Only a select group of people had the privilege of sitting in the living room of civil rights icon and Oklahoman Clara Luper, listening to her and other black leaders plan their fight for equality.

Now visitors to the Oklahoma History Center can get an idea of the experience in the museum’s recently renovated and reopened its Realizing the Dream exhibit.

When the center opened in 2005, the exhibit was one of the three original displays.[pullquote]“My grandparents owned an entire little strip of property that included the Walker’s Hardware Store, a restaurant, a men’s clothing store and a hotel,” [/pullquote]

“It was time to give it (the exhibit) a whole new look,” says Larry O’Dell, historian at the Oklahoma History Center.

The renovated exhibit features a faithful recreation of Luper’s Oklahoma City living room, where she welcomed leaders in the black community to talk strategy. Visitors can also pick up her phone and hear recordings of Luper and other civil rights movement leaders in conversation.

A recreation of the lunch counter at Katz Drug Store – a downtown Oklahoma City business and site of Luper’s famous sit-in protest of segregation – has been updated. The center added a partial recreation of the Richard Lewis Barber Shop, originally located in Oklahoma City’s Deep Deuce neighborhood (east of downtown) and a hub within the city’s one-time all-black community for many years.

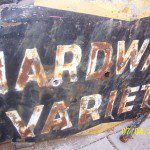

Other businesses are featured prominently in the exhibit. A large sign from Walker’s Hardware, formerly located in a strip of black-owned businesses in Deep Deuce, has been added to the display.

Oklahoma City resident Antoinette Roach’s family owned some of those businesses, and she helped save the vintage sign.

“My grandparents owned an entire little strip of property that included the Walker’s Hardware Store, a restaurant, a men’s clothing store and a hotel,” says Roach.

As Deep Deuce’s fortunes declined, Roach’s mother managed to save the Walker’s Hardware Store sign, removing it from the building in the 1970s. From there it languished in a series of garages for decades until Roach was able find a place that would restore and display the sign.

“It took us seven years to actually get the sign in a museum,” says Roach. “I’m pretty persistent.”