[dropcap]The[/dropcap] road to athletic stardom is an uphill climb. To reach the pinnacle of their sport, athletes face challenges that test their abilities, both physically and mentally, each striving to be the best at what they do. Pioneer athletes such as Bill Spiller faced even bigger challenges that no measure of athletic ability could surmount.

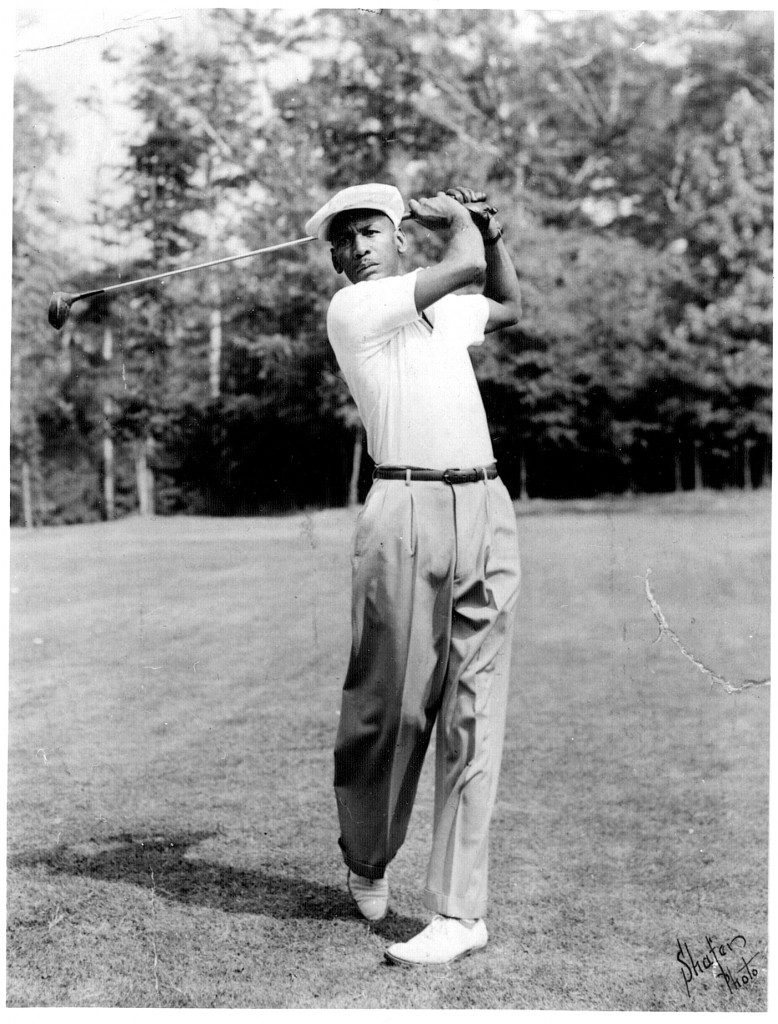

Born in Tishomingo in 1913, Spiller grew up in a world that was two decades from Jessie Owens in the Olympics and three decades away from Jackie Robinson’s breaking of baseball’s color line. Though a great all-around athlete at Tulsa’s Booker T. Washington High School and Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, it wasn’t until Spiller was 29 that he started playing the sport of golf.

Spiller proved to be a quick study and in 1947, the same year Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers, he started playing professionally. At the time, Spiller did not know of the Professional Golf Association of America’s Caucasian clause requiring all players to be white. Spiller did not lie down and accept his fate, but rather fought against an injustice that prevented him from playing professional golf and prevented others from working as professionals at clubs around the country.

Along with fellow golfer, Ted Rhodes, Spiller fought to right the injustice of the Caucasian clause through the public and through the legal system. Though Rhodes was the first and possibly best known of the African-American professional golfers at the time, Spiller had the tools to stand out: a college-degreed player, all-around athlete, teacher, caddie and club maker.

“He was the real deal,” says Del Lemon, author of The Story of Golf in Oklahoma. “As an amateur competitor, his rise was meteoric. On California’s west coast, he set numerous course records and won virtually all the events on the United Golf Tour, where black golfers were allowed to compete.”

Barred from the majority of PGA sponsored events, Spiller played where and when he could. He continually challenged the rules of the PGA and its tournaments despite facing racism, both obvious and obscure, along the way.

In 1961, Spiller’s efforts came to fruition and the Caucasian clause was removed by the PGA. But, in many ways, it was too late for the then 48-year-old. The PGA and most golf fans would never see him play at the peak of his career.

[pullquote]Spiller’s lawsuit knocked down a terrible, impenetrable wall,”[/pullquote]“He would have made an exemplary member of the PGA and possibly a huge draw to the game, perhaps the original Tiger,” Lemon says. “All he wanted was the opportunity to prove himself and make a living in the game for his family.”

With his best days behind him, Spiller would occasionally compete in tournaments and give golf lessons as he raised a family. Despite being a pioneer in the use of video as an instruction tool, Spiller’s legacy would recede into obscurity over time for many golf fans.

In 2009, 21 years after Spiller’s death, the PGA bestowed a posthumous membership to Spiller.

“I think the PGA did its very best, albeit much belatedly, to right an egregious injustice that denied a champion access to a career in golf because of its own institutional racism,” Lemon says.

On October 25, 2015, Spiller was inducted into the inaugural class of the Oklahoma Golf Hall of Fame. He has also been nominated into the World Golf Hall of Fame. A century after he was born, the Oklahoma native is now receiving recognition for his accomplishments on and off the course.

Lemon remembers. “Due in large measure to what Bill Spiller fought against and ultimately defeated, Tiger Woods never had to hear a PGA Tour official say, ‘Sorry Mr. Woods, but you have been disqualified. We have a whites-only membership clause on this tour.’”