[dropcap]Architecture[/dropcap] matters. The forms and shapes we give our buildings – public and private – say a lot about us. Good architecture transforms a structure from a building that merely offers shelter into a thing of beauty, a work of art that touches our souls.

Floors are not just what we walk on. Walls do more than hold up roofs. And roofs do far more than keep the water off of our heads.

Oklahoma doesn’t have a Parthenon or a Versailles or a St. Peter’s Cathedral. It’s a young state, barely topping 100 years old. But it does have some gems worth seeing. It’s home to some of the best architecture of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

“Architecture matters because it’s about what we think about ourselves as a culture. We could still be living in sod houses. As far as structure, we build things that please us. We build things that wow us. We do that because it’s what we think of ourselves as a culture. That’s why it’s important. We define it and it defines us,” says Russell Baker of Manhattan Construction.

Oklahoma Magazine reached out to the experts, from architects and designers to builders and real estate experts, to survey them about the best architecture in Oklahoma. This is what they had to say.

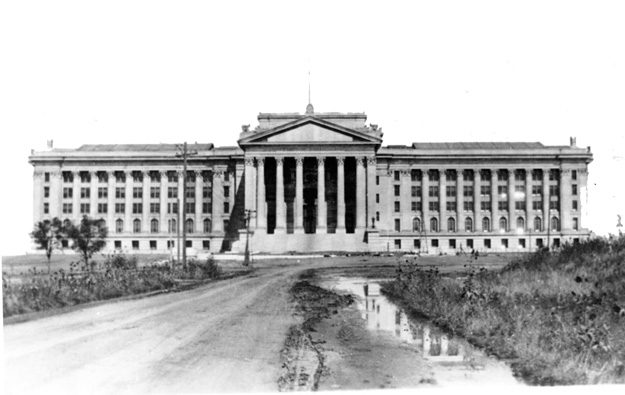

Oklahoma State Capitol

All buildings in Oklahoma are, in the grand scale of time, modern. But they’re not all built in modern styles. One building that came up in our survey is as classical as it gets – the Oklahoma State Capitol, a beautiful Greco-Roman seat of government situated in Northeast Oklahoma City.

As it does with statehouses around the nation, the Greco-Roman architecture reminds us of our governmental and legislative roots in ancient Greece and Rome, and make the building a representation in the truest sense.

“It’s more than just a building. It truly is a symbol that represents so much to the state and its people and I think that’s an important thing right now in our culture. I think it also represents a renaissance in Oklahoma. You see a lot of change in so many buildings around the state. That renaissance was symbolized with the addition of the dome in 2002. It makes a difference,” said Baker.

The original building, completed in 1917, ten years after statehood, went without a dome for almost a century – the only statehouse in the nation without one. The dome features a 22-foot reproduction of an Enoch Kelly Haney sculpture, The Guardian. A reminder of Haney’s love of his home state, the sculpture is layered with symbolism specific to Oklahoma.

Tours are available to the public.

POPS Arcadia

POPS, easily the most photographed building in Oklahoma, is more than just home to over 600 different sodas. It’s an architectural marvel. The designer, Elliot Rand, ascribes one purpose to it: to make you smile.

Aesthetically, POPS distills the best of post-war Americana, concentrating it in the form of a Route 66 gas station on steroids. A visit there leaves patrons with the feeling of traveling the open road in search of adventure and fun.

It’s equally amazing from a technical standpoint. The building is fully cantilevered, with no supporting beams. The eye can follow the roofline all the way from the front – gracefully – to the ground in the back.

“Quite honestly, I stand underneath POPS and I look at the cantilever and I’m amazed at the structure of it. While it’s not a very fancy building per se, if you ever stood underneath that and realized that the whole entire thing is cantilevered, well, that’s amazing. I love that building,” said Baker.

Interesting buildings attract interesting people. The megalithic soda pop bottle that marks the entrance of the building is a beacon for Route 66 travelers, many of them European. On any given night it’s not uncommon to hear four, five, six different languages spoken at nearby tables as tourists from around the world enjoy the Route 66 destination.

“The purpose of the building is to show that Route 66 is alive and well and moving forward. Many people think Route 66 is dead and dying and will never reappear. That’s just not the case,” said Rand.

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church – Tulsa

This spectacular 1929 example of Art Deco architecture, exploiting that discipline’s love of the vertical to evoke long-standing European Gothic cathedrals, came in at the top of everybody’s list. It is a monument to faith – and to Tulsa’s expansion during the oil boom of the 1920s.

It’s the brainchild of Adah Robinson or Bruce Goff, depending on whom you talk to, but it’s clear that both contributed significantly. Our advice: avoid the conflict. Both are luminaries of Oklahoma architecture.

