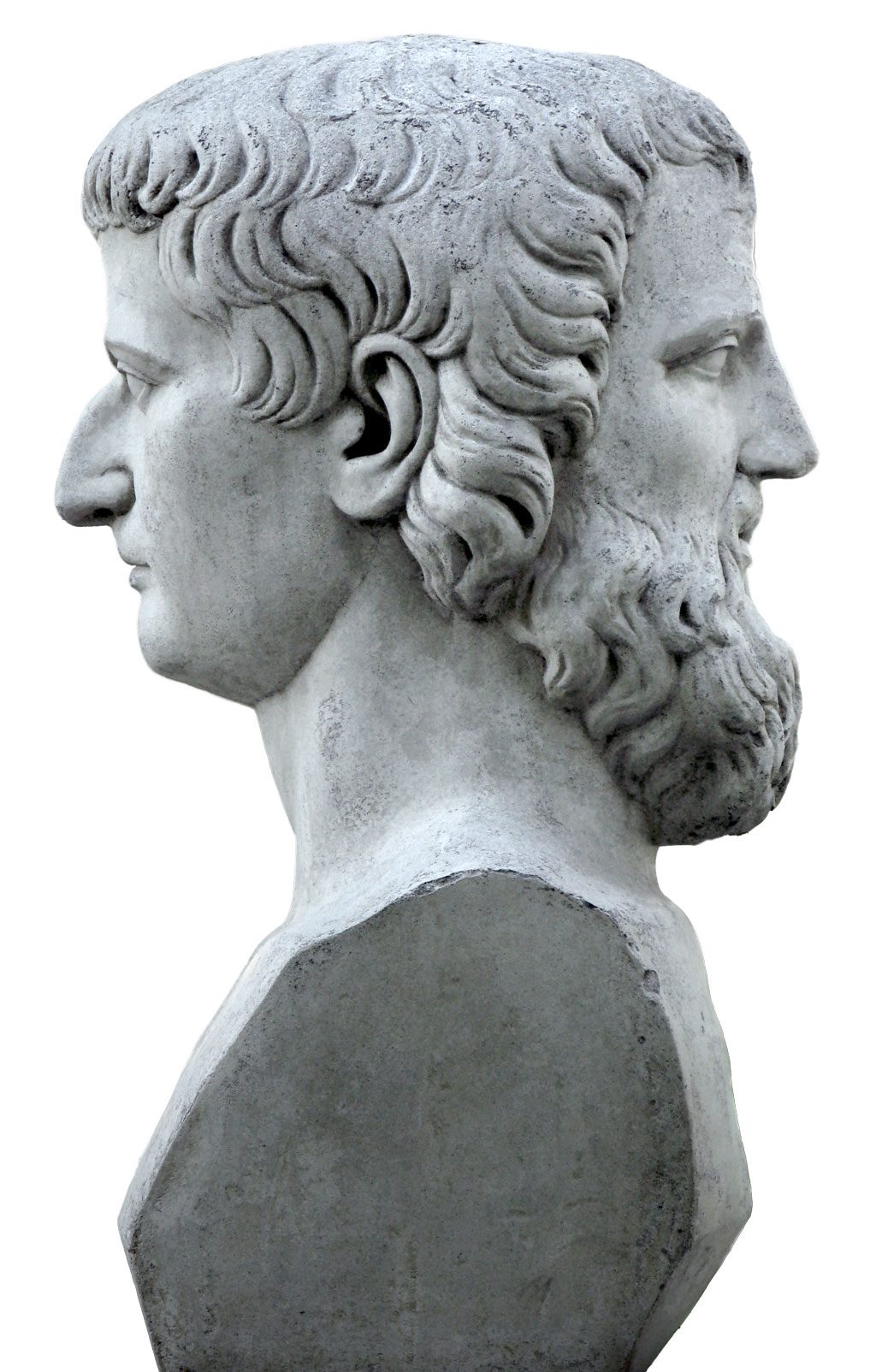

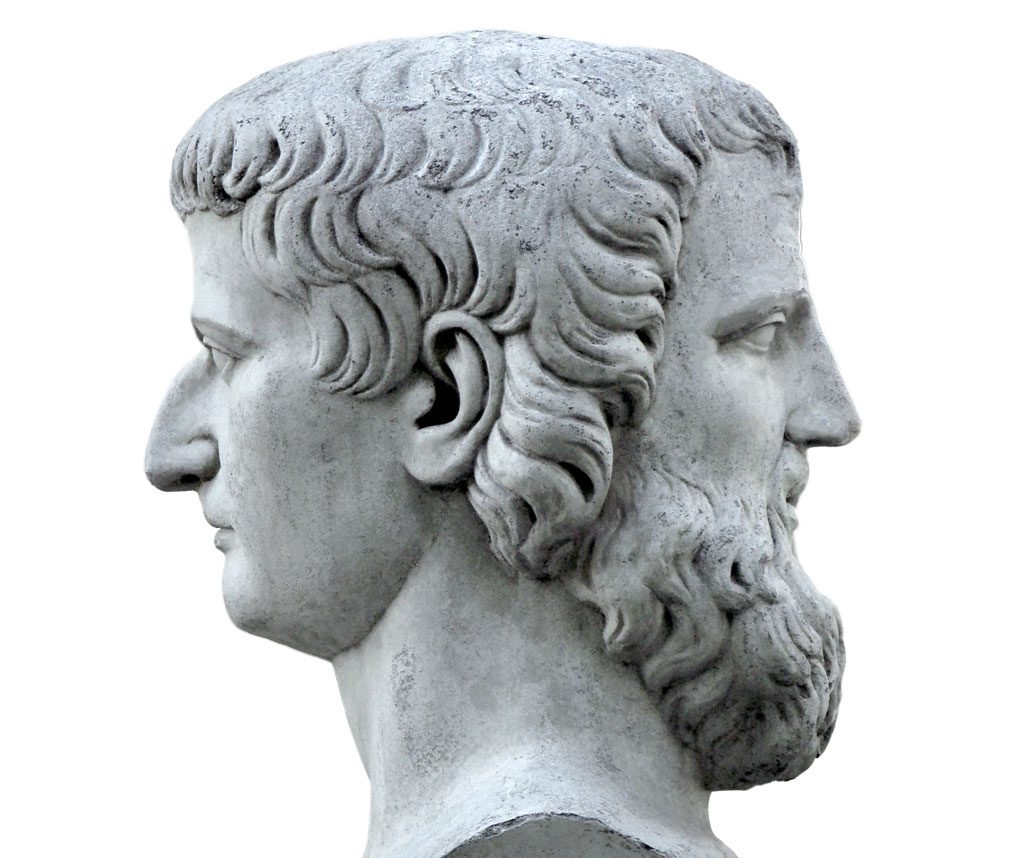

Beginnings … endings. Forward … backward. Comings … goings. These contrasts are why we have January, named after a god whose two faces and dualities embody transitions.

Janus, unique among Roman deities in that he doesn’t have an ancient Greek counterpart, gets his name from ianua, the Latin word for doorway or gate, where one can look behind or ahead, keep going or turn around, start anew or retrench.

As University of Tulsa professor Bruce MacQueen, Ph.D., notes, Janus distinctly symbolizes the past or the future, but not the present.

“If we think of time, you can’t put a beginning or ending on the present,” says MacQueen, who specializes in ancient history and languages, especially Latin and Greek. “You can’t capture the present. We have an impression of moving through it. It’s a piece of the past and the future that we call now.”

MacQueen says ancient Romans recognized the elusiveness of the present.

“The Romans were a conservative, pragmatic people, but they also realized social institutions change, so you can’t progress into the future unless you look to the past,” he says. “The Greeks would never have had a god with two faces. They would have seen a god like Janus as barbaric.”

Janus ranks as a major Roman deity (up there with Zeus) because of his omnipresence. His face was carved into marble and wood throughout the empire.

“Walking down the street, Romans would have encountered Janus constantly at every archway, every gateway,” he says. “He was in every public space.

