Sometimes, also, an author writes something that resonates even more later, well after it was first put down on paper. Harris couldn’t have seen the pandemic coming when he was penning The Substance of All Things, but what Theo’s client has to deal with seems as timely as tomorrow.

“This woman, who has a condition called haphephobia, cannot be touched,” he says. “It physically hurts her, so she’s cut herself off from the world. It’s this idea of touching and being touched, the isolation of people. When she’s talking to Theo early on, she says, ‘You know, it’s really easy not to have contact with people. You can order everything in. You don’t have to go out.’ And here we are now, living in this world, where the lack of human touch has a lot of fallout.”

During the four years it took Harris to write the novel, his editor at Gallery Books was let go, so Harris made the decision to release The Substance of All Things independently.

“I said to my agent, ‘I want to have a conversation about this. More than 50% of the books on Amazon, both print and Kindle, are indie books. And it’s going to take six months to sell it – if we sell it – to a big publisher. Then it’ll take a year for their process and editing before we get a publishing date. Right now, we’re in COVID, and people are home. People are reading. People are investing in themselves. This book is about healing. I don’t want to wait.’ So we’re going for it.”

The Substance of All Things adds still another hyphenated entry to the long chain that follows Sam Harris’ name. It may, he says, be the hardest-won title of them all.

“Of all of the mediums, the things I’ve worked in, this took the longest for me to get there and required the greatest depth,” he muses. “I mean, you hear about a movie taking 10 years to make, and it may have taken that long to get it financed, but I’ll guarantee you it didn’t take 10 years to write. The script was written in a couple of months, maybe a year, and the rest was process and business.

“With a book,” he adds with a chuckle, “if you hear someone took 10 years to write it – it took 10 years to write it!”