Before the 1973 siege at Wounded Knee, Native Americans had “to live the lie, and put their ‘Indian-ness’ away,” says Richard Ray Whitman, an Oklahoma City resident who traveled to South Dakota soon after the occupation began and stayed until a cease-fire agreement was reached.

The occupation – led by 200 Oglala Lakota and followers of the American Indian Movement – lasted from Feb. 27 to May 8. Spurred in protest of tribal president Richard Wilson, who was accused of corruption and abuse of opponents, the protest also took aim at the United States government’s failure to fulfill treaties with Native American nations.

Whitman says that when he saw the 2019 documentary From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock: A Reporter’s Journey for the first time – in which he is featured – it reminded him that the sacrifices of Native American activists have not been in vain.

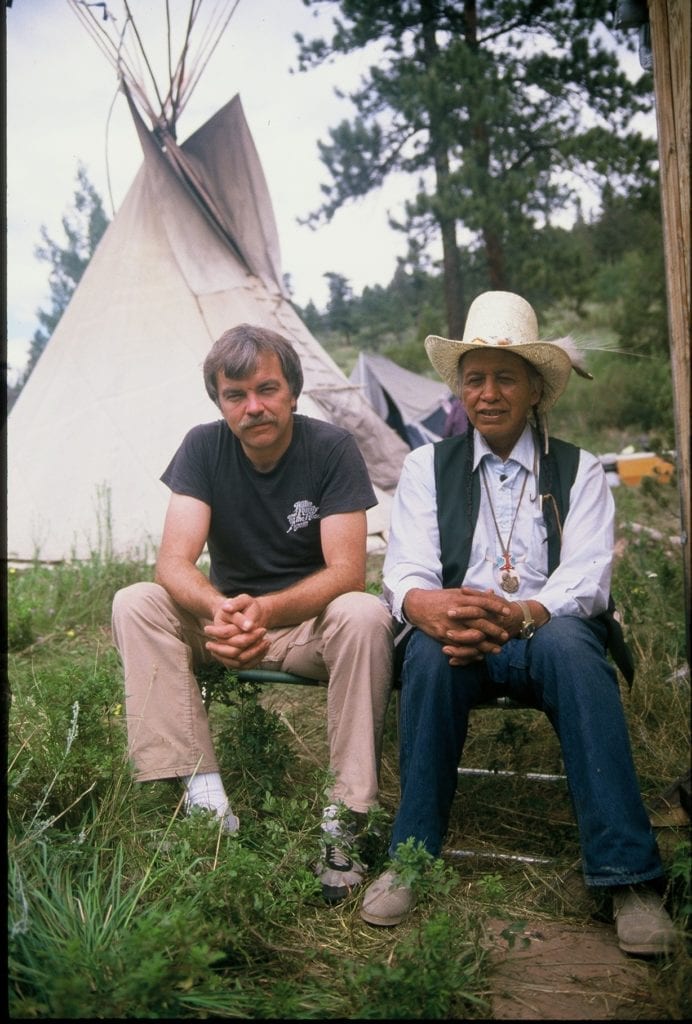

Selo Black Crow, a Lakota medicine man, figured heavily into the Wounded Knee conflict.

Photo copr. Kevin McKiernan

Kevin McKiernan stands with a wind-up movie camera at the signing of an agreement to end the Wounded Knee occupation. The agreement fell through and the occupation went on for another month. Photo courtesy Kevin McKiernan

Spurred by the American Indian Movement, the Wounded Knee occupation lasted over two months. Photo copr. Kevin McKiernan

Kevin McKiernan is pictured with a leader of the Wounded Knee occupation. Photo courtesy Kevin McKiernan

“Now, Indian people have some pride in who they are and their culture,” says Whitman, who is a member of the Yuchi tribe and grew up in Gypsy, an unincorporated community in Oklahoma’s Creek County.

“I was just a kid when Wounded Knee went down,” says artist and social activist Dana Tiger. “I remember my mom saying she wanted to go up there; my mom was fearless too.”

The Native spirit came alive at Wounded Knee, says Tiger, who is Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole.

“Now I know, as a 58-year-old woman, that they stood up for us – who were children then. I will teach my grandchild that’s what they did for us, and that’s what we do for others.”

Ken Tiger, a retired electronics technician who lives in Vallejo, Calif., grew up in Seminole and is a member of the Seminole Nation. He also appears in the documentary and says he found kinship at Wounded Knee.

“I became aware that there were other people who had similar experiences growing up, not knowing there was anything that could be done,” he says. “The more [we] got together and talked, the more [we] realized we could band together and form organizations. [We] learned to help one another.”

The film’s creator, Kevin McKiernan, says Wounded Knee brought together “all these different tribal members with different stories about discrimination and violence against activists. They all were the stories of oppression and all part of the genocide. Richard’s story had different facts, but it was the same story.”

McKiernan had moved as a teenager to Minneapolis, where the American Indian Movement was founded in response to police discrimination and poor conditions at the tenement housing where many Native Americans lived. He was in his 20s and shooting pool at a bar when he heard about the Wounded Knee occupation. He quickly decided to go and shoot photos and film.

The future Pulitzer Prize nominee says he was very much a journalism rookie when he showed up bearing a press pass from the National Public Radio affiliate in Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minn. But he possessed skills learned at the University of Oklahoma, where he earned a master’s degree and taught English from 1966 to 1968. McKiernan’s first film-making mentor, he says, was Ned Hockman, a World War II and Korean War combat photographer who helped establish the film and video studies program at OU.

“He’s kind of legendary in Oklahoma film circles,” he says of Hockman, a native of Carnegie, Okla. who died in 2009. “I became his cameraman.”

McKiernan embedded with the Wounded Knee dissidents, which resulted in his arrest as they left the village on May 8, 1973. The charges were later dropped.

The documentary also examines the aftermath of the 71-day siege, including murders on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Dana Tiger attended several screenings of the documentary, and she and McKiernan have since become friends. She had arranged for it to be shown in Muskogee on May 8, but that was postponed due to the pandemic.

Whitman, who had been an art student in California, returned to Oklahoma after also being arrested on a Wounded Knee-related complaint that never held up.

“Wounded Knee made me want to go back to Oklahoma and work with my own people, to help us heal ourselves,” says Whitman. “It will always serve as a large stepping stone in my life.”

Ken Tiger served in Vietnam as a U.S. Marine. At the Mill Valley Film Festival in California, Tiger spoke to the theater audience along with McKiernan and another Wounded Knee veteran. McKiernan asked Tiger about his decision to fight against the government he had once served.

“I was a Marine from 1963 to 1967,” Tiger replied, “but I was a Seminole from 1945 until now.”

To buy or stream the documentary, go to kevinmckiernan.com.