“Because he doesn’t resemble a Greek god, Janus lacks a mythology. The Romans didn’t tell stories about him, but that was fine because he was in their everyday life.”

With Janus, MacQueen dispels the notion that Romans merely took Greek deities and renamed them.

“That couldn’t be more wrong,” he says. “Romans do appropriate a lot of the mythology, but the religions are different. You can say Jupiter is Zeus, but not really. It’s not the same. Religion and theology should remain separate when studying the ancient Greeks and Romans. It’s a mistake to equate them.”

January marks the year ahead – the face of Janus gazing at the future – but in making resolutions or plans for 2018 (or whatever year), we also look to bygone days. A desire to lose x-number of pounds or read y-number of books is based upon what has (or has not) been done.

MacQueen, also learned in neurolinguistics, illustrates this paradox with his students.

“I teach how the brain works by using Janus and asking what is now,” he says. “Now doesn’t really exist because, as soon as I say something, it’s in the past.”

So, after New Year’s revelry and excitement for the upcoming 12 months pass, our neural programming (not just our inner Roman) guides us to consider the past … just like Janus.

Not Quite Jan. 1

Not Quite Jan. 1

Ancient Romans celebrated the Festival of Janus historically around Jan. 9. His two faces were symbolic, practical and accessible. For example, a building’s weakest points are its doorways, so the Romans added this significant god of passages into frames and arches. Having a party for him just made sense.

Not Quite Jan. 1

Not Quite Jan. 1