Thanks to RSU TV – northeastern Oklahoma’s public-television station – and its senior producer-director, Bryan Crain, I was recently able to co-produce and direct a documentary that I’ve been itching to do for a long time. Called Tulsa Terrors, it’s all about the direct-to-home-video horror-movie boom of the mid-1980s and how it was ignited right in T-town. I was on the scene as a Tulsa World entertainment writer at the time, so I was lucky enough to have witnessed firsthand the start of the whole phenomenon and how it impacted home entertainment across the country and even the world.

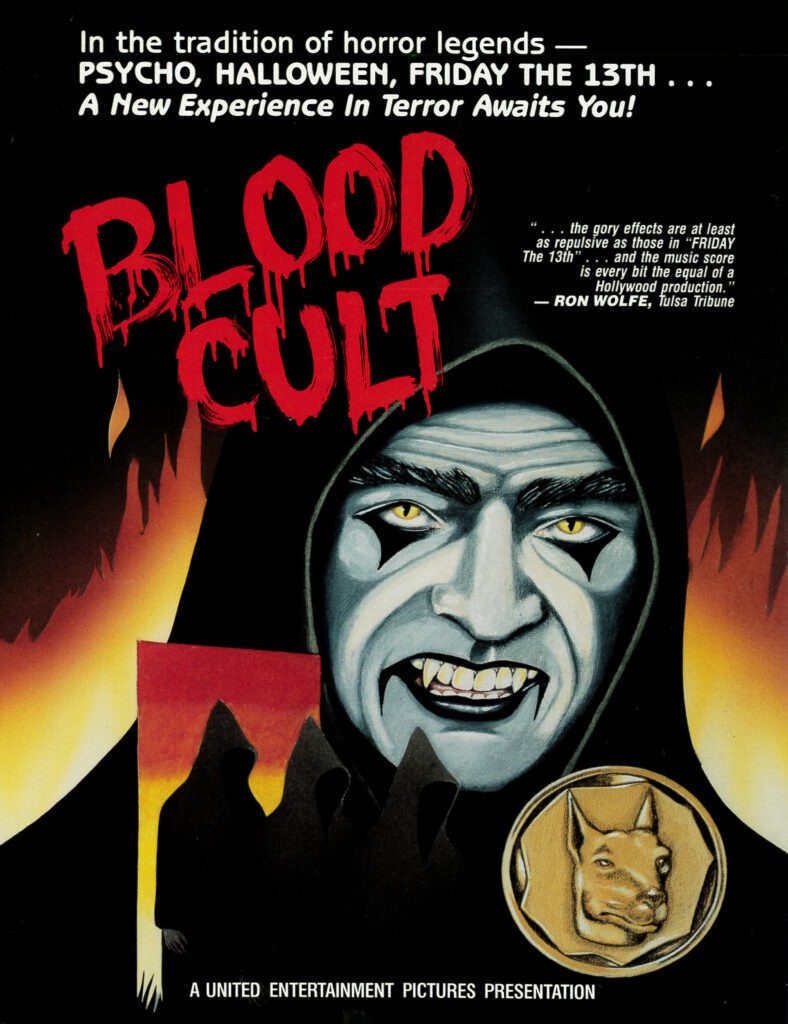

Briefly, this is what happened: A local company, United Entertainment (which is now VCI Entertainment), was doing quite well as an independent home-video distributor, shipping its product to video stores (remember those?) all over the world. Then, the head of the company, Bill Blair, got an idea. All of the movies his business handled had either been shown in theaters or on TV first, or at least had been aimed for one or both of those markets. Why couldn’t someone shoot a film directly for home video, with no aspirations for theatrical release? He just happened to have a script he’d co-written called The Sorority House Murders. So he dusted that off, connected with the husband-and-wife filmmaking team of Christopher and Linda Lewis, and their subsequent picture, Blood Cult, hit the market in 1985.

