Images courtesy John Wooley.

One of the things I’ve learned in my decades of writing about Oklahoma’s great rock ‘n’ roll-era musicians is that they are, with a couple of exceptions, not at all interested in hyping themselves or their achievements, even when those achievements are hall-of-fame caliber.

Take Tommy Crook for instance: Known among his peers to be one of the greatest guitarists the state has ever produced, right up there with the likes of Barney Kessel, Charlie Christian, Eldon Shamblin and Jesse Ed Davis. One of Crook’s early influences, Chet Atkins, said as much one evening on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, after having been exposed to Crook’s solo-guitar wizardry during a stopover at Tulsa International Airport. (Crook, at the time, had a longstanding gig at the Inkwell Club in the nearby Sheraton hotel.)[pullquote]“It all started at a Saturday morning talent contest,”[/pullquote]

Even though many musicians would wear that nationally televised endorsement like a badge, Crook doesn’t even like for people to bring it up.

“No,” he says. “That wore me out years ago.”

However, as is the case with many of his old comrades who came out of the Tulsa clubs in the ‘50s to craft what’s become known as the classic Tulsa Sound, Crook does enjoy talking about a few of the more memorable things he’s experienced in his musical life. For him, that stretches all the way back to the early years of the Eisenhower administration.

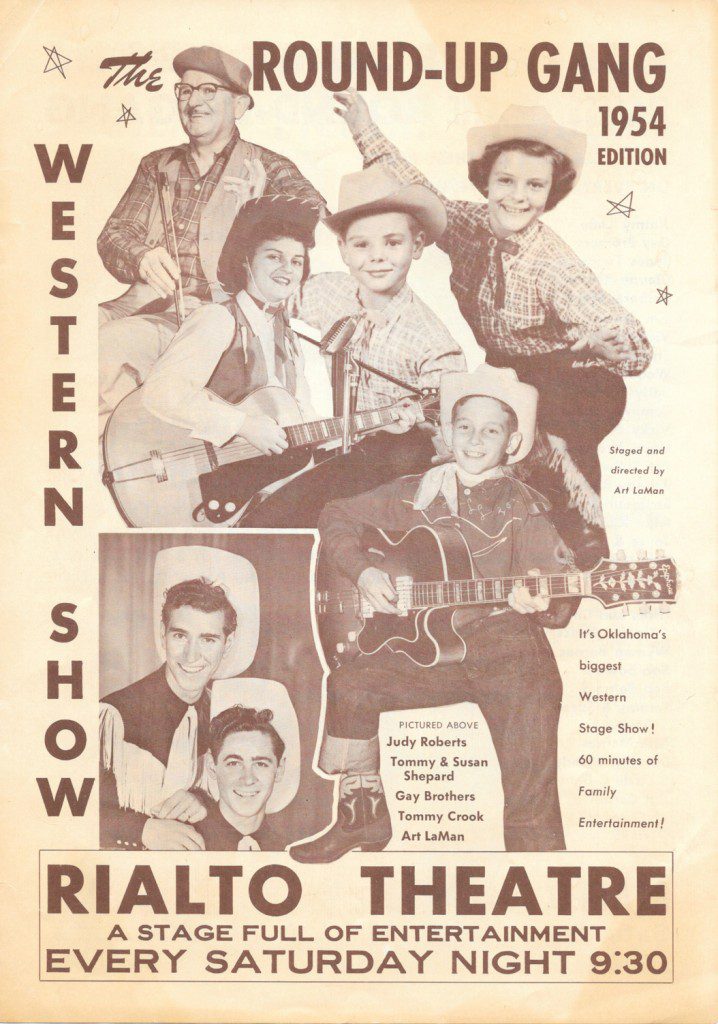

“It all started at a Saturday morning talent contest,” he recalls. “All these little movie theaters around town, especially the neighborhood theaters, would have live stuff on the stage on Saturday mornings – yo-yo contests, things like that. The Rialto, downtown on Third Street, had a talent contest, and the first prize was $10. Well, in 1953, 1954, $10 was about how much my dad brought home from work every day, after taxes.

“So we went down there. Back in those days, kids tap-danced a lot. Kids played accordion. So there were a lot of accordion players and tap dancers, and one kid by the name of Don Willis. He and I were the same age. His folks had one of the first restaurants on 11th Street, out by Wilson Junior High School, called the Chili Bowl. He was a handsome young man, and I remember he sang like an angel, with his mother accompanying him on piano. I remember what he sang, too, because I had just seen the movie, Calamity Jane. It was ‘Secret Love,’ from that movie. I’m getting chills right now just remembering it.”

As good as young Willis was, however, a cowboy-garbed Crook got the most applause from the audience, winning the top prize for his singing and guitar playing.

As good as young Willis was, however, a cowboy-garbed Crook got the most applause from the audience, winning the top prize for his singing and guitar playing.

“I remember when it was all over, and I was so proud of myself, my dad said, ‘You ought to go give the money to the kid who sang that song,’” laughs Crook. “He really was an incredible singer.”

Crook, however, was the one who landed a regular gig at the Rialto, performing live every Saturday night.

