After talking with William Davis following the June 15 death of his father – Bill Davis, the Tulsa entertainment legend – I remembered a bit of sage advice attributed to author James M. Cain.

In the ’30s or ’40s, when the novelist knocked out thrillers like The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, he’d said that it was better to aim at a balloon and hit a balloon than to aim at the moon and hit a pasture.

What put me in mind of Cain’s observation was William’s telling me that Leon Russell, after coming in from the West Coast to establish a Shelter Records operation in Tulsa in the early ’70s, had offered Bill a recording contract. The catch, according to William, was that part of the deal involved Bill relocating to Southern California, where Leon would help him break into that scene.

“When he told me that, I asked him, ‘Dad, why didn’t you go?’” William says. “He said, ‘I’d rather stay in Tulsa and be a somebody than go to LA and be a nobody.’”

Tulsa, in other words, was Bill’s balloon, just as the crime novel was Cain’s. Both men aimed at their respective balloons and hit them as surely and squarely as humanly possible.

By the time Russell made him the offer, Bill was already an established Tulsa vocalist and bandleader, having been at it nearly a decade. In a column I did for this space 10 years ago, reflecting on Bill’s 70th birthday, he remembered that he had appeared with his band six nights a week for a solid 18 months at the Trade Winds Inn’s Showboat club during 1970 and ’71 – which was likely the period that Russell came to him with the proposed Shelter deal. (At the same time, Bill was working six days a week as a meat cutter in a grocery store, a trade he’d continue to ply for most of the rest of his life.)

During the interview for that column, Bill also addressed his decision to stay in his hometown.

“I’ve always said I didn’t leave because I didn’t have to,” he said. “I was able to draw good crowds and make decent money in Tulsa, so there was never any need for me to go somewhere else. And I really didn’t know if I could go play with the big boys and pull it off anyway. I’d rather stay in Bixby, wear my shorts and mow my yard. So I just stayed home and became Bill Davis.”

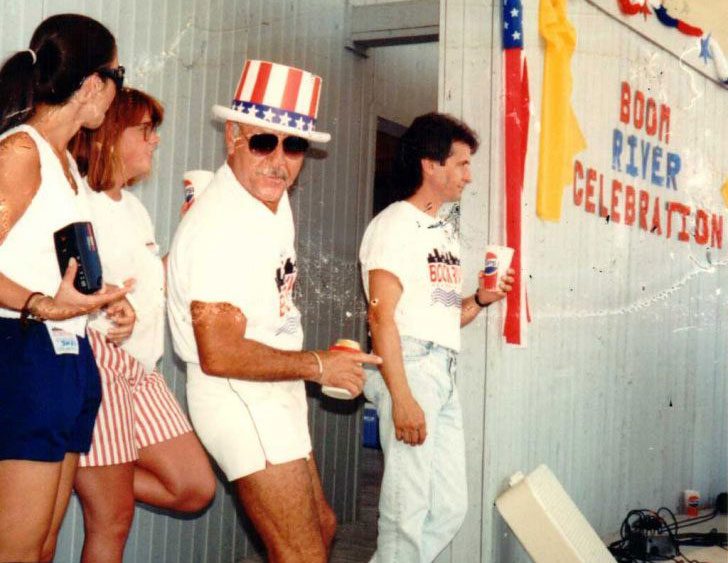

He may have stayed at home, but he spent plenty of time outside the house and away from his yard by playing live gig after live gig and appearing for a long stretch on Saturday Bandstand, the long-lived rock ’n’ roll revival radio show anchored by his friend, the music historian and musician John Henry. From the ’70s through the ’90s, anyone in the least bit attuned to Tulsa’s music scene knew who Bill Davis was. Even if you didn’t catch him on stage at an area club, you could see and hear him at festivals, outdoor summer concerts and the Tulsa State Fair, where he entertained so long and so often that he became known as the Mayor of the Midway.

That wasn’t the only nickname he picked up during his show-biz career. There were, and are, some other great white soul singers around the area – the underrated Jim Sweney comes immediately to mind – but Davis was the one known as Tulsa’s King of Blue-Eyed Soul. And radio listeners knew him as Boppin’ Billy, the King of Silly, a tag put on him by Henry.

Beginning in the mid-’80s, Davis regularly dropped by Saturday Bandstand, where he’d invariably lapse into his comedy persona, Raoul, a slightly manic hustler of indeterminate ethnic and geographic origin. He and his band – which, at that time, boasted the all-star lineup Tom Tripplehorn on guitar, Gary Cundiff on bass and David Teegarden on drums – also appeared on Henry’s Smokehouse Blues, playing live. A Valentine’s Day contest from radio station KMOD, which aired the program, even brought Davis to the homes and workplaces of female contest winners, where he delivered roses, candy and, of course, a song or two.

Through the years, working with Teegarden at the latter’s Natura Digital Studio, Davis also cut a few discs. I remember listening to one of them, back in the mid-’90s, and hearing a version of James Brown’s “Cold Sweat” on it that made me feel as though I’d grabbed a live electrical wire. Yet Davis, both funny and self-effacing about his music career, seemed never to expect much from his recorded work. (An exception was “She Can’t Do Anything Wrong,” written with Walt Richmond and recorded by Bob Seger for his platinum-selling early-’90’s disc The Fire Inside; Bill proudly told me it made both of its writers several thousand dollars each.) In an interview I did for a Sept. 27, 2001, article in the Tulsa World touting a new Davis release called Same Old Blues, he mentioned that he’d recently been to a CD release party for his friend and fellow singer Debbie Campbell and seen so many people there that he decided to downplay his own release party.

“What if I say it’s a CD release and the normal crowd shows up and we sell five?” he asked me. “So I thought I’d better go lightly on calling it that.”

In that same piece, Bill seemed to affirm the decision he’d made some 30 years before to stay in his own backyard, even though, looking back, there might have been a whiff of wistfulness in what he said.

“I’ve never toured, never been anywhere, never been to either coast, never been on a jet airplane,” he told me. “I’ve just been here and Grand Lake, occasionally slipping off to Joplin. But I’ve been steadily working since 1960, and that’s something in a small market like this. It’s something just to still want to do it.”

According to his son William, Bill still wanted to do it during the last decade of his life, but he was aware that his vocal power had ebbed, and he didn’t want to get in front of a microphone knowing he wasn’t as good as he had once been. So, by his own volition, Bill gradually edged out of the spotlight that had shone on him for so many years.

Not long after I did the piece about him for the July 2008 issue of Oklahoma Magazine, Bill sent me a note from his Bixby home and enclosed a picture of, as he wrote, “the Mayor of the Midway at age 29.”

Snapped in 1966, it shows a young man in sunglasses and slicked-back hair, sporting neither the boater-style hat nor clipped mustache that characterized his look in later years. Framed against a fuzzy background of ’60s suburban homes and cars, he wears the same expression his fans saw many times through the years – the wry smile, the confident mien of a guy who knows he’s looking good, doing well, and having fun – a man who’s already hit the very balloon he aimed for.

When I look at that photo, I think about the last lines in the note that accompanied it. They seem to form a perfect epitaph for Bill Davis.

“As the Italians say,” he wrote, “‘Death means nothing. Style is everything.’ Keep on smiling. Bill.”