[dropcap]An[/dropcap] attentive reader might wonder why I’ve now done two columns in a row that have to do with the city of Claremore. Maybe it’s subconscious. I grew up in Chelsea, 18 miles down Highway 66, and Claremore was the place where we went to have fun. So perhaps on some subliminal level I still think of Claremore as an entertainment paradise worthy of continued exploration.

[dropcap]An[/dropcap] attentive reader might wonder why I’ve now done two columns in a row that have to do with the city of Claremore. Maybe it’s subconscious. I grew up in Chelsea, 18 miles down Highway 66, and Claremore was the place where we went to have fun. So perhaps on some subliminal level I still think of Claremore as an entertainment paradise worthy of continued exploration.

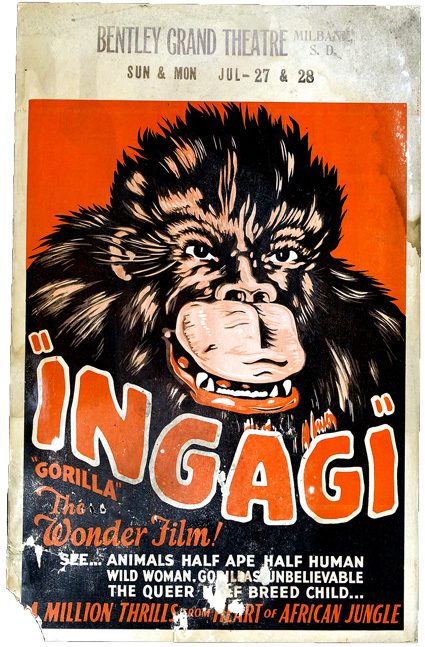

More likely, though, it’s just serendipity. For last month’s installment, I wrote about how Claremore’s great playwright and poet, Lynn Riggs, had finally gotten his due in his hometown. And I’d no more than finished that piece when I ran across a column in the Claremore Progress by Larry Larkin, my friend and collaborator (on the book J.M. Davis Arms & Historical Museum, along with Wayne McCombs). A part of Larry’s “Remembering Back When . . .” series, it was about a long-ago run-in between a visiting lecturer and some local boys he’d hired to help publicize his appearance. The man, who called himself Leon Dillingham, had been in town to appear at the local movie theater with an African-safari feature called Ingagi.

That got my attention.

[pullquote]Congo Pictures really bit off a lot more than they could chew,” Price says. “They were not counting on the controversy from the scientific community.”[/pullquote]As a lover of ancient, offbeat movies, I knew how notorious Ingagi had been, and how much of an effect it had improbably exerted upon the nation’s popular culture of the time. I had first run onto the title in a book by another one of my friends and collaborators, Michael H. Price of Fort Worth, Texas. In Forgotten Horrors, a groundbreaking work first published in 1979, Price and collaborator George E. Turner wrote in detail about how this alleged documentary from 1930 had been cobbled together by “an old-time circus impresario” and independent film producer named Nathan M. Spitzer.

Spitzer combined, without bothering to get permission, scenes from an actual 1914 safari picture called Heart of Africa with patently bogus new stuff shot in California, featuring a soon-to-be-legendary portrayer of gorillas named Charles Gemora running rampant in an oversized ape suit.

“Although it was all supposed to be in Africa, [Spitzer] took that footage from Heart of Africa and added soundstage stuff, mixing in flora and fauna of the New World,” notes Price. “But, gosh, when you look at the footage of Charlie Gemora on the rampage, it is powerful stuff.”

Released by an independent outfit called Congo Pictures, Ingagi also features a reptile, as Price and Turner wrote, that’s allegedly “so venomous it cannot be brought to civilization.” In fact, this horrifying creature is a customized African leopard tortoise, which the filmmakers covered with the armor of a scaly anteater, gluing on a pair of laminated bird wings for good measure. That creature led to the film drawing a resolution of protest from the American Society of Mammalogists, one of several groups that piled on the supposedly factual picture.

“Congo Pictures really bit off a lot more than they could chew,” Price says. “They were not counting on the controversy from the scientific community.”

That also goes for the film’s narrative thread, which has to do with mating between gorillas and humans, presented in a way that would be wildly offensive not only to scientists, but also to today’s moviegoers. However, in 1930, Boy Scouts and other school-age children were invited by some theater owners to view this “educational” picture at special screenings.

And that’s a good place to segue into the Claremore engagement of Ingagi. It’s not known if the Oklahoma youngsters involved were promised tickets or their own preview by the visiting Leon Dillingham; what is known is that Dillingham arrived in town via train sometime in late August of 1930, stepped onto the Frisco platform decked out in a sporty safari outfit, checked into the nearby Sequoyah Hotel and enlisted the aid of several local kids to plaster the town with handbills advertising his big event. As a member of the actual expedition, along with credited leaders Sir Hubert Winstead and Daniel Swayne, Dillingham was to give a lecture at each showing.

As noted earlier, all the film’s African footage had been shot a decade and a half earlier by someone else and then pirated by producer Spitzer for Ingagi. (That someone was a British woman, Lady Grace Mackenzie, whose son eventually won a judgment against Congo Pictures for unauthorized use of the material.) So, since there was no Ingagi expedition, Sir Hubert Winstead and Daniel Swayne were not real people.

Neither, it seems, was Leon Dillingham.

Being an independent feature, without major-studio backing (although it was later picked up for booking by RKO Pictures), Ingagi made a lot of its money via roadshows, in which a studio representative would travel from town to town, carrying a copy of the movie and arranging screenings at local theaters. This worked especially well in the entertainment-starved heartland of America in the ‘30s and ‘40s, when crowds would queue up to watch just about anything that moved on a screen.

[pullquote]They could not get their money, so they said, so they did their dead level best to take it out of his hide.”[/pullquote]While this was an economical way of doing business – a small company didn’t have to come up with the amount of cash necessary to make a ton of 35mm prints – it also provided plenty of opportunities for film piracy. An unscrupulous roadshow man could, as Michael Price explains, “schlep a print over to a lab and have a copy made – a dupe – and start booking this bootlegged print himself. Ingagi probably got pirated away from the original makers more times than anyone knows.”

Now, maybe Leon Dillingham was legitimately a representative of Congo Films. But, regardless of whom he said he was, we know he hadn’t been on any Ingagi expedition, and since the film itself was created and promoted on such a bedrock of lies, what would be the harm of one more misrepresentation, of either bootlegging a print for his own gain or colluding with another film pirate to distribute one? It’s not like anybody was going to catch him.

So I want to believe that “Leon Dillingham” was a grifter, falsely identifying himself as an African explorer as he wove his way through the hinterlands, raking in money with a purloined print of Ingagi. And the main reason I want to believe he’s a poser and a crook is that he stiffed the Claremore kids he hired to pass out his handbills.

But there’s where he erred. According to an unsigned front-page story in the Sept. 4, 1930 Claremore Weekly Progress, when Dillingham tried to get out of town without paying the boys, they broached him at the depot, pelted him with rotten eggs and took off with his luggage and hat.

“They could not get their money, so they said, so they did their dead level best to take it out of his hide,” the story notes. “And in this they seem to have been successful. It is reasonable to believe that he would have fared far better if he had given each lad a small amount for the bill distribution and then left the city in peace. As it now is, he is short of his luggage and his Congo hat which he seemed to prize very much.”

Maybe, just maybe, there’s an attic in Claremore where a dusty, ancient hat still resides, a lonely and forgotten one-time trophy snatched in retribution from the head of an alleged African explorer who tried to squeeze just a little too much profit out of a stop in small-town Oklahoma.