Like clockwork each November, school children across the country wear capotains with faux buckles (although Pilgrim hats didn’t have buckles) or dress as Wampanoags in various fabrics and animal skins.

They reenact the first Thanksgiving, oft-cited as being in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1621.

However, historical and anthropological scholarship frequently spoils comfortable, repeated origin myths. Thanksgiving is no exception.

At least three feasts involving Europeans and Native Americans occurred before that famous sit-down: St. Augustine, Florida, Sept. 8, 1565; near El Paso, Texas, April 30, 1598; and Berkeley Hundred, Virginia, Dec. 4, 1619.

“Native Americans had complex reasons for allowing Europeans to settle, including a desire for trade,” says Richard Boles, Ph.D., assistant professor of early American history at Oklahoma State University. “Some Native Americans sought alliances with European colonists to gain an advantage against other Native Americans who were their longtime enemies.”

Fort Sill native Michael Gannon writes in Cross in the Sand about Spanish explorer Don Pedro Mendendez and his soldiers’ encounters with the Timucuan tribe. Their mass and feast in St. Augustine were “the first community act of religion and thanksgiving in the first permanent European settlement in the land.”

The University of Oklahoma’s Gary Anderson, Ph.D., says such gatherings were common between natives and Europeans.

“Indians loved to give ‘feasts’ and often incorporated them into religious ceremonies,” the George Lynn Cross professor of history says. “Communal societies generally place a great emphasis upon gift-giving, and gifts are often food.”

Of the thanksgiving in San Elizario, Texas, numerous historical sources report that Don Juan de Oñate, the Basque leader of an expedition headed toward New Mexico, celebrated a tortuous leg of forging El Camino Real with the Acoma tribe. They feasted on duck, geese and fish. (Oñate is also credited with bringing horses to North America.)

The Virginia thanksgiving occurred 20 miles from Jamestown, the first North American English settlement. Washingtonian magazine writes that this feast excluded native Powhatans, who were hostile because they had learned the English would take their land. By charter, Capt. John Woodliffe’s group had a thanksgiving within hours of landing and improvised with oysters and ham.

However, many native groups, especially those observing the anti-Thanksgiving National Day of Mourning, see these stories as ways of smoothing over European atrocities and genocide in North America.

Indian Country Today notes that native activists and scholars speak every November “about history as experience and handed down by their cultures” in opposition to “largely non-Natives’ … concerted effort to document ‘the true story of Thanksgiving.’”

Give Thanks to a Lady’s Magazine

Give Thanks to a Lady’s Magazine

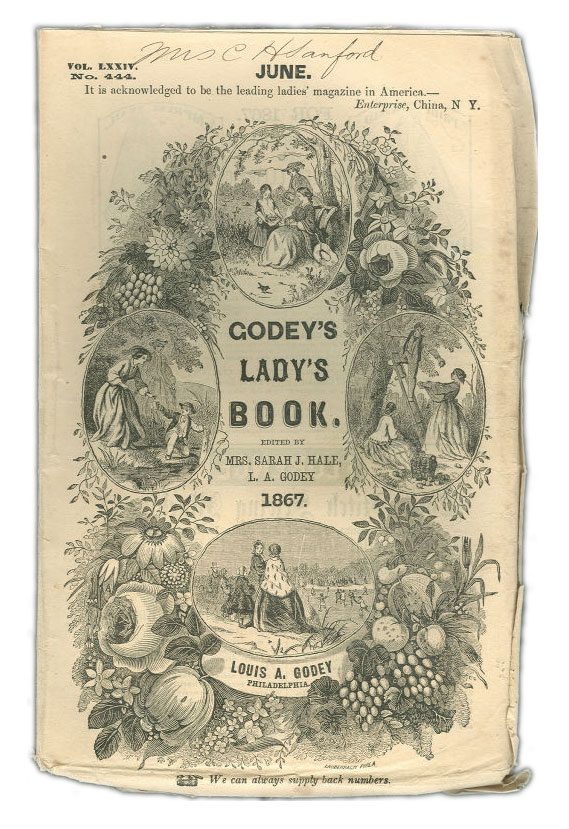

Thanksgiving did not take hold in the United States as a widely observed feast until 1836, when Sarah J. Hale, author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb” (the best-known nursery rhyme in English), became editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, an influential magazine.

For decades, Hale advocated to establish a thanksgiving as a national holiday by writing to congressional members and presidents.

She convinced Abraham Lincoln that an official thanksgiving would help to heal a nation during and after the Civil War. In 1863, he declared it a federal holiday. Thanksgiving has occurred every year since 1864 on the fourth Thursday of November.