“It was just a copy of the Grand Ole Opry,” explains Crook. “About an hour show, between a double feature. The first feature was, like, at seven, then our show, and then the second feature. All for 50 cents. There’d be a dozen of us on bales of hay taking our turns and doing stuff, and [producer] Art LaMan would always bring in a headliner. Porter Wagoner, who had a big tune out, ‘Satisfied Mind,’ was one of them. I can’t remember any of the others. A lot of them were tap dancers.”

He laughs again. “This one guy came in, and he was tap-dancing, and then he jumped up on this xylophone and started playing ‘Lady of Spain’ with his feet. It was like The Ed Sullivan Show.

“They had a standing deal down there at the Rialto,” he adds. “They would give $1,000 to any kid my age who could outplay me. And there wasn’t anybody, because I had been raised up around adults who played good, and I didn’t have to wait until I was 10 or 12 to play guitar. I had one when I was 4 years old. So I’d been after that thing all my life. All my heroes – Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, my dad – they all played guitar, and that was what I wanted to do.”

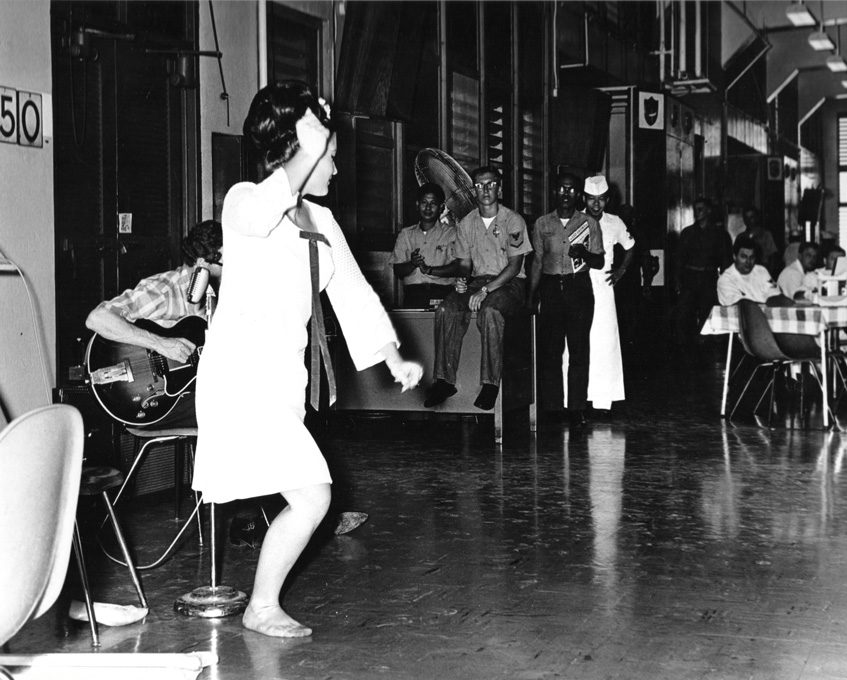

That’s what he did, too. And while he chose, for the most part, to stay close to home to play his trade, Crook did participate in some USO tours during the Vietnam era – including one with a young woman the Stillwater News-Press dubbed, in a 1967 feature story, “Oklahoma’s one-legged dynamo of energy.”

“Roberta Scott had graduated from [Tulsa’s] Will Rogers High School in 1958, the same year as David Gates and Anita Bryant,” Crook says. “She was a Miss Tulsa. Later on, she was involved in an automobile accident, nothing too serious. But when they were X-raying her, making sure there were no broken bones or anything, they found cancer in her leg and had to amputate it at her hip.

“She contacted me in the first part of 1967. She’d gotten herself an agent, and they had convinced the USO people it would be a real good thing for her to go over there to Southeast Asia, where all those hospitals were, and show the troops there could be life after losing a limb, that kind of deal. We went to Japan, Okinawa, the Philippines, Guam, Hawaii – I think we were gone six weeks, entertaining those people. At that particular time, the frug was a real popular dance, and that was her specialty.

“Traveling overseas with a one-legged dancer,” Crook muses. “How can you top that?”

Although his playing has taken him across the world, one of the places he didn’t go was southern California, which set him apart from many of his fellow Tulsa rock ‘n’ rollers in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. That’s when the exodus West began, with the likes of Leon Russell, David Gates and Jumpin’ Jack Dunham blazing the trail for their fellow musicians back home.

In Tulsa, Crook had been in David Gates and the Accents, a popular band that included Jim Karstein on drums and Carl Radle on bass. Both of them, like Gates, would find plenty of musical work in L.A. But, according to Crook, a dispute over how much Gates was paying the rest of the musicians led to Crook’s leaving the group. It happened in an Oklahoma City motel room, as they were getting ready to play a fraternity job at the University of Oklahoma.

“I went through his wallet and found the check they’d given him [for the job],” remembers Crook. “I got it out and left it lying, open, on the bed. He came out of the shower, brushing his hair with his hairbrush, and when he saw that check, he knew it was me who’d exposed him. So we started wrestling around, and he broke the handle off his hairbrush and went back in the bathroom.”

Although they played the gig together, Crook says, they didn’t talk again for decades, until Gates returned to town in 2002 to perform at Utica Square’s 50th anniversary celebration and came out to see Crook at a local venue.

Crook insists he was planning to go West with the others before that altercation, but adds that staying around town may have been a blessing.

“As it turns out, everybody was gone to California except me, so I had my pick of all the girls and all the clubs,” he says with another laugh. “I was the big fish in the pond.”