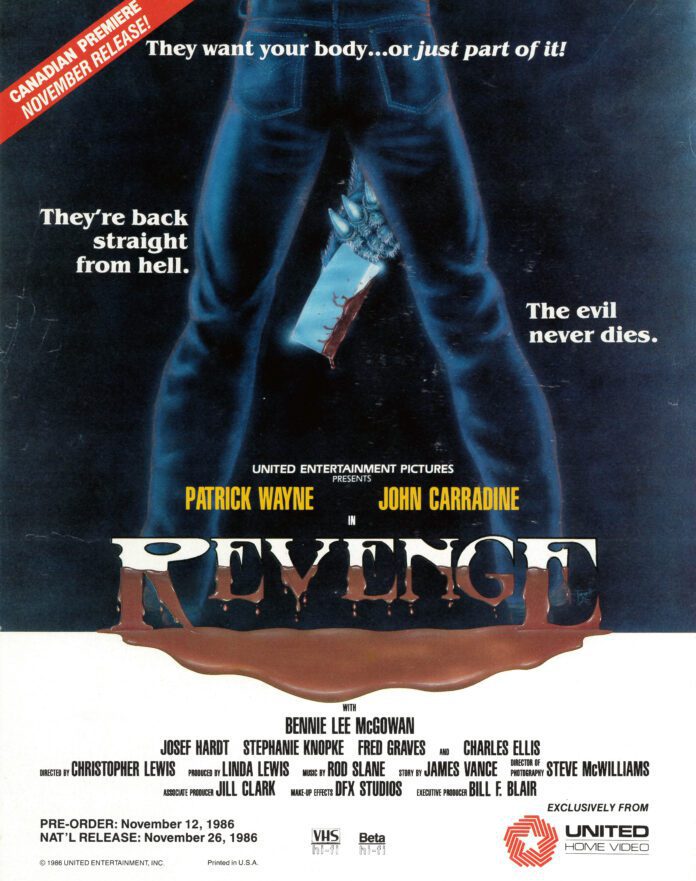

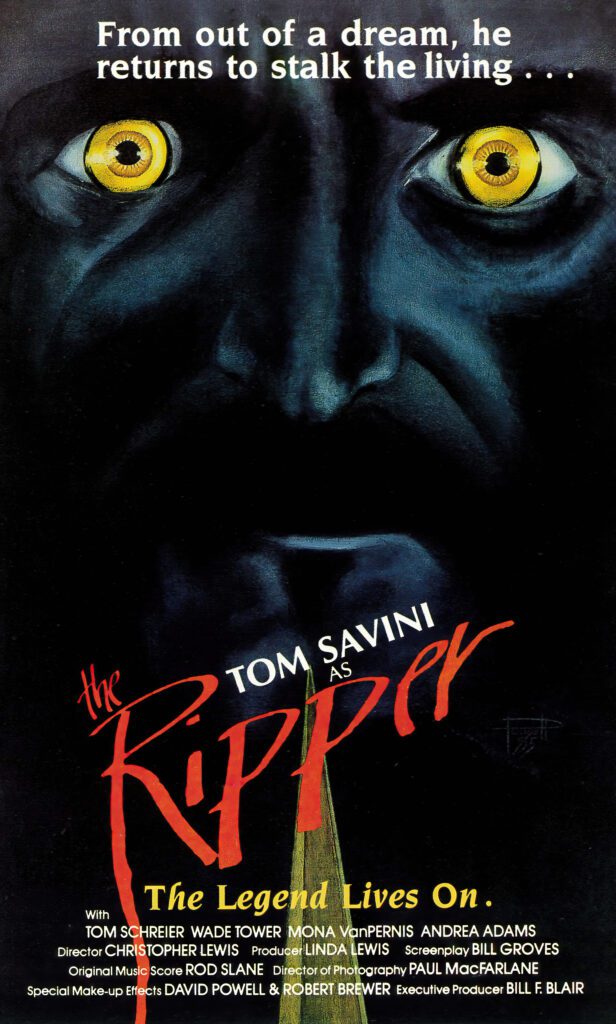

It cleaned up, too, leading to a couple more United Entertainment productions – The Ripper and Revenge – and kicking off a huge groundswell of direct-to-video pictures, as video companies all across the country stampeded toward the gold mine that Bill Blair had discovered.

Having been on the sets of all of those Tulsa features as a World writer, I was well-acquainted with how they were made and the impact they had. But what I didn’t fully realize was the fact that Bill Blair and United Entertainment/VCI had been pioneers well before Blood Cult came along.

“Dad was a visionary,” says his son, Bob Blair, who’s now VCI Entertainment’s president and CEO. “He had a lot of great ideas. Some of them came to fruition, and some had other people get hold of them and make them a reality. But he was always ahead of the curve.”