Art Deco, with its inherent embrace of the technological, was an odd choice, but it works as much here for a house of faith as it does in celebrations of modernity such as the Chrysler building. And it is Art Deco at its finest through and through. Even the exit signs are Art Deco.

“It’s absolutely stunning. It’s Art Deco. It’s cut limestone. Paul Goldberger, the architecture critic for the New York Times once said it was one of his favorite buildings in the country. I think it’s a spectacular building,” said Peter Walter, a Tulsa real estate expert and an amateur historian of all things architectural in Tulsa.

Andy Kinslow of Tulsa’s KKT Architects repeated that sentiment, but offered a new angle, too. “It’s one of the best examples of Art Deco that we have around. Churches are a way to understand the history of a city. I think it represents Tulsa at a time of rapid growth,” he said.

Tours are available to the public and details can be found on the Boston Avenue Methodist Church’s official website: www.bostonavenue.org.

Citizens State Bank – Oklahoma City

For the sheer fun and bizarreness of it, nothing beats the old Citizens State Bank at 23rd and Classen in Oklahoma City. Most residents know it as the geodesic gold dome that has, over the years, housed a bank, various retail shops, a couple of bars and more than a few restaurants.

At the time of its construction in 1958, Oklahoma City architects Bailey, Bozalis, Dickinson and Roloff aspired to the truly modern and drew on the designs of Buckminster Fuller, creator of the geodesic dome. It was the fifth of its kind created in the nation.

“A purely fun piece of architecture is the Citizens State Bank. Just because [the architects] aspired to be so modern and sort of space age. I think that everybody enjoys driving past that corner,” says Randy Floyd, an Oklahoma City architect.

At its inception, the building was meant to be temporary only. After all, geodesic domes can be disassembled as easily as assembled. But it’s hung on, and was eventually added to the National Historic Registry.

Philbrook Art Museum – Tulsa

After Tulsa native Waite Phillips struck oil in the early 1920s, he banked more money than most can imagine. A portion of those funds went to the construction of Villa Philbrook, an Italian Renaissance villa on the outskirts of Tulsa. Designed by Kansas City architect Edward Delk, Philbrook Villa brought modern touches to the renaissance villa model. Phillips was so impressed he also awarded Delk with, among other things, the contract for the Philtower building in downtown Tulsa.

The grounds alone are worth the visit. They house elaborate gardens inspired by an Italian country estate designed by Giacoma Barozzi da Vignola in 1566.

After his children commenced college in 1938, Phillips excited the Tulsa community by announcing that the villa would be the home of a new art museum. The ‘wow’ factor didn’t come from the donation itself. It came from the knowledge of Tulsan art-lovers that Waite Phillips didn’t know a thing about art. And they were right. He hired a phalanx of graduate students from the finest colleges in the nation and sent them to Europe on a mission with one key weapon in their armories: blank checks. Like his west coast counterparts, such as Huntington, he knew how to fill a museum. He instructed them to bring him the best art, no expense spared. And they did. The Philbrook Museum is now one of the finest in the nation. But visitors shouldn’t overlook the architectural fineries of the villa itself while peering at the treasures on the walls.

“I like Delk’s work,” said Walter. “The Philbrook is Italian, sort of Mediterranean style, but it’s so phenomenally well done and it rings a little bit of the Southwest. He was such a talented architect and the quality of the things he built were phenomenal. There are too many things I like about it.”

The Devon Energy Center – Oklahoma City

This new entrant onto the state’s architectural scene dominates the Oklahoma City skyline, as humorously represented on the city’s new “Welcome to Downtown Oklahoma City” signs.

But, say the experts, it’s not the size of the building that matters. It’s the whole package.

“It really stands out as far as Oklahoma architecture. When you look at the level of detail, not just for the tower, but for the whole campus, it’s extremely impressive,” said Baker.

Completed in 2012, the 50-story tower is the tallest building in Oklahoma and the 43rd tallest in the U.S. It’s the northern pillar in the city’s highly ambitious – but so far successful – Core to Shore redevelopment project. The campus holds more than office space and the company’s headquarters, reaching out to the surrounding community with restaurants, an amphitheater for events and a park available to the public.

“It’s just got such a high level of architectural detail,” said Baker. “When you look at the curb details, how the building touches the ground, the way the mullions are detailed and how the glass is used, those are not details typical of what we see in Oklahoma. They’re just world-class.”

The campus is the brainchild of New Haven, Connecticut firm Pickard Chilton. Their work can be found around the globe, including the world-famous Petronas Towers in Malaysia. A public tour of the campus is available and well worth the time.

First National Bank Building – Oklahoma City

This one came in on a lot of our experts’ lists, too. At the time of its construction, in 1931, this prominent downtown Art Deco monument cost a mere $5 million. Today that’s hardly enough to pay for one floor of the Devon Energy Center.

“The First National Bank building [is] a wonderful Art Deco building and features workmanship you can’t find anymore. It’s just fabulous,” said historian Konrad Kessee.

