I thought I was using myths to write a story. Turned out that I used a story to write a myth. – S.E. Hinton, from her author’s note for the 2013 edition of Rumble Fish

[dropcap]Forty[/dropcap] years ago, a full-grown child arrived in this world – brilliant, but destined to be misunderstood. It was Rumble Fish, the third novel from Tulsa-based writer S.E. Hinton. Like her previous two, The Outsiders (1967) and That Was Then, This Is Now (1971), the book was aimed at teenaged readers, a group that would come to be known as the young-adult market.

In fact, many say that Susan Eloise Hinton invented the young-adult literary genre. Certainly, The Outsiders made her its first major star. A teenager herself when she wrote it, Hinton came up with a debut novel that offered an unflinching look at young have-nots and their lifestyles (which included alcohol and gang fights), their friendships, their often-dismal home lives and their conflicts with the haves – delineated by Hinton as “socs” – as opposed to the lower-class “greasers.”

Hinton’s heart lay clearly with the greasers – those kids outside the prevailing socioeconomic system who will likely stay there forever – and her compassionate approach and deft, gritty writing resonated with junior high and high schoolers all across the world. After all, what teen hasn’t felt like an outsider at one time or another?

The Outsiders launched Hinton as a major literary force, and fans eagerly snapped up her next three books, also dealing with marginalized kids: That Was Then, This Is Now, Rumble Fish and Tex (1979). Each of these novels would, like The Outsiders, be made into theatrical films during the decade following their publication.

Of this Hinton quartet, Rumble Fish, both book and movie, is the most challenging – and, maybe, the most rewarding as well. First published in 1975, it’s the story of a young, not-too-bright outsider named Rusty James, who lives with his hopelessly alcoholic father and near-mythical older brother in a squalid apartment. Both go absent for long periods of time, and while Rusty James and his dad share an unbridgeable emotional distance, Rusty James idolizes his brother, a larger-than-life figure known only as the Motorcycle Boy. The book is narrated by Rusty James, which, Hinton tells us in her author’s notes for the latest edition, was a “very hard choice” that forced her “to stay in the character of a simple person and tell a very complex story.”[pullquote]As a writer, I’m most proud of Rumble Fish, because it’s very straightforward, there’s no foreshadowing.[/pullquote]

It was a choice worth making. By seeing all the action related in a direct, spare and sometimes uncomprehending way – some things Rusty James just doesn’t understand and can’t articulate – the reader is free to layer the basic narrative with his or her own interpretations and insights, getting at the big picture even when Rusty James does not.

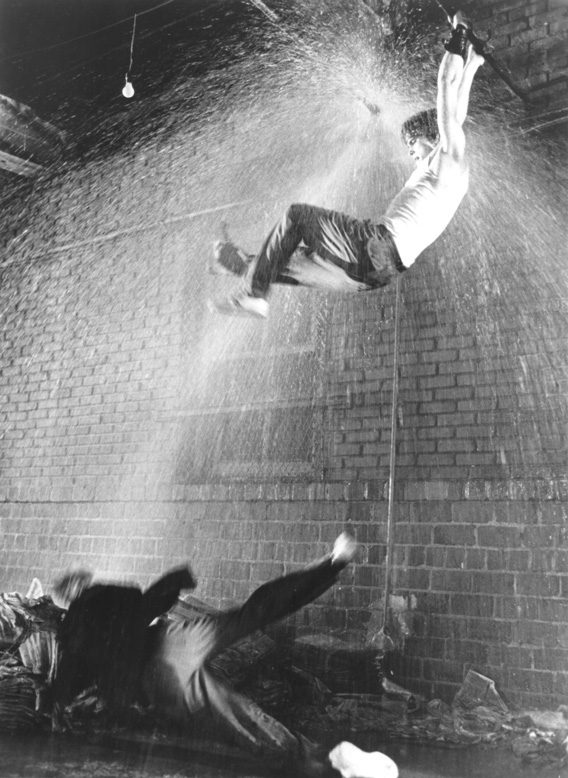

And there’s a lot of picture to get at. As the author’s-note excerpt atop this column suggests, Rumble Fish resonates with the qualities of myth, including dream states and flirtations with the supernatural. The Motorcycle Boy is a tragic figure right out of ancient Greek theater, done in not by pride, as those characters usually were, but because of a thwarted desire to rise above his surroundings. He and Rusty James and many of the other characters, including their dipsomaniac dad, are trapped in a kind of false freedom; for at least one of them, the ultimate realization of its inescapability leads to destruction. Like the characters in Bruce Springsteen’s classic rocker Born to Run, the Motorcycle Boy can roar up and down the highway until hell freezes over, Dad can drink until he passes out, and Rusty James can defeat one challenger after another, over a pool table or out back with his fists. But when it’s all over, they still have to return to their same squalid room and forlorn lives.

“As a writer, I’m most proud of Rumble Fish, because it’s very straightforward,” Hinton told Teresa Miller for the interview section of Hinton’s book Some of Tim’s Stories (2007). “There’s no foreshadowing.”