It’s hard to imagine now, but until the mid-1970s, watching a movie of your choosing at home wasn’t easy. You had to have a sound projector, and you had to rent the film on reels – which wasn’t cheap. It was definitely a niche market, but a relatively robust one.

That non-theatrical niche was served by several different film-rental firms around the country, including Tulsa’s United Films, founded with Bill Blair’s personal movie collection. Over the years, it became a family operation, with Bob’s brother Don, now retired, and their sister Rebecca, currently VCI’s office manager, coming aboard early.

“I started sweeping and mopping floors, taking the trash out, in the early ’60s, when I was eight or nine,” recalls Bob. “Eventually, I went to college and put in a couple of years, and then an opportunity came up at the company. At that time, we had branches in Albany and Denver, and the person running the Albany office left. Dad sent the lady who was manager of our film lab to Albany to run that branch, and he asked me if I wanted to manage the lab. That was about the time I got married, and I was tired of school, so I said, ‘Heck, yeah. I’ll do it.’

“That was in 1972. In 1976, Dad started a video division, and we started transferring film over to 3/4-inch Umatic [cassette] tape to service the growing cable-TV business, which was looking for movies and documentaries and things like that. He created a new company, Video Communications Inc. – VCI. Shortly thereafter, Sony came out with the Betamax recorder. For Dad, that’s when the flashing lights went off and the sirens blared and he thought, ‘Hey, I can put movies on those little cassettes and sell them to consumers.’

“So that’s what we did,” he adds. “We were one of the very first pioneers in releasing movies [on tape] to the home-entertainment market. At that point, it was really nothing more than mail-order companies, until another company bought some rights from 20th Century-Fox and turned it into a booming business.”

The boom continued as the VHS format came along to compete with, and ultimately triumph over, Betamax. Into the ‘80s, a consumer could rent movies in either format at video stores, which had popped up across the country like mushrooms after a summer rain. At its peak, the Blockbuster chain had some 9,000 locations across the world; but independent mom-and-pop stores, as well as those in smaller chains, accounted for many more.

“At one time,” says Blair, “there were probably over 50,000 rental stores, with new ones popping up every week. And they had a voracious appetite for putting movies on their shelves. It was becoming increasingly difficult for us to compete with the companies that were shelling out big advances at that time to producers, so we decided, well, let’s see if we can produce something ourselves that’s of enough quality to be successful.”

The Blairs and the Lewises opted to shoot on video, a decision influenced by a couple of things. At the time, Chris Lewis’s sister, in New York, was making hour-long soap operas in the video format. Also, VCI had recently acquired a shot-on-video movie called Copperhead. Its producers had intended to blow it up to 35mm for theatrical release, but, recalls Blair, “it just really didn’t work out that way. But it did give us the idea: ‘Why can’t we do that with something maybe a little better, a little more commercial?’ So Dad pulled out that old script, and we were fortunate to have someone like Christopher Lewis, and his wife, Linda, in town to help us out.”

(Lewis, the son of Golden Age Hollywood star Loretta Young, was at the time a news anchor for a Tulsa TV station.)

It’s always hard to pinpoint the absolute beginning of anything, and certainly there were some earlier filmmakers who might have been happy with only a home-video release, but Blood Cult was the first one to hit big on a national level.

“There were always independent producers out there making movies – some of them shot on film, some maybe on video,” Blair notes. “But it seems like their intent was always to go theatrical. We were the first to embrace the idea and say, ‘We’re going to make this strictly for the home-video market.’ And it worked. It created a pretty good stir in the business. It didn’t take long for our competitors to realize what we were doing, and they jumped on board. It became a big deal.

“I always compared it to made-for-television movies. Some of those movies were as good as anything that was being released theatrically. So why not make something just for the home-video market?”

VCI’s three home-video horror features have, over the years, become cult items, as evidenced by their upcoming reissues by the noted DVD company Vinegar Syndrome, which specializes in restored and extras-laden editions of horror and other genre pictures. Meanwhile, Blair and VCI have moved into the digital age with their catalog, which can be found at vcientertainment.com

“I guess I caught the film-addict bug from my dad,” says Blair with a chuckle. “It’s just incredibly rewarding when you create a film that people seem to enjoy, or you bring them an old classic film and make it look as good or better than it did when it was released. I’ll probably keep doing this as long as I physically can – and hopefully, there’ll be someone to come in and take my place.”