At just under 500 feet tall, it hardly qualifies as a skyscraper these days, but it is still the third largest building in the city. Our experts raved about the workmanship on the exterior and the interior. Practiced eyes won’t miss its similarity to New York City’s Empire State Building.

As an interesting aside, the house of the original founder, E.P. Johnson, a sprawling Mediterranean product of equally amazing workmanship, still stands in the city’s Nichols Hills neighborhood, and is also worth seeing.

“It came out of an age and a style of architecture that I love, the Art Deco,” said Floyd. “It is so beautiful from a distance especially because of the stepping back of the top of the building. But when you get up close to it, it’s equally and precisely detailed.”

After the collapse of the bank in the 1980s, the building began to fall into a state of disrepair and is still in need of renovation. Occupancy rates dropped. The building’s current owner is slowly dismantling the original interior, and our experts urge architecture fans to see it now before the original workmanship is gone forever.

Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum – Oklahoma City

With taste and multiple layers of profundity, the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum commemorate the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.

Designed by Butzer Architects (also the designers of the Skydance Bridge), the memorial experience is split into two parts: a museum and a reflecting pool. While the museum, with all of its opportunities to learn about the event, the victims and the survivors, will drop your jaw, true architects will be drawn to the reflecting pool.

The grounds for the pool are anchored on the west wall by a surviving section of the Murrah Federal Building. Empty chairs representing those lost are arranged according to the location of the deceased in the building at the time of the explosion. Arches covering the reflecting mark various times during the explosion, helping visitors focus their thoughts as they move from one end of the reflection pool to the other.

Butzer Architects was selected in a design competition that included entrants from all 50 states and 23 countries. The reaction to their work has been overwhelmingly positive and it’s an experience no Oklahoman should miss.

“One of my favorites is the Oklahoma City Memorial. I think that’s pretty significant to have an architect come up with a design that is, I think pretty challenging at the very best, to symbolize what happened in Oklahoma City. I appreciate the way it evolved and came out. I think it was a pretty compelling solution for a real challenge in architecture,” said Tulsa architect Jack Arnold.

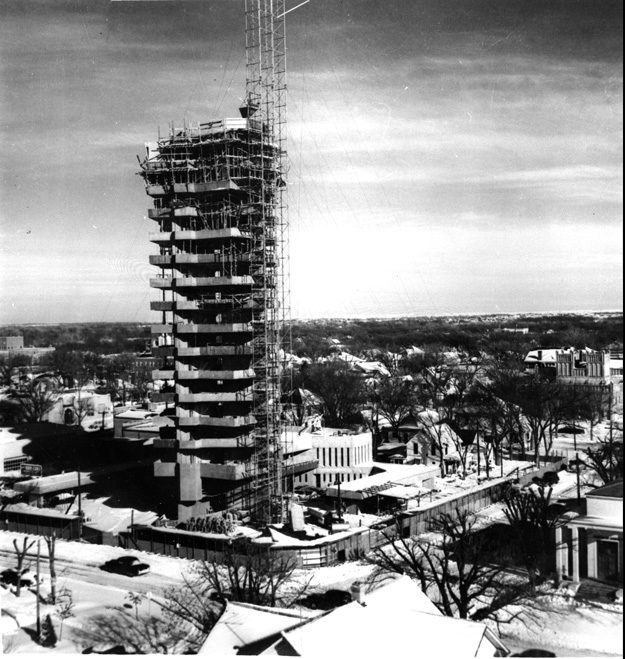

Price Tower – Bartlesville

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Price tower is a beacon of architecture and engineering to be admired. The 19-story building was completed in 1956 after being commissioned by Harold C. Price, the founder of the H.C. Price Company.

Wright’s tallest building is an example of “cantilevering,” meaning that large sections of the building are suspended without columns but instead anchored by an inner core of concrete and steel.

In 2007, the Price Tower was designated a National Historic Landmark by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior.

The Price Tower Arts Center offers tours of Wright’s only-realized skyscraper, including a stop to the restored executive office of Harold Price himself. The tours are offered Tuesdays through Thursdays from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m., Friday and Saturday at 11 a.m., 1 p.m., and 2 p.m., and Sundays at 2 p.m. Tickets are $15 for adults, $12 for seniors and $10 for children 18 and under. Because tour size is limited to 8 people, advanced reservations are highly encouraged.

Another option to catch Wright’s work now is across the state border at the Crystal Bridges Museum. The Bachman-Wilson House, a classic example of Wright’s Usonian architecture, has been assembled on the grounds of the museum. These homes were born of a utilitarian idea of simple, lower-cost (but high quality) houses that could be widely available to the middle class. Self-guided tours of the home are allowed with general admission to the museum while guided tours are offered five days a week. Find out more at www.crystalbridges.org.